Tipping points: How could they shape the world’s response to climate change?

Multiple Authors

09.16.22Multiple Authors

16.09.2022 | 2:27pmResearchers, economists and civil society representatives gathered in Exeter this week to discuss the prospect of “tipping points” in a warming world.

Over three days at the University of Exeter, the conference aimed to both improve “warnings of the imminent risks of catastrophic climate tipping points” and accelerate “positive tipping points” to trigger “rapid and transformative solutions” to climate change.

The conference followed closely after a major new review study – published last week in Science and covered by Carbon Brief – which warns that there is a “significant likelihood” of multiple tipping points being crossed if global warming exceeds 1.5C.

Opening the conference, Prof Tim Lenton, director of the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute, said:

”We convened this meeting because we feel strongly that human activities are pushing the Earth system towards – and past – damaging tipping points. And I think our best – and possibly last – hope of avoiding those bad tipping points is through finding and triggering some positive tipping points in human systems that transform our society’s technology, and our relationship with the rest of the Earth system.”

Carbon Brief was at the conference and in this article draws together some of the key talking points, ideas and proposals that emerged.

- Tipping points

- Biggest concerns and early warnings

- Interacting tipping points

- Positive tipping points

- Putting positive tipping points into operation

- Climate justice

- Research initiative

- IPCC special report and MIP

Tipping points

In the opening plenary, Prof Lenton set out the concept of a tipping point in the Earth system.

Using an animation of a ball rolling around in a basin (see below), Lenton explained that, as with “many complex systems”, this illustration “has two alternative stable states to start with”. The ball starts off in one basin – the depth of which represents how stable that state is.

Pressure on the system causes the left-hand basin to become unstable. The ball is pushed around in the basin by short term variability – akin to weather events in a climate system.

Eventually, the ball is pushed past the tipping point of the increasingly unstable left-hand basin and it falls abruptly into the other basin. Here, it is in a new stable state from which it cannot easily return. (The right-hand chart shows a timeseries tracking the movement of the ball between states.)

Animation showing an illustration of a tipping point. The left-hand box shows a system with two states, where the ball indicates which state it is in and the depth of each basin shows how stable that state is. The right-hand box shows a timeseries tracking the movement of the ball between states. Credit: Chris Boulton.The crux of this kind of behaviour is a “reinforcing feedback” within a system that “gets so strong it [becomes] self-propelling”. Lenton used a further example of a fire alarm going off in the building:

“If one person hearing the fire alarm and running for the exits causes two more people to run, that causes four to run, that causes eight to run, then we have a self-propelling runaway feedback situation and a tipping point.”

There is “ample scientific evidence” to show that the world is at risk of “tipping point shifts that can have major, long-term, irreversible impacts”, added Prof Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and joint convenor.

Biggest concerns and early warnings

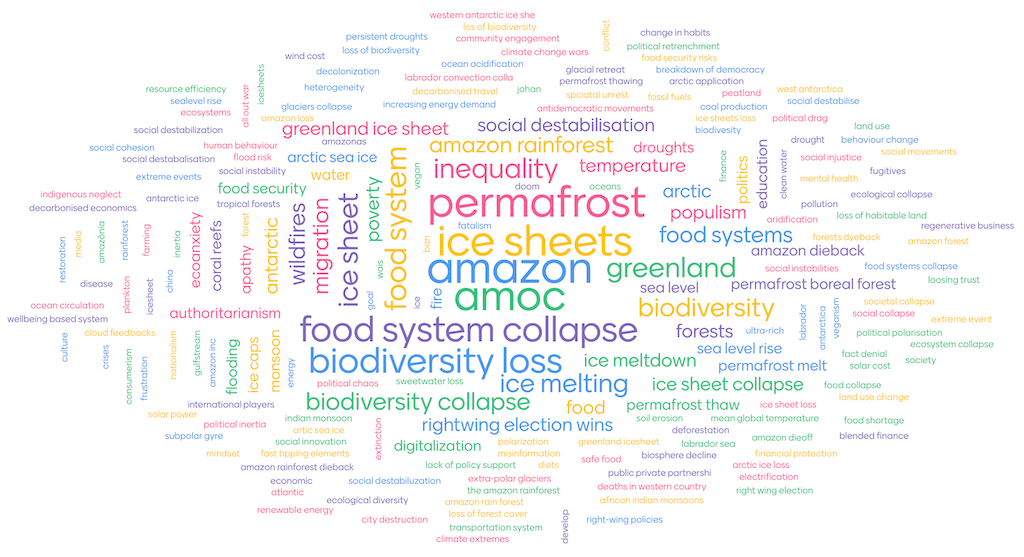

Lenton and Rockström ran a quick poll to ask conference participants which tipping “element” in the Earth system they were most concerned about. The resulting word cloud – shown below – highlights those that participants picked out.

