Avoiding temperature ‘overshoot’ reduces multiple climate change risks, say scientists

Ayesha Tandon

11.29.21Ayesha Tandon

29.11.2021 | 4:05pmAllowing global temperatures to temporarily “overshoot” end-of-century targets will drive greater economic loss and more severe climate impacts than staying below these targets throughout the century, new research says.

Many future pathways for meeting the 1.5C and 2C warming targets by 2100 project that global temperatures will exceed these goals in the short term – and that negative emission techniques will be used later in the century to ensure that targets are met.

However, two new studies published in Nature Climate Change highlight the benefits of meeting global temperature goals outright.

The first study finds that staying below 1.5C or 2C throughout the 21st century reduces the risk of climate extremes, such as heatwaves. The authors find that after mid-century, temperature overshoot leads to higher mitigation costs and greater economic losses from the additional climate impacts.

The second study highlights the longer-term economic benefits of keeping below temperature thresholds. It projects that by 2100, global GDP will be up to 2% higher in scenarios that avoid overshoot compared to those that do not.

These “valuable” papers “give important insights on the consequences of emission pathways without large net-negative emissions during the second half of the century”, says a commentary article on the new research papers.

Temperature overshoots

Since the Paris climate deal was agreed in 2015, scientists have been exploring different “pathways” of future emissions and how they can keep global temperatures to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, or “well below” 2C, by the end of the century.

Many of these pathways rely on a combination of overshoots and “negative emissions” – also known as carbon dioxide removal (CDR). These include measures to enhance the natural carbon sinks – such as afforestation, reforestation and the conservation of degraded marine and coastal habitats. They can also include technologies such as direct air capture, in which CO2 is removed from the atmosphere, or bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, in which bioenergy crops are grown and then burned for energy, and the resulting emissions stored underground.

In these scenarios, the planet continues to warm over the coming decades as humanity works towards net-zero emissions, rising above global temperature targets around mid-century. Then in the second half of the century, the large-scale deployment of negative emission techniques is used to take global temperatures back below the targets.

These future pathways are typically simulated using Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), which combine physical, economic and social data, and can be used to explore climate policy options. The two new studies use nine different IAMs and two types of pathway to explore future scenarios for meeting the 1.5C and 2C warming targets by the year 2100.

The overshoot pathway – referred to as the “end-of-century” pathway in these studies – features relatively high emissions at the start of the century that lead to a temperature overshoot, which is corrected using negative emissions technologies before the end of the century.

Meanwhile, in the non-overshoot pathway – referred to as the “net-zero” pathway – emission reductions are more immediate and temperatures stay below the global temperature goals throughout the century.

Dr Daniel Johansson – an associate professor in the department of space, Earth and environment at Chalmers University of Technology – has penned an accompanying News & Views article on the two new studies. He writes that net-zero pathways are more expensive in the near term, as they involve stronger mitigation, but “will leave us better off in the long-run since we avoid costly net-negative emissions in the future”.

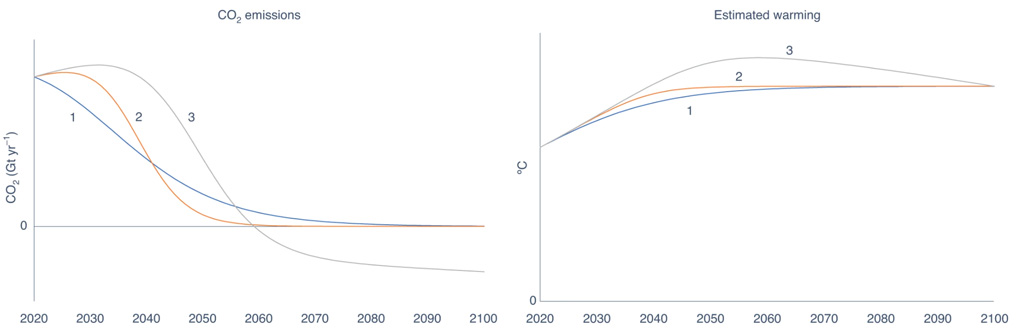

His piece includes an illustration of three different pathways, as shown in the plot below. Lines one and two (blue and orange) are net-zero pathways, while three (grey) is an end-of-century pathway. The plot shows emissions (left) and estimated warming (right) from the three pathways. The slower pace of mitigation in the end-of-century pathway sees greater warming around the middle of the century.

