In-depth Q&A: How the EU plans to end its reliance on Russian fossil fuels

Josh Gabbatiss

05.20.22Josh Gabbatiss

20.05.2022 | 1:55pmSolar panels on every new home and a ban on fossil-fuel boilers by the end of the decade are among the proposals in a new EU plan to completely end the bloc’s reliance on Russian fossil fuels.

The European Commission has released its REPowerEU strategy, responding to the “double urgency” of dependence on Russia and climate change.

In cutting ties with Moscow “well before 2030”, the strategy sees gas consumption in the EU falling by two-thirds – much faster than previously anticipated – and renewable power capacity doubling over the next eight years.

To help cut gas use more quickly, the commission proposes a higher 45% target for renewables’ share of the EU energy mix in 2030, up from the 40% goal proposed only last July. It also suggests a more ambitious target for energy savings, cutting demand 13% by 2030, from a 2020 reference point, instead of the current 9%.

While framing the plan as an acceleration of the EU’s climate strategy, the headline goal of cutting emissions to 55% below 1990 levels by 2030 remains unchanged.

Moreover, the detailed figures behind the commission’s proposals show that it expects coal use to fall more slowly under the new strategy, ending the decade 41% higher than previously planned to plug some of the gap left by gas.

The EU’s simultaneous scramble to expand fossil-fuel infrastructure both domestically and abroad has also come under fire. Of the €300bn the commission says will be needed for REPowerEU by 2030, 4% is pegged for new oil and gas pipelines and terminals.

The bundle of proposed legislation and more informal guidance that forms REPowerEU will now feed into on-going negotiations around the bloc’s climate policies.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief explains the significance of these new plans, how they fit into existing EU climate targets, and the bloc’s broader international energy policies.

- Why is REPowerEU being launched?

- What are the plans for expanding renewables?

- What is the role of energy efficiency and savings?

- What will the new proposals mean for EU fossil fuel use?

- How much will the plan cost?

- How will the EU work with other countries?

- How does this link to the EU’s wider climate strategy?

Why is REPowerEU being launched?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sparked significant societal pressure for the EU to stop helping to finance the war through its imports of fossil fuels.

As by far the largest supplier of oil, gas and coal to the EU, Russia has received more than €50bn in fossil-fuel payments from its European neighbours since the war began.

Speaking to Carbon Brief at an event in Berlin, Anna Ackermann a founding member of the Ukrainian NGO EcoAction, questioned why Europe continued to pour funding into Russia while in Ukraine they were “counting deaths…every single day”:

“This is the moment in history where we should finally realise how many problems fossil fuels bring, not only on climate…but also for energy security.”

The EU acted relatively quickly on sanctioning Russian coal and, as it stands, imports will end by mid-August. While the bloc has been importing around 70% of its thermal coal from Russia, this is a large share of a relatively small volume and has proved easier to phase out.

The real challenge for the EU has been Russian oil and gas, which account for the bulk of its fossil-fuel export revenues.

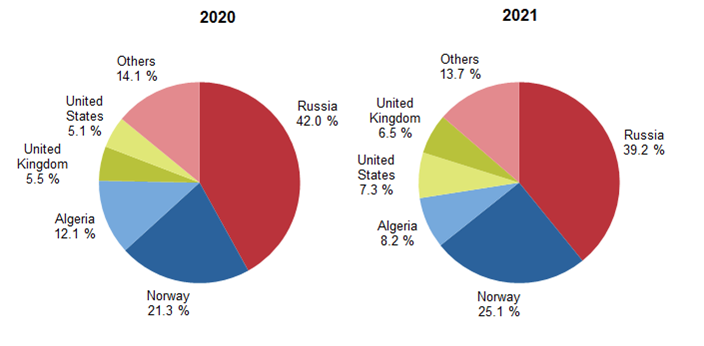

Russia provided the EU with 39% of its natural gas and 25% of its oil in 2021. As the charts for gas imports below show, this far exceeds the EU’s other major trading partners for fossil fuels, such as the US, Norway and Algeria.

