Q&A: What does the EU’s new deforestation law mean for climate and biodiversity?

Multiple Authors

04.13.23Multiple Authors

13.04.2023 | 5:05pmEU policymakers are at the final stage of signing off a new law aiming to prevent the sale of products such as palm oil, coffee and chocolate if they have been produced on deforested land.

Under the proposed legislation – which passed a final European parliament vote on 19 April – companies need to prove that they did not produce certain goods on land that has been deforested since 31 December 2020.

The law has been welcomed by EU institutes and nations who say it will help to reduce the bloc’s contribution to deforestation around the world.

But others have criticised the regulation for the effects it may have on non-EU countries and small farmers.

In this article, Carbon Brief examines how the legislation will work, the issues raised by commodity producer countries such as Malaysia and how the EU assessed the law’s potential environmental impacts.

- What is the EU’s anti-deforestation law?

- Which products will be targeted by the law?

- How does the EU’s consumption of goods drive deforestation?

- How will the anti-deforestation law be implemented and enforced?

- How will the law help the EU meet its climate and biodiversity targets?

- What will the law mean for developing, biodiverse countries and how have they reacted?

- How will small businesses and farmers be impacted?

- What other issues have been raised about the law?

What is the EU’s anti-deforestation law?

The EU is a major importer of commodities that have been linked to tropical deforestation and degradation, such as palm oil from Indonesia and beef from Brazil.

In an effort to reduce the level of land being cleared to produce goods for the EU, the bloc has been working on a law to stop trading certain products that can be traced back to forest loss.

The regulation on deforestation-free products is one part of the EU’s wider Green Deal plan to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. It is replacing an existing law that aims to prevent the sale of illegally-harvested timber products.

The European parliament provisionally approved the law in December 2022.

At a plenary debate on 17 April, rapporteur on the regulation Christophe Hansen said he hopes that “other countries, such as the US” will implement similar measures. Two days later, MEPs overwhelmingly approved the deal in a final vote with 552 votes in favour, 44 against and 43 abstentions.

During the debate, politicians from Finland raised concerns about potential future difficulties for agricultural development, given that three-quarters of the country’s land is covered by forest.

Several politicians also mentioned the EU-Mercosur agreement. Anna Cavazzini, member of the Greens/European Free Alliance group, said the deforestation law cannot lead to a “bad” final Mercosur deal with insufficient safeguards for human rights and deforestation prevention. (See: What will the law mean for developing, biodiverse countries and how have they reacted?)

Hansen adds at a press conference that the law can "foster our trade relations with other economies", such as Mercosur countries incl. Brazil

— Orla Dwyer (@orladwyer_) April 19, 2023

Follows reports in recent months that a finalised EU-Mercosur deal could be back on the cards after it was provisionally approved in 2019 pic.twitter.com/zNunKwzoWe

Hansen says EU consumers can now “rest assured that they will no longer be unwittingly complicit in deforestation when they eat their bar of chocolate or enjoy a well-deserved coffee”.

The law is due to be signed off by EU ministers in the coming weeks before it officially takes effect approximately 20 days later.

However, companies will have more time to comply with the measures – large- and medium-sized organisations will have 18 months and smaller ones will have two years.

Andrea Carta, a Greenpeace EU lawyer, tells Carbon Brief that the deforestation law is “groundbreaking”.

Dr Patricia Pinho, deputy science director at the non-profit Amazon Environmental Research Institute, says it is a good idea but that it should be expanded to cover other types of ecosystem degradation. (See: Deforestation definitions and scope of ecosystems)

Once the law takes effect, companies that trade in the EU will be required to abide by a number of terms and conditions.

These rules primarily focus on ensuring that commodities and other goods were not produced on land that was deforested or degraded since 31 December 2020. Companies must also prove that their products were made in accordance with the laws in the country of production.

Countries will be ranked as posing either a low, standard or high risk of producing goods that are linked to deforestation.

Producers operating in low-risk countries will have fewer compliance requirements, whereas those in high-risk areas will be subject to extra scrutiny.

The EU says the law will be accompanied by measures such as “Forest Partnerships”, which aim to help countries protect their forests and ensure sustainable trade. The commission adds that this will be achieved while “taking into account the specific needs of local communities and Indigenous peoples”.

Carta tells Carbon Brief:

“The legislation puts companies in a proactive position. They have to put out a statement covering each supply of products and [say] ‘we take the responsibility that these products are compliant with the law’.

“All these statements are meant to be numbered and recorded in a central EU database and information system. This information system will be able to provide a complete picture of the way commodities are travelling across Europe and from where they come and if they come from countries at risk.”

Virginijus Sinkevičius, European commissioner for the environment, oceans and fisheries, has described the law as:

“The most ambitious legislative measure ever put forward by any country anywhere in the world to curb deforestation and forest degradation and to help us tackle the twin crises of global warming and biodiversity loss.”

Which products will be targeted by the law?

Research has found that a few key products and commodities are the main causes of commodity-driven deforestation. Clearing forests to create space to rear cattle caused 45m hectares of tree cover loss alone from 2001 to 2015, according to the World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Review.