Several of the tipping elements that feature most prominently in the poll results were covered in talks and discussions on the opening day.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Sir David King, UK special representative for climate change during 2013-17 and founder of the Centre for Climate Repair at the University of Cambridge, agreed that tipping points for melting ice sheets represented a great cause for concern. He said:

“I think what we’re learning is the amount of really high level work that’s been done on tipping points…the Arctic Circle is a region where the tipping point has already begun. It’s end-game if we let this continue.”

In her talk, Prof Ricarda Winkelmann, professor of climate system analysis at PIK, explained how the Earth’s ice sheets are “not only some of our most amazing climate archives through which we learn about the climate history of Earth, they’re also some of our most effective early warning systems”.

Winkelmann unpacked her 2020 study that identified a “sequence of tipping points for Antarctica”. This includes a “major threshold at somewhere between 1.5C and 3C of warming”, which would cause “the collapse of west Antarctica”. There are further thresholds for East Antarctica at between 3C and 6C of warming and above 6C, she added.

For Greenland, research shows that a critical threshold lies “between 0.8C and 3.2C”, above which “it could be a near-complete loss of the Greenland ice sheet”.

This research shows that Antarctica and Greenland are among the Earth’s “most vulnerable” tipping elements, said Winkelmann, adding that “once some of that ice volume is lost, we cannot get it back easily”.

“We really are a geological force”, says @Ricarda_Climate, who adds that human emissions in the coming few years will “lead to changes in the Earth’s system for hundreds or even thousands of years”.#tippingpoints

— Robert McSweeney (@rtmcswee) September 12, 2022

Prof Stefan Rahmstorf, co-head of research department on Earth system analysis at PIK and professor of physics of the oceans at the University of Potsdam, presented on the question of whether the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is “approaching a tipping point”.

The AMOC is a major system of currents in the Atlantic Ocean that brings warm water up to Europe from the tropics and beyond.

Rahmstorf referenced research from 2021 that found the AMOC is “in its weakest state in over a millennium”. But, he added, “a couple of weeks ago, I was at the International Conference on Palaeooceanography, where I saw some as-yet unpublished proxy data saying this is going back even much further in time – it’s probably at its weakest [for] the entire Holocene by now”. (Approximately the last 11,700 thousand years.)

A tipping point in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is “very well established physics”, says @rahmstorf

— Robert McSweeney (@rtmcswee) September 12, 2022

There’s still a “big uncertainty” around how far away it is, but recent studies show it is “maybe too close for comfort”#tippingpoints2022

Prof Niklas Boers, professor of Earth system modelling at the Technical University of Munich, presented on the concept of “critical slowing down” – the idea that as a system becomes less stable, it responds more slowly to the pressures placed on it.

For example, in a study from earlier this year, Boers and his co-authors found that three-quarters of the Amazon rainforest has lost “resilience” since 2003 through deforestation and climate change. This “may already have pushed the Amazon close to a critical threshold of rainforest dieback”, the study says.

In his talk, Boers explained that this could have a knock-on impact for the South American monsoon:

“The South American monsoon is strongly coupled with the Amazon rainforest because of the moisture recycling – and the degradation of the Amazon and the deforestation can lead to an abrupt transition in that monsoon system as well, which would then put also the southern parts of South America at risk because it would reduce precipitation by 30 to 40%.”

Observed rainfall data for the South American monsoon also show “indications of critical slowing down, implying that also that system is moving towards a critical threshold”, noted Boers. He concluded:

“There is observation-based evidence that some major Earth system tipping elements are losing stability. Indeed, real-time monitoring of those systems is possible and should really be done. Data-based analysis really only allows us to say what happened up to now and we need to improve our models to be in a better position to say what happens next.”

For the Amazon, the influence of both warming and deforestation means that there are two ways to influence where a tipping point lies, noted Dr Chris Boulton, the lead author on the Amazon resilience paper and co-lead for a breakout session on early warning indicators. He explained to Carbon Brief:

“Not only do you have the climate-change uncertainty, you also have the social uncertainty. So I can imagine a scenario where if you can stop that deforestation from happening then that can change where that threshold is…You can bring tipping points closer, but with positive action you can push them further away as well.”