Dr Katsumasa Tanaka is a senior researcher at the Université Paris-Saclay and was not involved in either study. He tells Carbon Brief that there have been criticisms levelled at end-of-century pathways for their reliance on largely “unproven” negative emission techniques:

“This type of scenario has been criticised because of the implicit but very strong reliance on unproven large-scale negative CO2 emissions in the scenario. My 2018 paper in Nature Climate Change… shows that this has led to an overemphasis on the need for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions to achieve the Paris temperature target, because net-zero greenhouse gas emissions are, in a sense, in-built in peak and decline scenarios.”

Meanwhile, Johansson explains in his piece that “the large majority of previous studies” have focused on end-of-century scenarios. He adds:

“Not a moment too soon, the valuable papers by Riahi et al and Drouet et al give important insights on the consequences of emission pathways without large net-negative emissions during the second half of the century. This research will be directly applicable for political discussions on near-term emission targets and their consistency with long-term temperature goals.”

Worsening climate impacts

Dr Laurent Drouet is a scientist at the European Institute on Economics and the Environment and the lead author of the first study. He tells Carbon Brief that IAMs often do not account for the added cost of extra climate impacts in overshoot pathways:

“IAMS do not account for the geophysical and economic impacts from climate change in the design of mitigation pathways; their primary focus is the mitigation costs. This is one of the reasons why many low-carbon scenarios rely on large-scale deployment of negative emission technologies.”

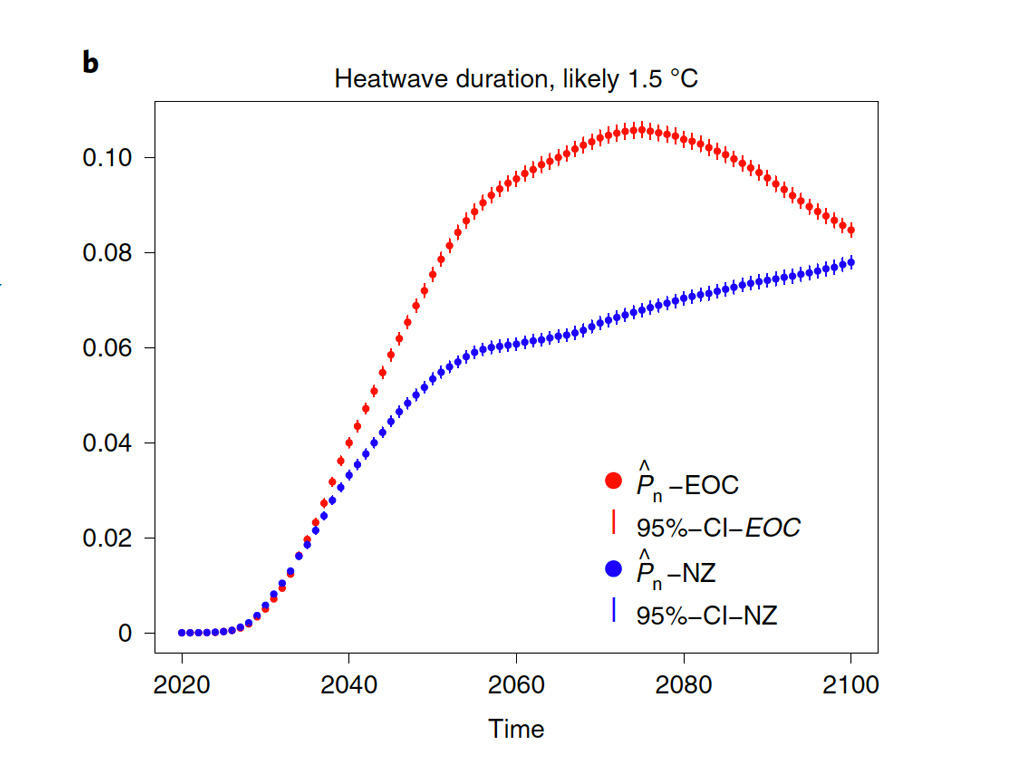

The team calculated the probabilistic climate impacts of a range of indicators – including the frequency and duration of heatwaves and agricultural drought – in both the end-of-century and net-zero pathways to 1.5C and 2C warming.