The commission says it has conducted a cost-benefit analysis to decide which commodities its regulation should focus on and to find out where an EU policy intervention could be “more efficient”.

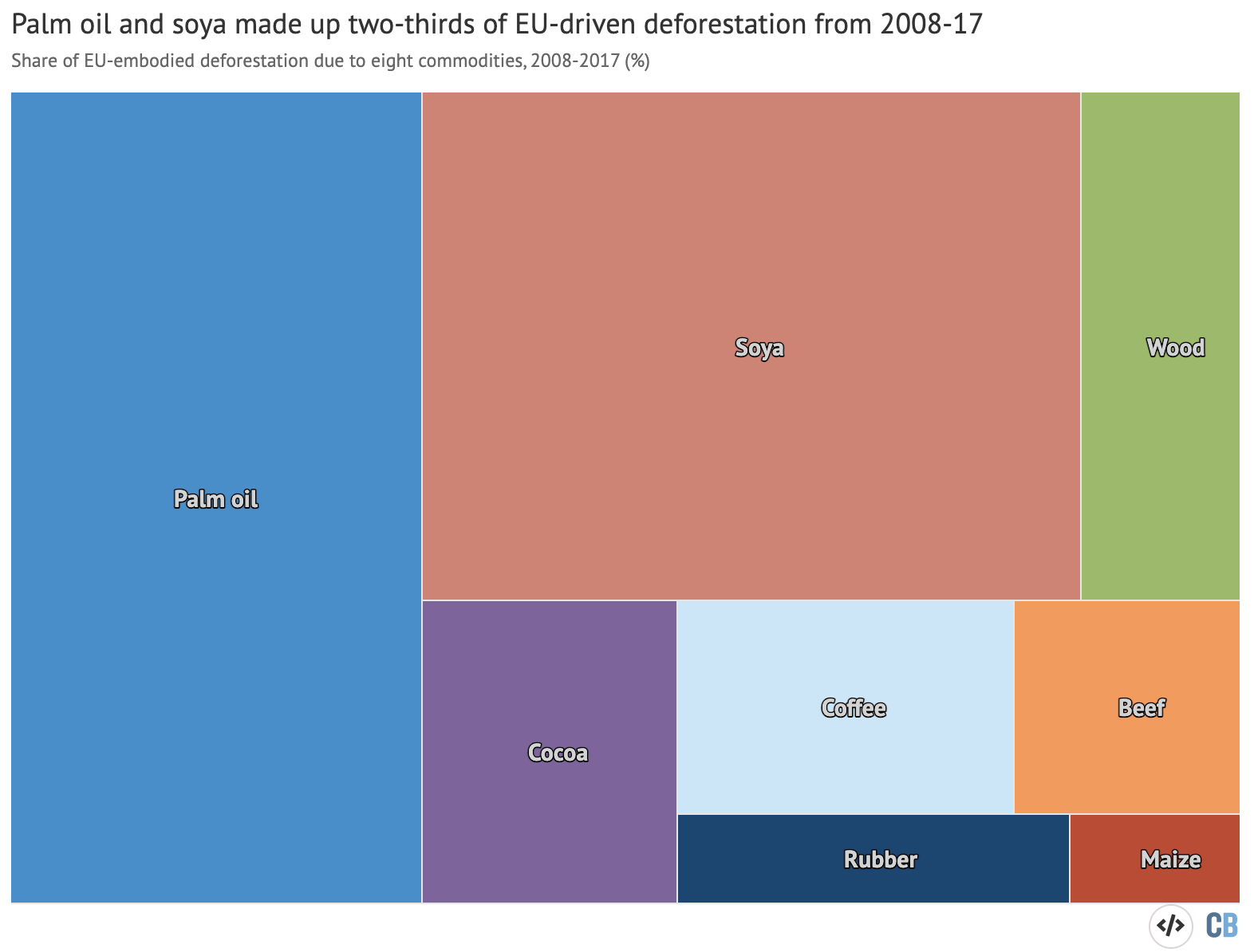

The products targeted are: palm oil, beef, coffee, cocoa, soya, wood and rubber.

The regulation also covers products derived from these commodities, such as leather, chocolate, furniture, charcoal and printed paper.

Maize was not included in the list of commodities despite being included in previous proposals. Biofuels and a wider inclusion of all livestock also did not make the cut.

Palm oil (blue) and soya (red) accounted for two-thirds of the deforestation linked to EU consumption of eight key commodities between 2008 and 2017, according to commission analysis shown in the figure below. (The proposed legislation covers the top seven of these commodities, but not maize.)

The European Commission’s impact assessment report for the law says that the EU is “among the major global consumers” of some of the products most responsible for deforestation.

Dr Anushka Rege, a postdoctoral fellow at the National University of Singapore Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions, says that the targeted commodities are significant because they are “grown in the most biodiverse places in the world” and also because “they occupy a lot of land area”. She tells Carbon Brief:

“I definitely feel like there are other crops out there that have not received as much attention, but could be potentially included in such [a] policy in the future. I specifically work on cashews, which is a problem across the tropics. But because it doesn’t cause wide-scale deforestation like, let’s say palm oil or cocoa, it has not been addressed as much.”