Knowing exactly where that threshold lies is still very tricky, Boulton added. Just looking at the average state of a system might not reveal it is changing over time, he said. Instead, it is necessary to “really delve into” higher-order statistics in order to “see that these changes are happening”.

Interacting tipping points

Day two began with a plenary on “interacting tipping points”. Dr Juan Rocha, a research scientist at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, was the first speaker of the session.

Rocha opened by introducing the concept of a “regime shift” – a “large, abrupt and persistent change[] in the functional structure of ecosystems”. He explained that these systems generally have “nonlinear dynamics” which makes them “very difficult to predict” and “hard or impossible to reverse”. An example of this is the dieback of a forest, he said.

Regime shifts can interact, Rocha explained. For example, he said a regime shift in coral reefs can lead to coastal erosion, which in turn can lead to nearby mangrove ecosystems “tipping over”.

In a recent study, Rocha and his team used the Regime Shift Database to develop “network models” linking together multiple different ecosystem regime shifts in the climate system. His work showed that in some instances, interactions between different ecosystems can lead to tipping cascades, in which one tipping point can trigger another, he explained.

Rocha noted that climate change is “a central mechanism” to trigger a tipping cascade, but that other mechanisms – such as urbanisation or deforestation – can trigger tipping cascades even earlier.

This might make you “sad”, Rocha said, but he added:

“I would like to flip the coin and highlight that multiple mechanisms also means multiple points for action. And that means empowering actors at the local to regional scale to make a difference…If you remove a domino here or there, you will stop the cascade.”

Can the occurrence of one #TippingPoint lead to another tipping point being triggered?

— Daisy Dunne (@daisydunnesci) September 13, 2022

A slightly terrifying question from @juanrocha to start off day two of #tippingpoints2022

Evidence that many tipping points could overlap, particularly on land, he says pic.twitter.com/cEpynhIeiP

In his talk, Dr Steve Lade, an ARC future fellow at the Australian National University, explained the relevance of “planetary boundaries”, describing “a way to group tipping points within these nine biophysical systems such as biosphere integrity, climate, water, nutrient cycles etc”.

There is a “dense network of connections between the planetary boundaries”, Lade said. He went on to share the results of a study he published recently, which found evidence for interactions between more than half of the different pairs of planetary boundaries.

He continued:

“The net effect of these interactions is to amplify human pressures on the Earth system…Another way of looking at that same thing is the fact that the safe operating space for human activity in the Earth’s system shrinks as a result of these interactions.”

Lade concluded:

“Even before we reach tipping cascades, planetary boundaries and social ecological interactions can also accelerate us towards those tipping points. It can shift tipping points close to us, and it could even create entirely novel tipping points.”

Eco and social interactions could “accelerate us towards #TippingPoints” and “even create novel tipping points”, says @StevenLade

— Daisy Dunne (@daisydunnesci) September 13, 2022

Two examples include how warming leads to more air con use (and so more warming!) and how forest loss leads to timber scarcity#tippingpoints2022 pic.twitter.com/RE0c77PzHs

In her talk, Dr Patricia Pinho, a researcher at Stockholm Resilience Centre, explained that framing changes in the Amazon through the lens of social tipping points is a “novel” but important concept, which she worked to implement in the latest report on climate impacts by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Pinho shared her work on the impacts of climate change on communities in the Amazon, and concluded that “from the point of view of people, the tipping point is already happening”, because the exposure, frequency and intensity of extreme events is already rising.

Laura Wellsley, a senior research fellow at Chatham House, took to the floor next, to discuss the idea of food system tipping points stemming from the war in Ukraine.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we have seen “a collision of many of the worst systemic weaknesses of our global food system that together create conditions for rapid risk cascades around the world”, Wellsley said.

For example, she pointed to the small number of major breadbaskets that the world relies on for food, and the limited number of routes through which it can be distributed. She concluded:

“The war in Ukraine, the pandemic before it, and worsening climate impacts on the food system should be enough to push us into a different system – to push us to the point where there’s recognition that this system is not fit for the future. But the status quo in the food system has shown remarkable resilience to repeated and coincided supply shocks.”