Some EU member states, particularly northern and eastern nations, are particularly vulnerable given their reliance on Russia for more than half of their fossil fuel imports.

With all of this in mind, the European Commission first outlined its idea for REPowerEU in early March, describing it as a “plan to make Europe independent from Russian fossil fuels well before 2030, starting with gas, in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”. This included a short-term goal of cutting demand for Russian gas by two-thirds before the end of 2022.

The commission has also put forward proposals to phase out Russian oil by the end of the year, which are now being discussed by member states.

The initial REPowerEU communication was followed by an informal meeting of EU heads of state that resulted in the Versailles declaration and then EU Council conclusions that gave formal support for a plan to eliminate Russian gas, oil and coal imports “as soon as possible”.

Various businesses and civil society groups argued that REPowerEU should be an opportunity to reframe renewable power and energy efficiency as measures to secure the EU’s energy supply, rather than turning to other sources of fossil fuels.

The full REPowerEU package, which is made up of strategies, legal documents and guidelines, focuses on saving energy and replacing fossil fuels with clean energy on the one hand, while, on the other hand, finding replacement sources of fossil fuels and building new fossil-fuel infrastructure.

Ahead of the launch of the plan to get off Russian fossil fuels, there was debate over the extent to which it would – or should – lean towards using renewables and energy saving, versus finding alternative sources of coal, oil and gas.

In the event, some 80% of the expected reductions in gas use by 2030 are due to come from non-fossil sources, primarily renewables and energy saving. And 96% of the additional investment proposed by the commission would similarly be targeted towards non-fossil energy.

Notably, the commission explicitly frames its proposals as an “additional investment” that will quickly pay off by cutting the EU’s bill for fossil-fuel imports. This is in marked contrast to earlier debates over whether the EU’s climate goals were a cost to be managed or an investment in reducing the bill for fossil fuels. A factsheet on financing the new plans says:

“Additional investments of €210bn are needed between now and 2027 to phase out Russian fossil-fuel imports, which are currently costing European taxpayers nearly €100bn per year.”

On the launch of the plan, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen told a press conference that the new strategy builds on the EU’s existing climate goals:

“Today, we are taking our ambition to yet another level…I would say that this will be the speed charging of the European green deal.”

However, whether or not the proposals are integrated into law and followed by EU nations now rests with member states and the European Parliament, and decisions will emerge in the coming months.

What are the plans for expanding renewables?

The main REPowerEU strategy includes a number of significant new targets for renewable energy.

Indeed, the vast majority of new investment the commission says will be required to support its plan are for solar, wind and other low-carbon technologies.

The commission recommends raising the ambition of the Renewable Energy Directive, increasing its target to 45% of the EU energy mix being renewable by 2030, which it says would require 1,236 gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar capacity. This is up from the 40% target – and 1,067GW – in the Fit for 55 proposals last year.

This would mean roughly doubling the renewable share of EU energy supplies over the next eight years, from 22% in 2020.

Within this, the strategy specifically identifies solar power as “one of the fastest technologies to roll out”. It proposes doubling current solar installations to 320GW by 2025 and then again to 600GW by 2030.

The package also includes a new EU solar strategy, which contains details of how the commission would like to achieve these targets.

This includes a proposal that received a lot of coverage in the lead-up to the strategy’s launch – the EU solar rooftops initiative. The strategy states that by some estimates, rooftop solar could provide one-quarter of EU electricity. The initiative suggests that the installation of rooftop solar panels should be compulsory for:

- New public and commercial buildings by 2026

- Existing public and commercial buildings by 2027

- New residential buildings by 2029

Wary of increasing imports from Asian countries, the commission also proposes an EU Solar Industry Alliance and a “large-scale skills partnership” as measures to scale up the region’s solar workforce and industrial capacity.