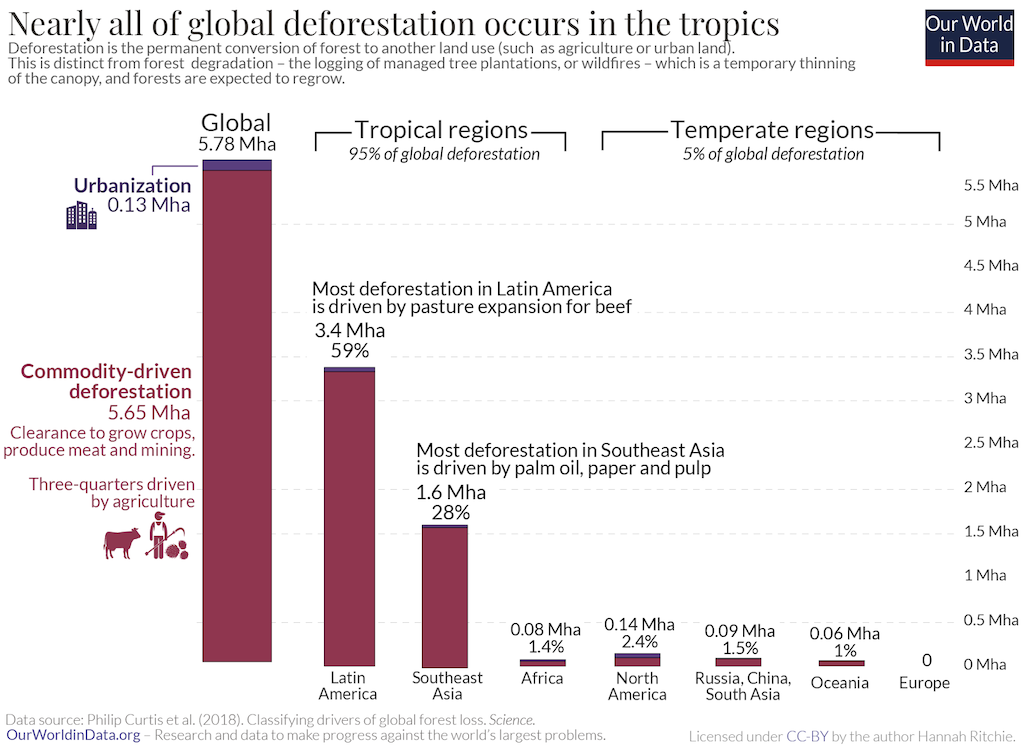

The below chart, from Our World in Data, shows how nearly all global deforestation takes place in the tropics and that the main driving forces are crops, animals and mined commodities.

Including maize and rubber in the legislation “would require a very large effort and significant financial and administrative burden”, the commission’s impact assessment report says, with “limited return” in curbing deforestation. There is a high level of trade of these commodities in the EU – around €2.8bn per year for maize and €17.6bn for rubber.

Nevertheless, rubber has remained in the proposed legislation despite not being included in earlier drafts.

A 2022 investigation by Global Witness noted that the European Tyre and Rubber Manufacturers’ Association previously said it would not be “feasible” to include rubber in the law.

But, more recently, Michelin – one of the world’s biggest tyre companies – says it supports including natural rubber in the legislation.

Carta says the proposed law is a “groundbreaking piece of legislation” and a “real gamechanger” for trade. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Imagine if you could use that same model for minerals, for metals, for plastic, for textiles, [or] to exclude forced labour, child labour, human rights violations.”

How does the EU’s consumption of goods drive deforestation?

Around 420m hectares (ha) of forest has been lost around the world as a result of deforestation since 1990, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s 2020 Global Forest Resources Assessment.

Deforestation and forest degradation are key drivers of climate change and biodiversity loss. They occur mainly due to human activities – predominantly agricultural expansion, which drives almost 90% of global deforestation, according to the UN’s FAO.

The commission says the EU is “partly responsible” for the global problem of deforestation through importing products such as soya, beef, palm oil and cocoa. It adds that the law will help to “stop a significant share of global deforestation and forest degradation”.

But the bloc “lacks specific and effective rules to reduce its contribution” to deforestation and degradation, the executive summary of the commission’s impact assessment report says.

A WWF report from April 2021 found that the EU is one of the world’s largest importers of tropical deforestation and associated emissions. This refers to the emissions or deforestation arising from goods produced in one part of the world and consumed in another.

The EU is responsible for 16% of deforestation associated with international trade – surpassed only by China, which accounts for 24%.

The same report found that the eight largest EU economies, including Germany, France, Spain and the UK (using pre-Brexit figures), accounted for 80% of the EU’s embedded deforestation through their use and consumption of “forest-risk commodities”.

The chart below shows global tropical deforestation associated with the imports of six products by country or region: palm oil, soya, cattle, cocoa, coffee and wood. (These commodities, plus rubber, are the main products targeted by the legislation.)

Rege notes that this “outsourcing” of deforestation from the EU occurs because countries in the bloc often do not have the right conditions to produce certain commodities. Palm oil, for example, grows in tropical conditions and thrives under lots of sun, rain and humidity. She adds:

“[The EU] don’t themselves have the land that’s needed or the conditions that are required to grow these crops, so outsourcing is bound to happen. Outsourcing and the demand for these products comes from the EU and a lot of the global north, that’s for sure, but demand is also driven within the region.