Climate change is creating a “base level of risk” on top of which shock events such as the invasion of Ukraine “really can escalate” food system #TippingPoints, says @LauraWellesley

— Robert McSweeney (@rtmcswee) September 13, 2022

“Our adaptive capacity is really weakening,” she adds.#tippingpoints2022

The final speaker of the session was Prof Oonsie Biggs, co-director of the Centre for Sustainability Transitions (CST) at Stellenbosch University in South Africa. She shifted the framing of the session to discuss social, ecological and socio-ecological tipping points. For example, Biggs explained how the domestication of plants and animals “spurred a whole lot of other developments”, setting up the conditions that led to the industrial revolution.

Positive tipping points

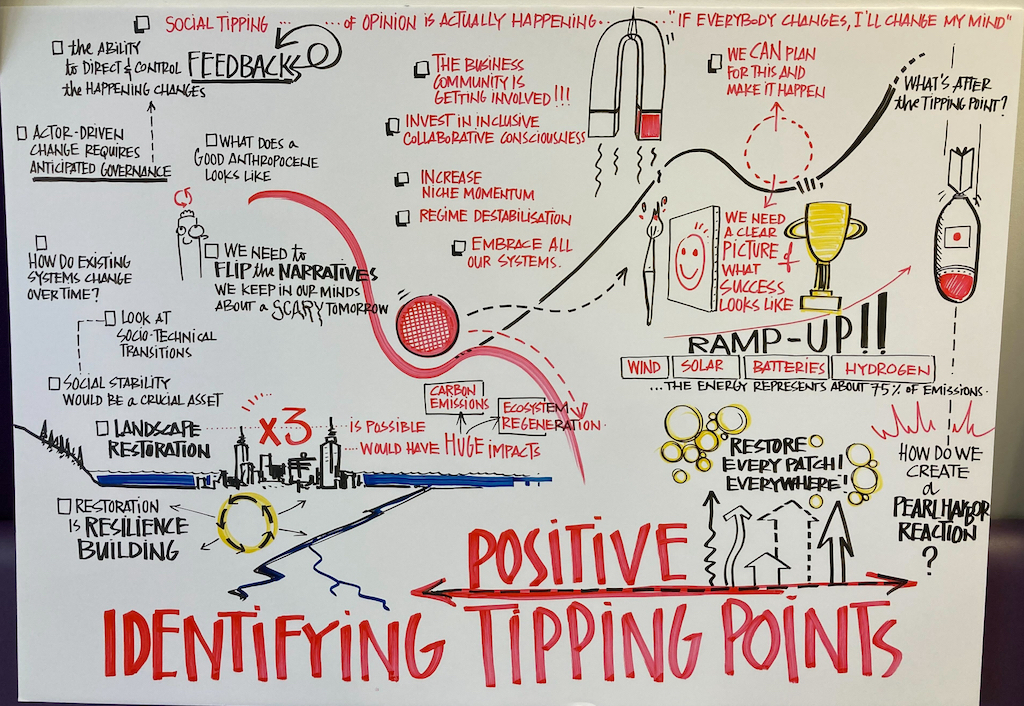

The conference’s third plenary session was dedicated to identifying “positive tipping points” in social systems – the idea that small nudges can lead to rapid social change, potentially accelerating action on climate change.

The idea of positive social tipping points uses the same line of thinking as tipping points in the climate system, but it would be wrong to assume that they work in the same way, argued Prof Frank Geels, a professor of system innovation at the University of Manchester. He told the conference:

“Tipping points in the natural sciences are pretty well defined. There are certain thresholds, often defined by a single control variable, where small additions or actions can suddenly and rapidly tip a system in a different state due to deterministic self-reinforcing feedbacks.

“In the social sciences, I don’t think it works exactly the same way…The thing that is really appealing to policymakers is the idea that we only have to do something really small and then we see these huge effects, which is pretty misleading because it’s primarily the efforts leading up to the tipping point where a lot of effort will actually be needed.”

We’ve moved on to “positive #TippingPoints” – the idea that small nudges can lead to rapid social change

— Daisy Dunne (@daisydunnesci) September 13, 2022

But @FrankGeels explains it’s often not as simple as that: “The idea of small actions having a bit effect is appealing but it ignores the long lead up.”#tippingpoints2022

He offered two examples of where multiple factors have worked in tandem to trigger a positive “tipping point” towards accelerated climate action.

One was the rollout of electric vehicles in the UK. Globally, EV uptake has been driven by cheaper electric batteries – which have dropped in cost by 90% since 2010 – as well as improved driving range and other technological advancements.

These factors have led to more uptake in the UK, which has, in turn, driven more car companies to invest in product development and politicians to implement policies to phase out petrol vehicles, Geels argued. He added that EVs have been propelled further still by outrage over dieselgate and concerns about air pollution from petrol cars.