Another potentially significant proposal involves loosening planning restrictions for new wind and solar projects by requiring member states to set aside “go-to” zones within their borders where approvals can be fast tracked due to lower environmental standards.

While these proposals are ambitious, NGOs had been calling for the EU to go further, proposing a 50% target for renewable energy by 2030 so as to further reduce its reliance on imported gas.

(Separately from the commission proposals, four EU member states this week said they would aim for a tenfold increase in offshore wind capacity from 15GW to 150GW in 2050.)

The commission frames low-carbon hydrogen and biomethane as key components in its strategy to reduce reliance on Russian gas – replacing 44bn cubic metres (bcm) of gas imports in total by 2030 – and to decarbonise sectors such as heavy industry.

REPowerEU sets a target of 10m tonnes of domestic renewable – or “green” – hydrogen production and 10m tonnes of renewable hydrogen imports by 2030. (Notably, unlike the UK, the EU is not planning to develop “blue” hydrogen made from gas.)

This hydrogen target is an increase from around 6.6m tonnes the commission said would be produced domestically in the Fit for 55 scenario – although the EU Hydrogen Strategy mentions “up to” 10m tonnes by 2030. The commission’s “staff working document” says of the imports that 6m tonnes would be renewable hydrogen and 4m tonnes would be in the form of ammonia, which is easier to transport and can be converted back into hydrogen.

Some civil society groups are sceptical about these goals, with Raphael Hanoteaux, a senior policy advisor on gas politics at E3G, telling Carbon Brief that both this and the biomethane target are “unrealistic”.

Specifically, he points to a mismatch between the renewable power capacity available and the volumes of green hydrogen that would need to be produced under the commission’s proposals.

The commission itself acknowledges some uncertainty around hydrogen, stating that:

“In particular, renewable hydrogen needs new production capacity and dedicated transport infrastructure; and may only start to contribute significantly after 2027.”

A biomethane action plan also accompanied the strategy, including a new Biomethane Industrial Alliance and financial incentives to increase production in the EU to 35bcm by 2030.

A recent report by the German Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IFEU) concluded that a realistic biomethane target for the EU would only be 17bcm by 2030, around half the commission’s target.

What is the role of energy efficiency and savings?

Energy savings are identified as a key part of REPowerEU’s approach, as the document states:

“Savings are the quickest and cheapest way to address the current energy crisis. Reducing energy consumption cuts households’ and companies’ high energy bills in the short and long term, and decreases imports of Russian fossil fuels.”

Perhaps the most notable proposal is an amendment to the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED), which would increase its binding target from the Fit for 55 level of 9% to 13%.

This means that EU countries would have to ensure an additional reduction of energy consumption of 13% by 2030, compared to 2020 reference scenario projections.

In practice, this could involve improving the performance of industrial processes and transport, but one aspect that is often highlighted is the need for mass building renovations to improve energy efficiency.

Analysis by the Buildings Performance Institute Europe has demonstrated that improved insulation in a selection of member states could result in up to 44% gas savings and cut final energy demand by 45%.

With this in mind, the commission calls on the European Parliament and member states to “enable additional savings and energy efficiency gains in buildings through the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive [EPBD], and to uphold the ambition of the commission proposal for a Regulation on Ecodesign for Sustainable Products”.

An updated version of the EPBD, which contains stronger “minimum energy performance standards” to tackle the 15% worst-performing buildings in Europe, is currently being debated by the European Parliament and by member state ministers on the EU Council.

A crucial component of REPowerEU is a separate document titled EU “Save Energy”, which lays out a “two-pronged approach” to cutting energy use through “mid- to long-term energy efficiency measures” and “personal choices”.

Notable proposals for the longer term include a ban of fossil fuel-only heating appliances by 2029 and ending subsidies for fossil fuel-based boilers in buildings by 2025 “as a minimum”.

The commission says states should introduce measures, such as reduced VAT rates for home insulation and heat pumps, to “cushion social and distributional impacts”.