“For instance, India is one of the largest consumers of palm oil. That’s a demand that’s driven within Asia.”

When the regulation was provisionally approved, Anke Schulmeister-Oldenhove, senior forest policy officer at WWF-EU, said in a press release:

“As a major trading bloc, the EU will not only change the rules of the game for consumption within its borders, but will also create a big incentive for other countries fueling deforestation to change their policies.”

Stopping deforestation has been a key focus at recent global climate and biodiversity conferences.

Most recently, countries agreed on a number of new initiatives to tackle deforestation at the COP27 climate summit in Sharm el-Sheikh last year. (For more on this, read Carbon Brief’s full summary of the key outcomes for food, land and nature from COP27.)

A 2020 EU public consultation about the anti-deforestation law received around 1.2m responses – 69% of which were from EU citizens and 31% from countries outside the bloc. Respondents mostly supported legally binding rules, rather than voluntary measures, to ensure that products were deforestation-free.

How will the anti-deforestation law be implemented and enforced?

The regulation plans to limit deforestation by setting strict due diligence requirements for exporters and traders who want to sell their products within – or export their products from – the EU.

It will also entail traceability requirements, where companies will have to provide “precise geographical information” on the farmland where their products were grown or raised, so their claims can be verified for compliance using satellite imagery.

Deforestation definitions and scope of ecosystems

Defining deforestation and degradation is central to the legislation. But, at the same time, it is contentious, given differences in how countries define deforestation in their national laws, say experts.

Aida Greenbury, a sustainability expert who advises smallholders, non-profits and companies, tells Carbon Brief that there are “a lot of similarities and overlaps” between the EU’s zero deforestation law, the Global Biodiversity Framework, and national climate pledges under the Paris Agreement. However, she adds:

“There’s one consistent thing that isn’t being addressed that makes these pledges fail: there is no globally agreed definition of deforestation. What is tropical deforestation? What is legal deforestation? What about countries that don’t have a clear definition of deforestation or what ‘natural forests’ are?”

According to the FAO, what this definition does is effectively turn the spotlight on land-use change and not tree cover change. This is significant, given that in many countries, palm oil and agricultural plantations and urban parks are counted as forest cover.

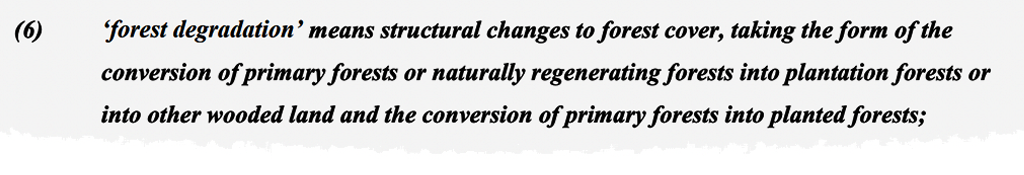

The law also expanded its definition of “forest degradation”.

The EU law reflects the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) definition of deforestation: “the conversion of forest to agricultural use, whether human-induced or not”.

This expanded definition could also impact EU countries and exporters, especially around deforestation for expanding domestic food production. Its inclusion was a “very bitter pill for the EU Council to swallow”, a parliamentary source told EurActiv when the agreement was struck in December.