“It’s both the increasing momentum of the new innovation as well as the destabilisation of the old which has really led to a tipping point around 2015-17,” he told the conference.

Geels offers a couple of examples:

— Robert McSweeney (@rtmcswee) September 13, 2022

1. Shift towards EVs and away from diesel cars 2015-17 (cheaper batteries, longer range, dieselgate, etc)

2. Shift to offshore wind and away from coal 2009-17 (cheaper/more efficient turbines, negative view of coal, etc)#tippingpoints2022

Several other speakers in the session questioned the analogy between climate tipping points and positive social tipping points.

In her talk, Dr Manjana Milkoreit, a researcher of sociology and human geography at the University of Oslo, raised concerns about the “assumptions” climate scientists had made about the potentials of positive social tipping points.

She pointed out that there is no guarantee that positive tipping points exist in all social systems and, if they do exist, they may be difficult to control with policy interventions.

She added that, as well as holding the potential for positive tipping, many social systems also contain self-regulating negative feedback mechanisms to prevent rapid change to a new state. She told the conference:

“We have a whole bunch of social mechanisms and institutions and processes that guard against nonlinear change, and rein in feedback processes. So maybe we’re different in important ways in social systems.”

And in another talk, Dr Laura Pereira, Exxaro research chair at the Global Change Institute at University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, urged delegates to “reimagine” what global social change could look like – pointing out that a positive social tipping point might look different from an African perspective.

Social #TippingPoints are something that might “get us on a better track”, says @laurap18

— Robert McSweeney (@rtmcswee) September 13, 2022

But are they:

Restorative: to get back to something we’re yearning for; or

Transformative: something fundamentally different – what a good Anthropocene might look like#tippingpoints2022

The other two speakers in the session put forward examples of where they see positive social tipping points leading to transformative change.

Dr Dennis Garrity, chair of the board of the Global EverGreening Alliance – a group of 71 conservation and development organisations – said that he believed a number of burgeoning land-based initiatives, including regenerative agriculture, rewilding and holistic rangeland management, could lead to a positive tipping point for land restoration.

(In March, Carbon Brief covered a key UN report finding humans have altered 70% of Earth’s land surface, degrading 40% of it.)

Garrity told the conference:

“These are the early days, but the signs are beginning to point humanity toward a new land ethic, a new focus on land care. If we can tip into this and create a national restoration movement in countries around the world, then there is a serious prospect that land restoration will play a huge role in turning emissions into removals – producing livelihoods, biodiversity, water and other co-benefits as well.”

Rewilding, regenerative agriculture and managed rangelands

— Daisy Dunne (@daisydunnesci) September 13, 2022

These are “tipping elements” that may eventually lead to a positive #TippingPoint for land restoration, says Dennis Garrity @EvergreeningA

#tippingpoints2022 pic.twitter.com/3WWRXr3XFV

Prof Doyne Farmer, director of the complexity economics programme at the Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford, told the conference about the results of his recent study finding that switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy could save the world as much as $12tn (£10.2tn) by 2050. Farmer explained:

“We can make the green energy transition quickly and in a purely economic profit. That is, even if you’re a climate denier, you should be behind making green energy transition quickly – and when I say quickly, I mean, in 10 to 20 years. To do this, we need to continue to ramp up wind, solar, batteries and hydrogen fuels at existing rates for another decade or two.”

You should want a green energy transition “even if you are a climate denier” – purely for economic reasons.

— Ayesha Tandon (@AyeshaTandon) September 13, 2022

Doyne Farmer discusses how the economics of green is likely to accelerate the green energy transition.#tippingpoints2022 pic.twitter.com/WlkBtlHEjz

Ramping up renewable energy would require policymakers to address some “roadblocks”, he added:

“This is a classic example of what we call a ‘sensitive intervention point’ – I think it’s the same as a social tipping point – except that we like the word sensitive intervention because this is a place where if we can just remove a few roadblocks, we can eliminate 75% of emissions in 20 years or less.”

Putting positive tipping points into operation

The session’s final plenary session was dedicated to “operationalising” positive tipping points (see above) – drawing on the perspectives of a diverse group of economists, activists and policymakers.

The session’s first speaker was Kate Raworth, an ecological economist at the University of Oxford and creator of the “doughnut theory” of economics, a visual framework consisting of two concentric circles symbolising Earth’s planetary boundaries and social boundaries. The theory suggests living within these two circles to meet both the planet’s and people’s needs.