As for people’s personal choices, the commission cites International Energy Agency (IEA) research that suggests behavioural changes could rapidly cut oil-and-gas demand by 5%. The commission also encourages member states to set up promotional campaigns encouraging low energy use, in light of the war in Ukraine.

For the most part, the commission alone does not have the capacity to make member states apply the energy-saving solutions proposed in this plan, meaning political endorsement from EU governments will be important.

What will the new proposals mean for EU fossil fuel use?

The strategy provides mixed messages on fossil fuels, with gas use projected to fall significantly even as billions of euros are invested in new pipelines and coal use falls more slowly than previously expected.

After years of debate around the use of gas as a “transition” fuel to help coal-reliant member states decarbonise – and the controversial inclusion of gas in the EU’s “green taxonomy”, albeit with heavy conditions – the new plan envisages a much smaller role for gas.

“In the new reality, the EU’s gas consumption will reduce at a faster pace, limiting the role of gas as a transitional fuel,” says the commission.

If it were carried out in its entirety, the strategy would yield reductions in EU gas consumption far exceeding its Russian imports.

In 2021, the EU imported 155bcm of gas from Russia, and the commission estimates that full implementation of the existing Fit for 55 package would already have lowered gas consumption by 116bcm, by 2030, equivalent to 75% of current Russian imports.

According to a “working document” released by the commission, higher-than-expected gas prices are expected to reduce use by another 40bcm and REPowerEU measures add an extra 100bcm in cuts over this period.

This would amount to a two-thirds reduction in overall gas consumption from today’s levels and would eliminate demand for roughly twice as much gas as the EU currently imports from Russia

The commission highlights a reduced role for gas in industry, with 35bcm less gas in the REPowerEU analysis on top of the 11bcm in savings from Fit for 55 by 2030 – in total a 63% reduction from current levels.

It says this will require “coordinated action to activate all levers”, including efficiency, hydrogen and electrification, but there are no detailed plans for delivering the goal.

The impact of the new proposals is even more dramatic for gas-fired power, where the fuel is projected to supply 67% less electricity in 2030, relative to what had been expected under Fit for 55.

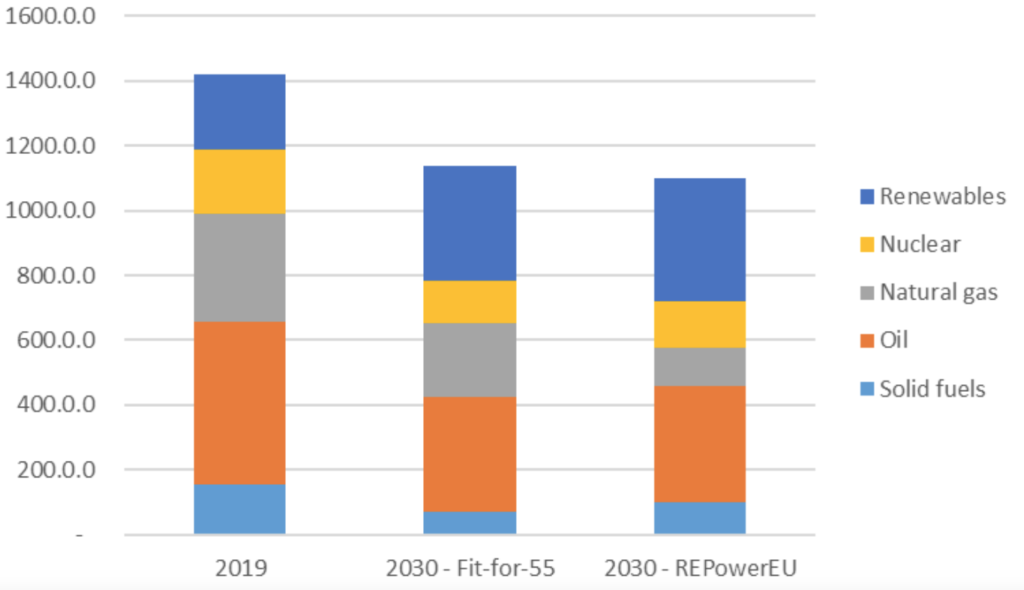

The much smaller role for gas (grey chunks) can be seen in the chart below, which shows overall EU energy consumption in 2019 and in 2030 under two different scenarios – the earlier Fit for 55 plan and the new REPowerEU proposals.