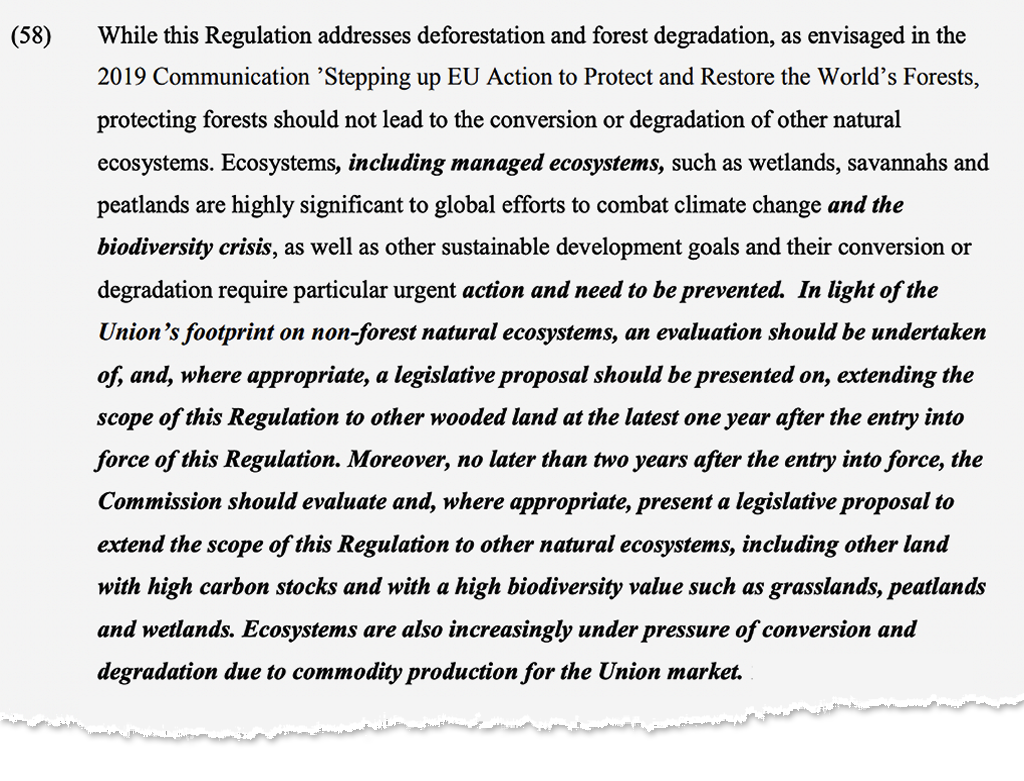

One of the biggest criticisms of the law has been the scope of the ecosystems it protects and the commodities it covers. The current law focuses only on forest ecosystems, leaving out savannahs such as Brazil’s Cerrado, which is seeing rapid deforestation rates rivalling those in the Amazon.

However, the commission will be required to review the ecosystem scope in the future. No later than a year after the law enters into force, the commission will have to determine whether to extend its safeguards to “other wooded land”. Within two years, it will make a determination about “other land with high carbon stocks and with high biodiversity value” such as grasslands, peatlands, wetlands and savannahs.

Due diligence requirements

Chief among the obligations under the law are due diligence measures that require documentation, risk assessment and risk mitigation before a company can place any of its products on the EU market.

Companies will need to spell out product descriptions, quantities and the countries and regions their products come from, along with geolocations and the time-range of production.

The law stipulates that companies will also need to provide “adequate assurances” that their products are deforestation-free and comply with “relevant legislation of the country of production”. This includes laws around human rights, trade, Indigenous rights and anti-corruption legislation.

The law’s definition of “relevant legislation” goes beyond just national laws, referring in addition to international human rights obligations, international law and, specifically, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Both UNDRIP and international human rights law contain stronger provisions on ensuring the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous peoples than some states might provide.

This wording and other safeguards throughout the text were seen as a win for Indigenous groups, although some Indigenous leaders say the law does not go far enough to protect other biomes or to verify how their rights are respected in national contexts. (See: What other issues have been raised about the law?)

Operators and traders would also need to conduct impact assessments that inform the commission of the country of production’s risk levels, the presence of forests and the prevalence of deforestation in the producer country and region.

They would need to specify “concerns” around the country and region, including corruption levels, the “prevalence of data falsification”, the lack of law enforcement, human-rights violations, armed conflict and sanctions, if any, that have been imposed by the UN Security Council or the Council of the European Union.

Risk mitigation could also include investing in and building the capacity of the company’s suppliers and smallholder farmers to comply with the law.

All of this would have to be furnished on an online portal developed by the EU no later than four years after the law comes into force.

Separately, the EU Observatory established by the commission is tasked with providing scientific evidence on deforestation, forest degradation and changes in the world’s forest cover. It is also tasked with setting up an early warning system and providing data such as land cover maps with cut-off dates, to countries, authorities, businesses and the public.

Transparency and accountability

Non-compliance with the regulation invites two kinds of actions: immediate corrective actions and penalties.

The law lists a range of corrective actions that can be imposed immediately: countries can immediately recall products, stop them from being made available in EU markets, donate them to “charitable or public interest purposes” or dispose of them. In the interim, EU member states can seize products or prevent them from being sold or traded.

It is up to individual EU member states to prescribe penalties, but these must be “effective, proportionate and dissuasive”, and “shall” include:

- Fines proportionate both to the environmental damage caused and the value of commodities, to be “gradually” increased in the case of repeated infringements, with a minimum upper cap of “at least 4%” of the operator or trader’s annual turnover in the EU member state.

- Confiscation of the products, if applicable.

- Confiscation of revenues from products.

- Temporary exclusion from public procurement for up to a year.

Compliance checks

Member states will be responsible for carrying out compliance checks of companies, as well as acting, monitoring and reporting on them, while promoting the implementation of the law with producer countries.

A digital database, dubbed the “register”, will hold all of this information. Some data will be available to the wider public to “foster transparency” in how the new law is being applied, the commission says.

The level of risk accounts for the types of commodities, the complexity of supply chains and national situations to determine the number of checks. Countries must check at least 9% of operators placing, using or exporting products from high-risk countries, as well 9% of the quantity of these products using commodities from high-risk countries. This is 1% and 3% for low- and standard-risk countries, respectively.

These measures will include on-the-ground checks of commodities and their documentation, using “any scientific and technical means” to determine whether they are deforestation-free and spot checks through authorities in producer countries – if they agree to cooperate.

The law allows EU states to reclaim the costs of all testing, storage and corrective actions from companies found to be violating the law.

Reporting

By 30 April each year, member states are expected to report to the EU Commission on all checks planned and carried out. They must include information on their results and numbers, quantities of products checked versus the total amounts imported, the kinds of non-compliance found, how these were dealt with, origin countries and costs of recovery.