The biggest differences are seen in heatwave metrics, with Brazil, west and southern Africa the most strongly affected by the worsening heatwaves. The plot below shows the probability of exceeding “high” levels of heatwave duration globally, with the end-of-century scenario shown in red and the net-zero scenario in blue.

The paper highlights that in the end-of-century pathway, the probability of “high” heatwave duration rises are “significantly” larger than the net-zero pathway after 2040.

The study also explores the economic benefits of avoiding an overshoot. The authors use estimates of the relationship between temperature variations and GDP growth to look at the country-level impact of warming on GDP. They find that net-zero pathways “brought more climate economic benefits or avoided more damage” than end-of-century pathways – adding that after mid-century, temperatures overshoot leads to both higher mitigation costs and economic losses from the additional climate impacts.

“The paper is novel in the way IAM results are used for quantifying climate impacts,” Johansson says in his piece. Drouet adds:

“This is the first time that a systematic analysis of the geophysical and economic climate risk of detailed low-carbon scenarios has been carried out, bringing together the forces from the [Working Group II] and the [Working Group III] of the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change].”

Economic loss

The second paper also explores the economic cost of overshooting on global temperature goals.

The study finds that limiting warming to 1.44-1.63C above pre-industrial temperatures without overshoots requires society to reach net-zero emissions by 2045-65. Meanwhile, allowing overshoots means that net-zero does not need to be reached until 2060-70, but that the planet will warm by an extra 0.08-0.16C by the end of the century, according to the study.

