Climate resilience: Is the UK ready for the impacts of global warming?

Multiple Authors

03.13.23Multiple Authors

13.03.2023 | 7:16amEvery area of UK society will feel the effects of climate change and, as global emissions continue to rise, preparing for life in a warmer world is crucial.

This is the focus of the UK Climate Resilience Programme, which is a government-backed initiative with the goal of understanding the risks the nation faces and helping people to adapt accordingly.

Last week, researchers involved with the programme gathered at the Wellcome Collection in London to present and discuss their findings. They ranged from assessments of elderly people overheating in care homes through to building community-run water storage.

Carbon Brief attended the conference and has captured the key points from the research projects, which are now intended to help businesses and policymakers adapt to climate change.

- What is the UK Climate Resilience Programme?

- What are the latest findings for climate hazards in the UK?

- What are the tools that can help the UK adapt to climate change?

- ‘Gaps’ and future steps

What is the UK Climate Resilience Programme?

The UK Climate Resilience Programme is a £19m scientific research project running from late 2018 to early 2023. It is jointly led by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Met Office.

According to the programme’s website, its aim is to fund research “to help understand how to quantify the risks from climate change and build climate resilience for the UK”. This research should produce “usable outputs” to “directly support decision-making” by government, local authorities, communities and other stakeholders.

The two-day event held from 8-9 March at the Wellcome Collection in London was the programme’s final conference. It gave researchers and stakeholders the chance to present their findings, as well as reflect on what could have been done differently – and what should happen next.

Speaking at the conference’s opening, Prof Stephen Belcher, chief scientist at the Met Office, said the programme also aimed to bolster the importance of climate adaptation in the UK, which is sometimes referred to as a “cinderella topic” when compared to efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

He told delegates that “keeping adaptation in everyone’s minds as well as mitigation is a struggle”.

Also at the start of the conference, Prof Gideon Henderson, chief scientific adviser at the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), said the research findings would underpin the country’s third National Adaptation Programme, which is due to be published this summer.

What are the latest findings for climate hazards in the UK?

Storms

Understanding how UK storms could change as temperatures rise will be key for helping communities prepare for climate change.

On the conference’s first day, Dr Colin Manning, a research associate at Newcastle University, ran through the findings of the Stormy-Weather project, which aims to understand how UK storms are changing and what they might look like in the future.

One finding from the project is that storms in the UK could become more slow-moving in future, giving them longer to unleash rainfall over towns and cities, he explained. This could have implications for flood risk.

Manning also presented the findings of his preliminary research examining how climate change could affect the occurrence of windstorms and “sting jets” in the UK. (A sting jet is a small area of very intense winds – often 100mph or more – that can sometimes form during a storm.)

His research suggests that, under a very high greenhouse gas scenario, windstorms and sting jets could become more frequent and intense across the UK by 2070.

Flooding and drought

One of the biggest climate hazards facing the UK is flooding. Dr Pete Robins, an oceanographer at Bangor University, discussed one aspect of this in his talk on the Sensitivity of Estuaries to Climate Hazards (SEARCH) project.

The 20 million people who live near estuaries in the UK are vulnerable to “compound flooding” as high rainfall combines with storm surges from the sea. Robins and his colleagues have assessed how common these events are in Great Britain.

For the Dyfi estuary in Wales, they have also shown that the number of compound flooding events are set to increase in the future as the climate changes.

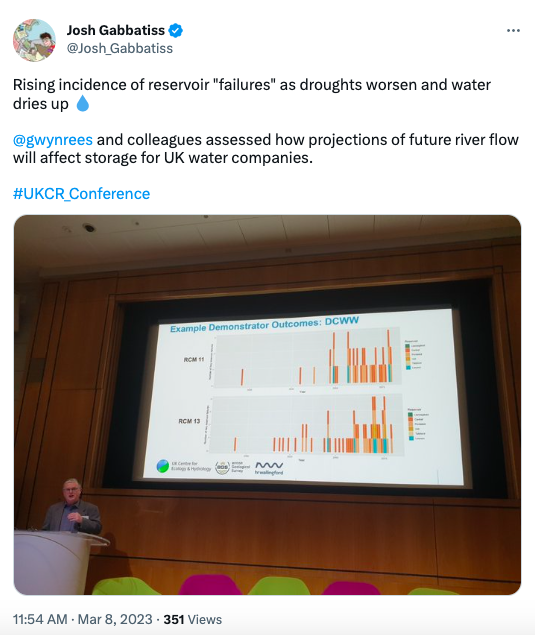

At the other end of the water spectrum, Dr Gwyn Rees, a senior research manager at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, introduced his team’s Enhanced future Flows and Groundwater (eFLaG) project. They have produced projections of drought risk to help the water sector prepare for a future of more prolonged and severe droughts.

Overheating in schools, prisons and care homes

Several of the talks explored the issue of overheating in UK buildings as temperatures continue to rise.

On the first day of the conference, Prof Michael Davies, a researcher at University College London, presented the preliminary findings of Climacare, a project examining the impact of overheating on UK care homes.

The project aimed to explore the impact of heat on care homes through temperature measurements, physiological assessments and by producing projections for how impacts may worsen in the future.

However, much of the research was disrupted by the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic, Davies told the conference, which prevented the team from having access to carehomes for much of the study period.

Despite this, Davies’ team were in September 2022 finally able to access care homes to begin taking temperature measurements. Preliminary results show that around half of bedrooms in care homes were routinely overheating at that time.

Elsewhere, Dr Laura Dawkins at the Met Office explained how high-resolution maps of hot day increases across the UK could be used to identify schools that are particularly at risk from overheating.