Enjoying @thefabians‘ recent report on environmental policy. Great for understanding UK context on this as well as new ways of thinking about sustainable development. Here’s a diagram illustrating @KateRaworth‘s ‘doughnut economics’ idea. Light green area’s the promised land. pic.twitter.com/RfLWZoXj1g

— Rich Collett-White (@RichardCollettW) April 8, 2018

Raworth explained how the theory’s popularity exploded after the city of Amsterdam adopted it as a basis for public policymaking in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. Since then, cities across Europe, North and South America and Australia have shown an interest in adopting the theory, she said.

She described the doughnut economics project as one tool in a wider movement towards “transformative” social change:

“We’re part of a movement for transforming economic thinking, moving from endless growth to thriving in balance.”

Last morning of #tippingpoints2022 and we’re hearing about how to turn positive #TippingPoints into action@KateRaworth explains how her “doughnut economics” theory has spread across cities globally

— Daisy Dunne (@daisydunnesci) September 14, 2022

She says it all kicked off after this Guardian article: https://t.co/uPS0kNRxIQ

The next speaker was Simon Sharpe, director of economics for the UNFCCC Climate Champions, a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute and former deputy director of the UK government’s COP26 unit.

He told the conference about his recent research examining how to harness potential social tipping points to meet climate goals.

The research offers two examples of what it describes as small policy changes that have already led to positive social tipping points being triggered at a national level.

One example is the rapid adoption of electric cars in Norway. Globally, EVs account for 9% of new car sales. However, in Norway, they accounted for 54% of all new vehicle sales in 2020, according to the research. (The figure is now even higher.)

Referring to Geels’ earlier explanation of why EVs have spread rapidly (see section above), he told the conference:

“Norway added to that a lot of their own policies and – one that they themselves said made a critical difference – the combination of tax and subsidy that made electric vehicles cheaper to buy than petrol cars. The result: an electric vehicle share of car sales 10 times higher than the European average and about 20 times higher than the global average.”

He added that he believed more social tipping points could be “unlocked” if the government changed the way it viewed the economy:

“To activate tipping points more often and to make faster progress, we actually need a transition in ideas. At its fundamental level, it’s a shift in how we understand the economy, from it being an equilibrium system to being a dynamic system that is always evolving.”

The third speaker, Femke Sleegers, a cultural psychologist and climate activist behind the Social Tipping Point Coalition in the Netherlands, explained how, in her view, the work of small activism groups could build together to reach a new social tipping point. She told the conference:

“History has proven small groups can change the world.”

Giving a civil society perspective on social #TippingPoints, @Fem015 says:

— Robert McSweeney (@rtmcswee) September 14, 2022

“History has proven that small groups can change the world”#tippingpoints2022

The session also heard from Daniel Godfrey, an independent non-executive director at Moneybox, an investment app, about how investment can be “fixed” to help meet the world’s climate goals.

The final speaker was Scarlett Benson, co-director of knowledge generation at the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU), who told the conference about potential positive tipping points in the food system.

Her talk explained that triggering positive tipping points in the food system relied upon “enabling conditions for positive tipping”, such as the right price, performance – “Does the alternative burger taste as good?”, accessibility – “Do I need to go to Whole Foods to buy that or can I go to Sainsbury’s?”, acceptability within cultural norms and capability.

.@scarlett_bens of @SYSTEMIQ_Ltd & @FOLUCoalition outlines the enabling conditions for social #TippingPoints:

— Robert McSweeney (@rtmcswee) September 14, 2022

– Cost competitiveness

– Performance

– Accessibility

– Cultural norms

– Capability#tippingpoints2022

Climate justice

The importance of climate justice was stressed repeatedly throughout the conference.

In a day one plenary session, climate activist and filmmaker Ashish Ghadiali argued that climate justice is central to the tipping points “agenda”, and invited attendees to “consider over the course of the next few days how far the work that you do is actually climate justice”.

For example, he explained that the 1.5C warming threshold is “a question of existential threat” for the most vulnerable countries. He said that this threshold had been formally adopted in 2015 in part due to pressure from climate justice groups.

The decision to commission an IPCC report on 1.5C shows that “the scientific endeavour – whether it was conscious of it or not – was an incredibly important factor in this movement towards climate justice”, he added.