By the same date, states must disclose to the public how the law was implemented in the previous year. This disclosure will include the number of checks carried out, the percentage of large companies that were inspected and the percentage of products found that were linked to deforestation.

By 30 October each year, the commission will be required to publish an EU-wide review of how the law is working, based on information states provide. This report will have to take into account the impact of the law on farmers, “in particular smallholders, Indigenous peoples and local communities”.

How will the law help the EU meet its climate and biodiversity targets?

Reducing deforestation and forest degradation lowers greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The IPCC’s special report on climate change and land estimates that 23% of global greenhouse gas emissions caused by humans between 2007 and 2016 came from agriculture, forestry and other land uses.

Without the law, the EU’s consumption and production of the goods it targets would result in 248,000ha of deforestation by 2030, according to the impact assessment – an expanse equal to the combined forest cover of Switzerland and the Netherlands.

This equates to 110m tonnes of CO2 emissions per year by 2030, the assessment says.

It estimates that 29% of this deforestation will be prevented by the end of this decade with the help of the law – resulting in at least 71,000ha of forest less affected by deforestation and forest degradation from 2030 onwards.

Additionally, this would mean a reduction of at least 31.9m tonnes of CO2 emissions each year, which would convert into annual savings of at least €3.2bn. A commission spokesperson says the CO2 savings are calculated using the “best available research”.

The price saving is calculated by placing a carbon cost of €100 on each tonne of CO2 avoided. As of 5 April, the price of carbon in the EU is €96.63 (£84.88) per tonne, according to the energy thinktank Ember.

A feasibility study undertaken for the commission and referenced in the impact assessment says that the EU’s consumption of cattle, soya and pulpwood may stagnate in future, but its consumption of other products covered by the legislation, such as palm oil, cocoa and coffee, will likely increase.

The environmental benefits, the report outlines, will vary depending on several factors, such as the regions where deforestation is reduced, the level of reduction and the affected forest type.

Forests host thousands of different tree species and provide habitats for many different species. As a result, the biodiversity benefits of the regulation are more difficult to work out.

But the impact assessment report notes that the law is set to reduce forest damage and “will therefore have a positive impact on biodiversity”.

It also says that, without further action, “deforestation will most likely continue at rates that are incompatible with many international objectives”, including the Paris Agreement.

Combating deforestation, the commission says, will go “hand in hand” with sustainable-resource incentives, which it expects will result in more intact forests, greater market opportunities for deforestation-free products and less unfair competition from unsustainable producers exporting to the EU market.

In recent years, deforestation rates have declined in some countries, such as Indonesia – a key producer of palm oil. But some parts of Indonesia continue to show increases in forest loss. Overall, global tropical deforestation remained “stubbornly high” in 2021, according to the World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch.

What will the law mean for developing, biodiverse countries and how have they reacted?

While the EU law has been hailed as progressive by some countries, it has also been criticised by others as protectionist – with the division “taking place around north-south lines”, the Third World Network reported in a briefing last year.

During a World Trade Organization’s (WTO) agriculture committee meeting on 22 November, the US and other developed countries remained silent when the EU discussed the law. Observers suggested that this was a sign that other countries were seriously considering similar legislation of their own, such as the US Forest Act.

Despite formal consultations, the current draft of the law has drawn the ire of biodiverse, developing countries – who are some of the biggest producers of commodities that will be impacted by the law.

On 29 November last year, shortly before draft regulation was provisionally approved, the governments of Indonesia and Brazil submitted a letter signed by 14 WTO member states to the president of the EU Council, the EU Commission and the Czech chair of the EU presidency. The letter was also circulated to the WTO’s committee on agriculture.

The other countries that signed the joint letter were Argentina, Colombia, Ghana, Guatemala, Ivory Coast, Honduras, Ecuador, Malaysia, Nigeria, Bolivia, Paraguay and Peru.

The group of countries expressed their regret at the EU’s move towards “a unilateral legislation instead of international engagement” to meet “shared objectives” of combating climate change and conserving forests, reflected in the Paris Agreement and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The signatories say that they were not adequately consulted on the legislation and questioned the “uncertain and discriminatory nature of the scope of products”, while pointing out “costly and impractical traceability requirements”.

The countries describe the law’s assessment and benchmarking provisions as “inherently discriminatory and punitive in nature”, and say that it is likely to give rise to “trade distortion and diplomatic tensions without benefits to the environment”.

Politico reported in January that some countries that trade with the EU are not happy with parts of the bloc’s “green ambitions”. One diplomat told the outlet that it was “easy for the EU to take a stand on deforestation in the developing world, having already deforested its own land in the past”.

Specifically, the law was labelled protectionist and discriminatory by Malaysia and Indonesia, on the back of concerns about the additional traceability burdens on smallholder farmers. In early February, Malaysia’s commodities minister Fadillah Yusof called the law “a deliberate act by Europe to block market access”, as reported in the Financial Times, while threatening to ban palm oil exports to the EU.

On 14 March this year, India submitted a paper to the WTO’s committee on trade and environment on the “emerging trend of using environmental measures as protectionist non-tariff measures”.