Total energy use in 2030 would be slightly lower, following the higher ambition for energy savings, and there is an increased role for renewables in line with the higher 45% by 2030 target.

However, there is also an increased role for nuclear and oil, as well as coal – the highest emitting fossil fuel. In fact, compared to Fit for 55, in the new scenario gas consumption in 2030 would be 48% lower – but coal consumption would be 41% higher.

Nevertheless, the document states:

“Despite temporarily higher coal use in power generation, the climate ambition levels [of cutting emissions to 55% below 1990 levels by 2030] are reached since REPowerEU leads to investments in renewables and energy efficiency beyond the Fit for 55 proposals.”

The commission says that aiming for higher gas cuts than the volume of Russian imports in 2021 provides some leeway, given imports have at times been even higher. It also notes that aiming high in the shorter term could allow the EU to “roll back” temporary measures before 2027, such as lower thermostat settings, delayed coal phaseout and delayed nuclear phaseout.

With gas consumption set to plummet under the proposals, campaigners criticised the commission’s call for €10bn to support imports of liquified natural gas (LNG) and gas pipelines, and for up to €2bn investment in oil infrastructure.

The commission names gas projects in Poland, Greece and Romania, among others, as potentially being eligible for support, and says member states will be able to apply for financing to support facilities of “European importance”.

This fossil-fuel investment would only be around 4% of the total proposed, but civil society groups expressed concerns about the lifespan of these projects considering the need to phase out gas in the coming years.

“It will be important to ensure that the limited [gas] projects foreseen…do not end up making the case for more long-term infrastructure,” Raphael Hanoteaux, a senior policy advisor on gas politics at E3G tells Carbon Brief.

Civil society groups have argued that if the EU leaned more on renewable energy it could achieve better outcomes in a shorter space of time, without building more fossil-fuel infrastructure.

Analysis conducted by four European thinktanks earlier this year found that the EU could end Russian gas imports by 2025 – earlier than the commission’s target – without the need for new gas infrastructure or increased coal use.

Sarah Brown, an analyst at Ember who led the research, tells Carbon Brief the key difference between their analysis and the commission’s is a more ambitious outlook for solar power.

They used SolarPower Europe’s “accelerated high” scenario, with 400GW and 840GW of solar installed by 2025 and 2030 respectively, roughly 25% more than proposed by the commission in its REPowerEU plan.

Nevertheless, Brown says she is not concerned about a temporary increase in coal use as the fuel remains “incredibly expensive” and countries are unlikely to backtrack on their coal phaseout targets:

“Also, if coal consumption by 2025 is slightly higher than originally anticipated in the Fit for 55 plan due to economic reasons, this will further reduce gas demand and make any new gas import infrastructure even more unnecessary.”

How much will the plan cost?

The REPowerEU strategy has been released at a time of great economic hardship, making the costs involved all the more significant. This situation was recognised by European commissioner for energy Kadri Simson, who told a press conference:

“We recognise that untying Europe from its largest energy supplier is going to be difficult but the economic benefits for ending our dependence are much greater than the short-term cost of REPowerEU.”

The strategy was widely described as a “€210bn plan”. Rather than money from the EU alone, this figure refers to the amount, on top of Fit for 55 investments, that the commission says will be required by the end of 2027 to achieve REPowerEU’s goals.

It is not the total amount, as the commission says a total additional investment of €300bn would be required by 2030 under its plan.

This figure is based on delaying the phaseout of coal and – in France and Belgium – nuclear power. If member states chose not to do this, the costs would be higher, the commission notes.