It’s important to remember the “human face” of climate tipping points and the link to #ClimateJustice, says @ashghadiali

— Daisy Dunne (@daisydunnesci) September 12, 2022

“We’ve all been shocked by the images from Pakistan, where melting glaciers combined with a vulnerability related to lack of resources.”#tippingpoints2022 pic.twitter.com/Y1bt3edxvM

In the panel session that followed, Prof Winkelmann explained that “thinking about tipping points in the climate system also means thinking about intergenerational justice”.

In another plenary, Dr Pinho explained that the Amazonian areas most severely affected by climate extremes, such as flooding and droughts, are typically inhabited by indigenous people and local communities.

Pinho added that these groups typically “have a colonial legacy of exploitation”. She also noted that these groups typically benefit the least from land-use change, concluding that a climate justice framework is needed to reduce vulnerability.

@patipinho10 says a climate justice framework is needed to address impacts in rural Amazonian communities

— Ayesha Tandon (@AyeshaTandon) September 13, 2022

“The inclusion of local communities and indigenous people in decision making will really help to reduce their vulnerability to this compounding hazards”#tippingpoints2022 pic.twitter.com/pWhQVWj7U8

Meanwhile, Prof Geels highlighted the “tension” between achieving a “rapid” and a “just” transition. He said “there will be a lot of losers along the way” and suggested that one way of ensuring a just transition is to compensate them.

Geels added:

“Politicians are increasingly working with big finance with big companies who are not so interested in ethical and justice questions…I think politicians increasingly are [prioritising] speed over justice.”

In a separate session, Dr Pereira discussed the importance of including diverse voices in discussions around what a future society might look like.

Learning about social tipping points at #tippingpoints22

— Ayesha Tandon (@AyeshaTandon) September 13, 2022

Do we want to return our society back to what we are used to? Or move forwards to something new?

Laura Periera discusses the importance of including diverse voices in these discussions pic.twitter.com/aoj0wIxbZw

Throughout the conference, more informal breakout sessions saw attendees splitting off into different rooms to discuss topics ranging from modelling tipping points to identifying positive tipping points around coal use.

In a two-part breakout session dedicated to climate justice, members discussed how to progress the climate-change agendas in their own work. The sessions culminated in the proposal of a climate justice “hub”. Ghadiali – a co-lead of the session – told Carbon Brief what the hub hopes to achieve:

“The proposed hub was identified as being a space for learning where researchers, communicators, activists and funders can learn more about climate justice in the context of unfolding geopolitical and biopolitical events, explore approaches to develop the justice-based application of current projects, participate in collaborative and interdisciplinary networks, and identify new opportunities for research and engagement.”