She added that a similar approach could be used to identify prisons that are particularly at risk from overheating.

What are the tools that can help the UK adapt to climate change?

New climate information

Many of the talks focused on “climate services”. These were defined by Murray Dale from JBA Consulting as involving “the production, translation, transfer and use of climate knowledge and information in climate-informed decision making”.

Climate services could be an important tool for adaptation because they can provide people with the relevant information to prepare for climate change.

Some of the speakers were involved in developing this “knowledge and information”. For example, Victoria Ramsey, a senior climate scientist at the Met Office, explained her team’s work developing “city packs” to help city councils develop informed responses to climate change.

Dale himself has been developing a set of standards to ensure better quality control amid the “wild west” of climate services.

“In the UK there are probably thousands, internationally there may be millions…Who knows how good they are, how effective they are,” he said.

Meanwhile, Louise Wilson and Dr Natalie Garrett from the Met Office laid out their recommendations for a UK National Framework for Climate Services. Wilson said they wanted to provide a “driving force” for the nation’s climate services community and help ensure that “adaptation action actually does get done”.

UK ‘SSPs’

“Shared socioeconomic pathways” (SSPs) are tools used by researchers to explore how society will change in the future. This can help them to answer important questions about climate change.

As there were no UK-specific versions of SSPs available to complement the UKCP18 climate projections, Ornella Dellaccio, from the consultancy Cambridge Econometrics, and her collaborators set out to develop some.

The outcomes of this project include a set of “narratives” for the five different SSPs that have been refined for a UK context.

For example, the “sustainability” pathway results in a “more egalitarian” society after new legislation “stimulates green transitions”. On the other hand, the“fossil-fuelled development” pathway includes scaled-up public investment in fracking, which “heavily contributes to the removal of the north-south divide” in England.

Community and cultural approaches

Several of the projects involved working closely with local communities to support adaptation.

This included “co-producing green infrastructure”, in the case of the project led by Dr Liz Sharp, a professor at the University of Sheffield. Her team helped people in Hull to design and build an “alternative reservoir” system of rain tanks and gardens.

Dr Alice Harvey-Fishenden, a historical geographer at the University of Liverpool, worked with communities in Cumbria, Staffordhire and the Outer Hebrides to understand how they have historically experienced and adapted to climate change. She said:

“People don’t think they know anything about climate…which is obviously untrue because as soon as you get them talking they have loads of memories of past extremes, how affected certain places are. They are the experts in their local area.”

Christopher Walsh, a PhD researcher at the University of Manchester, discussed his research into the climate hazards facing churches and developing guidance to make them more resilient.

He noted that the Church of England owns around 16,000 buildings, one-third of which are considered at risk for a variety of reasons, including flooding and overheating.

‘Gaps’ and future steps

As the conference came towards the end of the programme, many of the delegates took the opportunity to take stock on its achievements and potential shortcomings, as well as possible next steps.

One “issue” identified by speaker Prof Nigel Arnell, a climate scientist at the University of Reading, was the programme’s somewhat narrow approach to projecting changes to climate hazards in the UK.

To understand how climate hazards could change in the future, much of the research funded by the programme made use of the Met Office’s UK Climate Projections 2018 (UKCP18) local 2.2km data.

These projections – a subset of the wider UKCP18 set of products – contain high-resolution information on how temperatures, rainfall, cloud cover and humidity could change in the coming decades, as well as forecasts for how far sea levels around the UK could rise.

The comprehensive nature of the projections have allowed researchers to examine changes to climate hazards in finer detail than ever before. (For more detail, see the Carbon Brief guest post written by Met Office scientists and other researchers in 2021.)

However, due to computing constraints, the high-resolution projections have been based around just one main scenario: where future greenhouse gas emissions are very high (“RCP8.5”). The team then used scaling techniques to assess the impacts at lower levels of warming. (See Carbon Brief’s UKCP18 explainer for more details. It is worth noting that the wider package of projections provided by UKCP18 uses a range of emissions pathways and levels of global warming.)

Arnell pointed out that the inclusion of this very high emissions scenario does not allow for easy comparisons of climate hazards at different degrees of global warming, which could have been useful to policymakers and other stakeholders making decisions about adaptation.

Climate change affects people in different ways, with women, people on low incomes and minority communities often facing additional burdens. In the UK, there is evidence that socially deprived communities face elevated flood and heat risk, for example.

While several speakers mentioned social inequalities across the conference, none of the projects discussed focused specifically on this aspect of climate resilience and adaptation.

Elsewhere during the conference, several speakers and audience members raised concerns that the stakeholders making decisions about climate adaptation – ranging from community leaders to local government employees – were not involved with the programme early enough.

If a similar programme were to go ahead in future, stakeholders should be involved in its inception to ensure the information produced is useful and relevant to them, several delegates argued.

Elsewhere, others raised concerns that the results of the programme may not necessarily be translated into action by the UK government.

A keynote speech on the second day was given by Prof Swenja Surminski, an adaptation researcher in the Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and member of the Climate Change Committee’s (CCC) Adaptation Committee.

Referencing her own work advising the government with the CCC, she made it clear that the UK government’s action on adaptation action still contained “significant gaps”.

Surminski also highlighted the important role that research could play in bringing stakeholders together and informing public and private institutions as they act on climate adaptation. She said “lock-in” decisions about infrastructure need to be made “basically today”.

“That’s really important, and I think that research can play a huge part in highlighting how these decisions put us on the wrong pathways.”

Update: This article was updated on 15/03/2023 to clarify that the 2.2km high-resolution projections are a subset of the wider UKCP18 package of products.