At the same time, cutting down on fossil fuel use under these plans would come with significant annual savings, including €80bn for gas import payments, €12bn for oil and €1.7bn for coal.

Central to the financing of these plans will be the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), which was originally set up in response to the Covid-19 pandemic to support member states in their economic recovery.

The commission has proposed changes to the RRF Regulation that would allow member states to insert new REPowerEU chapters into their existing plans. They would then be able to access €225bn in unused RRF loans, as well as €20bn in RRF grants generated by selling off EU emissions trading system (EUETS) allowances.

This approach is controversial for two reasons. Most of the money is in the form of loans and some observers have argued that the balance should be more towards up-front grants to help struggling nations pay for clean technology without going into more debt.

As for the grants that are being provided, selling ETS permits is expected to dampen carbon prices, taking pressure off coal plants and potentially leading to more emissions, as well as cutting national revenues from selling permits. Prices have already dropped since the news was announced.

Dr Claudio Baccianti, an economist at thinktank Agora Energiewende, pointed out that “frugal” EU nations, such as Germany, tend to oppose more grants from the EU, yet such grants may be needed if the commission’s ambition is to be met. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The open question is how EU countries with little fiscal space will be able to finance their public green investment gaps of around 1% GDP per year, net of EU funds, without more EU solidarity.”

Will the EU’s new plans support international climate efforts?

Alongside the main REPowerEU plan, the commission also released its EU external energy engagement strategy, marking the first update to the bloc’s international energy diplomacy strategy since 2015.

Maria Pastukhova, a senior policy advisor working on energy diplomacy at E3G told Carbon Brief at a recent conference that in a low-carbon future, Europe would still be highly dependent on other countries – for example, for critical raw materials from China:

“But we are talking about a much more resilient energy system where industry is not [going to be] crushed…just because Russia stops supplying gas.”

Seen as an opportunity to match the domestic ambition of the EU’s climate goals on the world stage, the new international plan was greeted with disappointment by civil society groups. They criticised a lack of focus on partnerships based around renewables and critical raw materials.

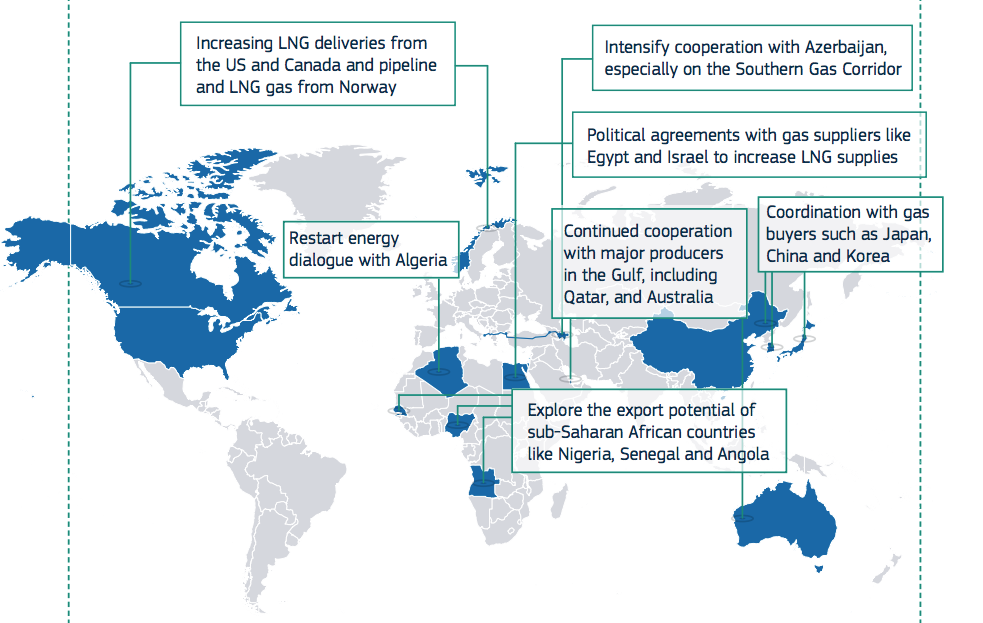

Instead, the strategy mainly addresses access to non-Russian fossil fuels, including increasing LNG deliveries from the US and Canada, and coordinating gas purchases with large Asian countries. Key focal areas can be seen in the map below.