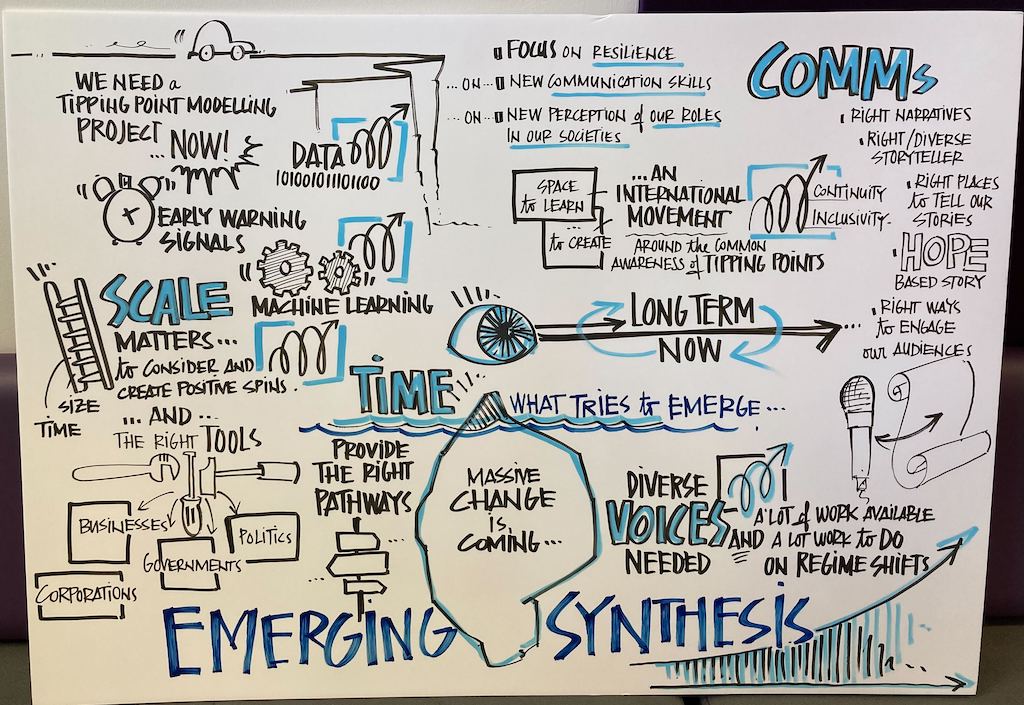

Research initiative

The conference saw the launch of a new initiative, funded by a £1m grant from the Bezos Earth Fund, to “improve the assessment, forecasting and activation of positive tipping points”.

There are three elements to the project, Lenton explained to Carbon Brief at the conference, in much the same way that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has three working groups.

The first aim is to “give the world an authoritative update on the state of different economic sectors and countries towards positive tipping points”, said Lenton. This will be ready in time for the COP27 climate talks in Egypt this November.

The second aim is to “do some substantive research to see if there are early indicators that a sector is heading towards a positive tipping point”, continued Lenton.

If there are, then “it gives policymakers, investors and whoever else a very clear indication of where they’re going to get the biggest return on their investment in terms of creating positive, transformative change”, Lenton said.

Finally, the third aim is to “try to produce a first-ever state of [positive] tipping points report ready for COP28 [in the United Arab Emirates] in November 2023”.

Part of the purpose of the conference, set out on its website, was also as a “call to action” to form a “research alliance” that will “improve warnings of the proximity of catastrophic climate tipping points and to accelerate positive tipping points to avert the climate crisis”.

This alliance started out as a collaboration between the University of Exeter and PIK, but Lenton said that “we didn’t just want it to be the two of us”, adding:

“We wanted to put a marker down, but we wanted to grow and to invite other leading key institutions and the people in them to be part of it.”

This alliance will “hopefully help write the state of tipping points report”, Lenton explained, while also making sure the report ahead of COP27 is “as up-to-date and well informed as it can be”.

Lenton also hopes that this alliance – which had a dedicated session at the end of the conference – will help inform an “agenda-setting” scientific paper on tipping points research “across the board”. This may involve working towards publishing one or more special issues on tipping points in academic journals, he added.

IPCC special report and MIP

Another idea discussed at the conference was for an IPCC special report on tipping points in the climate system. In a public “great tipping points debate” session, Prof Thomas Stocker – professor of climate and environmental physics at the University of Bern and former IPCC co-chair – explained why Switzerland has proposed such a report on tipping points “and their implications for habitability and resource”. He said:

“We need to open up the channel to policymakers and one of the best experiences we have for the channel from science to policymakers is the IPCC assessment.”

Stocker added that such a special report “should be commissioned” in the seventh assessment cycle of the IPCC, adding:

“I’m sure that just as the special report on extreme events [in 2012], this report will accelerate all of our understanding, modelling capability [and] observations. So please join Switzerland’s effort in proposing a special report [to the] IPCC.”

Lenton noted that, “as I understand it, there needs to be another major nation” under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to “back that call”. But, he added, “many of us in the science community feel that it’s a vital, timely initiative…it would really bring this crucial element of assessing the risks we’re facing into full view”.

Another proposal discussed at the conference was for a Tipping Point Model Intercomparison Project (TIPMIP). Model Intercomparison Projects – or “MIPs” – are collective specialised experiments in which climate modelling groups around the world can choose to participate. Formal MIPs are overseen by the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP).

The TIPMIP is needed because “we are still lacking a systematic, multi-model approach to understanding and estimating tipping points for different subsystems of the Earth system”, Prof Winkelmann told Carbon Brief at the conference.

The aim would be to learn about “some of the key feedbacks and interactions between tipping elements”, explained Winkelmann – “particularly the core tipping elements that have an influence on the entire Earth system”. In addition, the MIP would help “get a better and systematic understanding of the critical thresholds” within these tipping elements.

Winkelmann is also keen to look at the potential impacts of tipping points “beyond what we typically look at for climate projections”, which is usually up to 2100. This is because the impacts of crossing tipping points may well “unfold on much longer timescales”.

Working within a MIP would mean that different research groups could all “use the same experimental protocols for each of the tipping elements”, Winklemann said, adding that “the invitation is open to every modelling group”.

-

Tipping points: How could they shape the world’s response to climate change?

-

Highlights: Major conference issues ‘call to action’ on tipping-points research