In the letter, seen by Carbon Brief, India claims that the new law “appear[s] to only enhance compliance burdens and generate further revenue streams for designated verification and certification agencies”, while failing to account for the “different production realities in different parts of the world”.

India’s paper submission, once again, does not separate the deforestation law from other EU measures, but sees them as a suite of unilateral measures. The letter goes on to add:

“Both carbon border measures, and the evolving laws on deforestation, reflect the growing trends towards rule-making that has an extra-territorial reach. Such measures will only burdens [sic] trade partners, especially the developing countries, with impractical, cumbersome and costly compliance obligations.”

It concludes by urging WTO members to avoid disputes and “agree to address climate change at the multilateral level”, adding that “trade measures should not undermine multilateral environmental agreements and commitments under those agreements”.

With Germany wriggling out of the EU’s moves to phase out the internal combustion engine, and the US seeking an exemption from the EU’s carbon border levy for its industry, experts tell Carbon Brief that there is no reason why developing countries would not ask the same for certain commodities or countries to be exempted.

Geneva-based trade lawyer Shantanu Singh tells Carbon Brief:

“Right from the start, EU officials have been saying at the WTO that you have to see [the deforestation law] as part of the package of measures that make up their Green Deal. There has to be a consistent, principled stance amongst the EU institutions when they’re approaching these issues. The EU has stakes in it that they’re very clear about, and any concessions that they make to other countries in their autonomous measures will problematise the whole [Green Deal], to say less about the consistency of such exemptions with WTO rules. This is just negotiation logic, the way that they’re trying to regulate trade and sustainability in their own single market.”

The EU regulation has, so far, come up in several different WTO committees that deal with agriculture, trade and environment, goods and market access. While the EU anticipates that disputes will follow the roll-out of its Green Deal policies, including carbon border measures, Singh and others point out that things at the WTO tend to move slowly.

The law is also expected to complicate the EU’s agreement with the Mercosur trade bloc of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay that has been in the works since 2000.

The EU-Mercosur deal is expected to remove duties, increase trade flows, give countries greater access to the EU and offer EU manufacturers more export opportunities. But the deal has largely been held up by deforestation and environmental concerns, particularly in the Amazon, along with French fears that markets would be hurt by a flood of produce from Latin America.

After the 19 April parliament vote passed, Christophe Hansen said the new law should “break the deadlock preventing us from deepening trade relations with countries that share our environmental values and ambitions”. He added at a press conference that the legislation gives the EU “huge leverage” to “foster” trade relations with other economies, including Mercosur.

On 11 April, EU Observer carried a comment piece titled: “Are EU deforestation rules about recolonising the Global South?” written by Arif Havas Oegroseno, Indonesia’s ambassador to Germany. In the piece, Oegroseno argues that the law “does not provide a legal basis for protection of data privacy of millions of hectares from foreign farmers, and this data is at risk of arbitrary use by the EU”.

For its part, the commission has pledged €1bn to aid the protection, restoration and sustainable management of forests in “partner countries”, such as Ghana, Indonesia, Cameroon and the Republic of the Congo.

Meanwhile, EU negotiators will also need to keep an eye on Switzerland’s Free Trade Agreement with Indonesia, which has direct concessions on palm oil specifically, based on sustainability and verification.

How will small businesses and farmers be impacted?

The EU says it has put a number of safeguards in place to ensure that the due diligence resulting from the law is manageable for companies, and particularly for smallholder farmers.

The cut-off date of December 2020, for example, was selected partly to mitigate any negative impacts for small farmers by limiting the number of people working on land that has already been deforested.

The two-year period for smaller businesses to comply with the rules is also expected to help ease the extent of the changes required.

But some non-EU countries do not agree that there will be little-to-no impact from the law.

Napolean Ningkos, the president of the Malaysia-based Sarawak Dayak Oil Palm Planters Association, tells Carbon Brief that the EU law could potentially “remove all smallholders from the entire supply chain” and that “with the current escalation of agriculture input costs, smallholders are not able to absorb any more additional cost for new compliance by EU”. He adds:

“Smallholders should be exempted from the [new law] as the best option. During my discussion with the EU ambassador in Kuala Lumpur, it is clear that [the EU] are giving us no other options and advised us to sell our products to other countries, if we failed to comply with their requirements. This is the typical neo-colonial mentality by the EU: discriminating [against] our rights to advance in socio-economic development and violating our Sarawak Indigenous smallholders legal rights over land use.”

Rege, the postdoctoral fellow at the National University of Singapore, says the regulation is a “good step” towards reducing deforestation, but she still believes it raises concerns for small farmers. She tells Carbon Brief:

“The majority of farmers in the tropics are smallholders. I feel like, while the move has been done with good intentions…it’s going to be really hard in practice to make sure that the transparency and the traceability of the product remains intact.

“I feel like farmers need to be consulted at every step of the way. Farmers and middlemen, because a lot of this is affecting their livelihoods and I feel like what they have to say would really affect the policy in the longer run.”

Michalis Rokas, the EU ambassador to Malaysia, met with Malaysian palm oil smallholder representatives in March to receive a petition about the anti-deforestation regulation.