As a first step in “diversifying energy imports”, the main REPower plan notes that the EU energy platform has already been established to help member states pool resources to access gas, LNG and hydrogen. This has begun with a “regional taskforce” involving Bulgaria, which has already seen its gas supply disrupted by Russia.

Inspired by the success of the common Covid-19 vaccine purchasing programme, the plan mentions plans for a “joint purchasing programme” to negotiate better deals for member states on fossil-fuels imports. It also proposes a similar programme for hydrogen.

The strategy references new links with African nations that it says “offer untapped LNG potential”, a move that faced criticism from activists. Among them are nations such as Nigeria and Angola, where roughly half the population lack access to electricity.

There was also criticism of the plans to establish fossil-fuel ties with Azerbaijan, Israel and Qatar, all nations linked with human rights abuses.

The document’s main focus on international clean energy comes from plans for “major hydrogen corridors” to facilitate the target for 10m tonnes of imported green hydrogen via the Mediterranean, the North Sea and, “as soon as conditions allow”, Ukraine.

Finally, the strategy includes plans to support the energy systems of nations “facing Russian aggression”, including Ukraine as well as eastern nations, such as Moldova and Georgia.

How does this link to the EU’s wider climate strategy and targets?

The EU is currently in the process of hashing out its Fit for 55 proposals, which were only proposed by the commission 10 months ago and are still going through a lengthy legislation process. They are set to be voted on by the European Parliament in June.

This package, which already includes increased targets for renewables and energy efficiency, among other things, is designed to enable the bloc to hit its goal of a 55% cut in emissions from 1990 levels by 2030, paving the way for net-zero by 2050.

In theory, the ambitious new REPowerEU targets, if delivered with Fit for 55, could result in emissions cuts that exceed the 55% target. This is hinted at in the strategy, which says it “will have a positive impact on EU’s emission reduction over the decade”.

However, this would depend first of all on Fit for 55 being delivered in its entirety – something that is not assured as it has yet to pass through parliament and be approved by member states.

On top of this, for REPowerEU to become reality, parliament and member states would have to take the commission’s recommendations for new legislation and integrate them into the on-going policy negotiations.

Elisa Giannelli, a senior policy advisor at E3G, tells Carbon Brief that while the new strategy increases the chances of going beyond the 55% target, “many unknowns remain”. However, she adds:

“Recent votes in the European Parliament are already sending positive signals about the MEPs’ willingness to increase the sectoral targets and accelerate the Fit for 55 implementation.”

As for the non-binding proposals and recommendations in the package, these will be at the discretion of national governments. “It is important to note that political pressure on EU leaders is high,” Giannelli adds.

Frans Timmermans, the EU’s executive vice president and climate commissioner, gave a measured response regarding the emissions impact of the plan during a press conference:

“We use natural gas…less in the transitional phase which means that you might use coal a bit longer. That has a negative impact on your emissions. But if at the same time, as we propose, you rapidly speed up the introduction of renewables…you then have the positive movement and so on balance, I hope, we will have even a plus in terms of our emissions reductions. I do not expect us to end up with more emissions, on balance.”

The strategy says that “the fast phasing out of fossil-fuel imports from Russia will affect the transition trajectory, or how we reach our climate target, compared to that under previous assumptions”.

Timmermans also stated that the commission intends to work on modelling to establish more precisely what impact the plan would have on emissions, as requested by member states.

-

In-depth Q&A: How the EU plans to end its reliance on Russian fossil fuels