Rokas said on Twitter that he “listened carefully to their concerns” and would pass them on to European headquarters. He added that, as Malaysia already has ways to ensure deforestation does not occur, “we do not expect any extra costs for smallholders”.

The EU and member states “stand ready to support” Malaysian palm oil smallholders “in their journey towards sustainability”, he added.

Responding to criticisms about the legislation, a European Commission spokesperson tells Carbon Brief:

“The EU deforestation regulation does not create obligations for other countries. It regulates market access through obligations for EU operators and traders.”

In 2020, the commission set up a “multi-stakeholder platform on protecting and restoring the world’s forests”. This aims to involve stakeholders, researchers and other countries in the EU’s legislative process.

The spokesperson says that people participated in developing the legislation through “dedicated workshops, updates given by the commission and requests for feedback and inputs”.

They note that “the same will be done for implementation”, adding:

“The multi-stakeholder platform will become an essential forum to consult partner countries. The commission has also intensively engaged in bilateral meetings and relevant multilateral fora to explain its proposal both before and after its adoption, including with partner countries as well as with relevant industries.”

The commission also says it will engage with countries at high risk of deforestation to help them reduce risk levels.

However, Indonesian independent smallholders say they are already struggling to comply with legal measures, good agricultural practices, environmental management and transparency and traceability requirements, according to a survey covered by Mongabay.

Nonetheless, an Indonesian smallholder palm oil farmer organisation called Serikat Petani Kelapa Sawit (SPKS), which translates to Palm Oil Farmers Union, said in a press release that the regulation “could be a great opportunity” to benefit from the EU market by providing deforestation-free products.

The secretary general of the union, Mansuetus Darto, added that Indonesian palm oil farmers need the EU’s support and assistance to properly abide by the regulation.

Greenbury, who advises SPKS, told Carbon Brief that geo-referencing and traceability are “actually not that difficult, despite what other industry spokespeople claim”. She added:

“Smallholders in Indonesia – including SPKS members – already have traceability systems in place. But they need support to strengthen their institutions, their cooperatives, and improve their skills, such as via training to manage traceability data, because there will be a lot of data. For just one single commodity like palm oil, for example, how are we going to trace it back? It is mainly the responsibility of the buyers of the produce to start pitching in to support this.”

She points out that ending deforestation and restoration must go hand-in-hand and that “big consumption money” should go towards supporting restoration, “especially given the [global] north’s historical background in colonialism”.

The law is expected to have other effects. EU states with large livestock populations may be affected by increased feed prices once the regulation is in place, the commission’s impact assessment report says.

Soya, much of which is imported from countries such as Argentina, Brazil and the US, is primarily used for animal feed in the EU. The impact assessment says that more soya could be imported from the US as a result of the legislation.

What other issues have been raised about the law?

Indigenous peoples’ organisations have criticised the scope of the proposed regulation, saying it should cover more than just forest ecosystems.

In January last year, 22 Indigenous organisations from 33 countries, supported by 169 human rights and environmental groups, wrote an open letter to the commission demanding that the law explicitly require companies to uphold international law and standards on community tenure rights, consultation and consent, as well as to “respect the right of forest defenders to conduct their work without retaliation”.

Furthermore, a coalition of Indigenous and local community groups in 24 tropical countries says the EU has put their fate “in the hands of the very governments that have violated our rights, criminalised our leaders and allowed an invasion of our territories”, putting vital ecosystems at risk.

The Global Alliance of Territorial Communities adds that the proposed agreement is “failing to protect our rights, including our land rights”.

The regulation text acknowledges that environmental human rights defenders are “most likely to be a target of persecution and lethal attacks” that “disproportionately affect Indigenous peoples”.

The proposed law “ensured that the rights of Indigenous peoples, our first allies in fighting deforestation, are effectively protected,” rapporteur on the regulation Christophe Hansen said in a statement in December.

Meanwhile, ecosystem issues remain. Pinho, from the non-profit Amazon Environmental Research Institute, believes the Cerrado in eastern Brazil, the world’s largest savannah, should be included under the remit of the regulation. Pinho tells Carbon Brief:

“We’re absolutely not against the legislation, and by no means against the need of [stopping] illegal deforestation in the biome of the Amazon.

“They say that in a year they will revise it, but a year can mean a lot in terms of deforestation, or to the legal deforestation that large properties can do.”

Pinho also discusses a risk of “leakage” in importing products or commodities grown on deforested land to China instead, where trade rules are not as strict around deforestation.

This leakage risk is one example of how the legislation could “backfire” against its “good intentions”, she says, adding:

“The weakest point of this legislation has been those aspects related to this leakage effect and the indirect emissions associated and not incorporating Cerrado. Also for having a Chinese market that dominates the transactions or the trade in Cerrado regions.”

Research shows that almost 70% of beef from Brazil exported to China came from the Amazon and Cerrado regions in 2017, according to data pulled together by Trase. Pinho says:

“In a time when we are talking about loss and damage…The European Union per se acknowledges the historical influence of global greenhouse gas emissions associated with their economic development.

“They’re acknowledging this guilt and blame, but they are not doing enough. It’s still trying to get as much as they want in a short period of time.”

-

Q&A: What does the EU’s new deforestation law mean for climate and biodiversity?