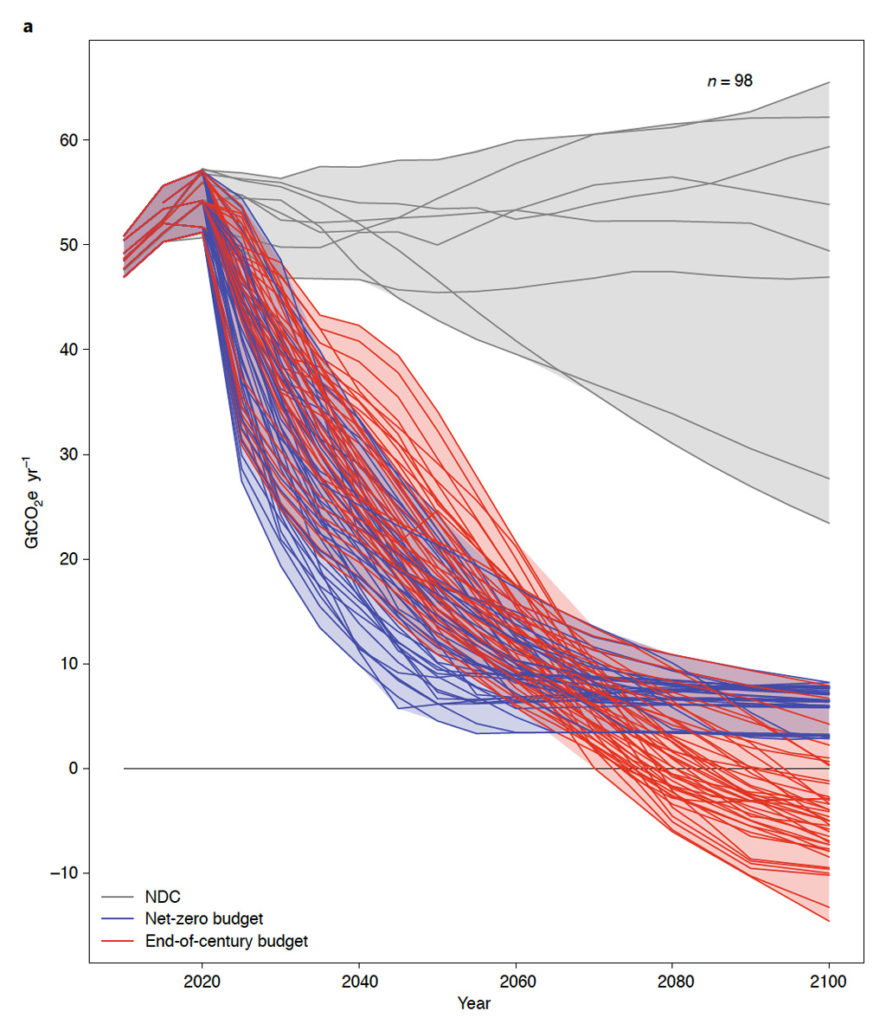

The authors also assess current progress towards the 1.5C and 2C targets. Dr Keywan Riahi is the programme director at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and lead author on the study. He tells Carbon Brief that the 1.5C target is “infeasible” under current emission reduction pledges from individual nations (known as nationally determined contributions, or NDCs):

“We show that the current NDCs will make reaching 1.5C infeasible and would make it economically more costly to achieve 2C. In order to keep options open for limiting warming to 1.5C we need to reduce emissions way beyond the NDCs to between 20-35 GtCO2e [billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent] (which is about 10-20 GtCO2e lower than where the NDCs would leads us in 2030).”

The plot below compares simulated future annual global emissions under existing NDCs (grey) compared to a 2C warming scenario – both with (red) and without (blue) an overshoot.

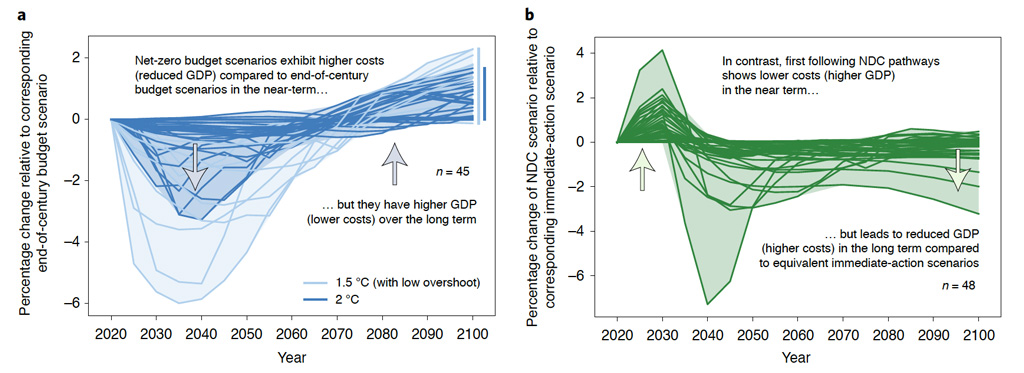

This study also looks in more detail at the economic benefits of avoiding an overshoot. It finds that upfront investments will limit temperature overshoot and bring long-term economic gains – adding that global GDP in 2100 will be up to 2% higher in scenarios that avoid overshoot.

The plots below show the cost incurred in net-zero scenarios compared to the cost of end-of-century scenarios, measured using GDP. The plot on the left (blue) shows the cost for 1.5C and 2C scenarios, while the plot on the right shows the cost from NDC scenarios.

In scenarios that avoid an overshoot, the authors find that mitigation is required more rapidly in the short-term, requiring higher upfront costs. However, they add that the economy can rebound once net-zero is achieved, leading to higher GDP growth in the second half of the century than in scenarios with a temperature overshoot.

Tanaka highlights that, according to the study, the higher near-term GDP losses of limiting overshoot are fully compensated by higher GDP growth in the second half of the century:

“What strikes me the most is that…GDP [in 2100] will be higher under net-zero scenarios than under end-of-century scenarios. This is a very interesting (and, to my knowledge, new) finding that supports net-zero scenarios from the mitigation point of view.”

The study also finds that the difference between overshoot and net-zero scenarios is more notable in more stringent temperature targets. Riahi adds that the study highlights the need for CDR even in scenarios without overshoot:

“A key result of the study is the importance of CDR beyond negative emissions. Even in a net-zero system without any net-negative emissions, you need CDR to offset emissions from sectors that are hard to abate. And you can use CDR also to accelerate near-term emissions reductions and thus reduce peak temperature.”

Tanaka tells Carbon Brief that he is “pleased” to see the authors of this study focusing on net-zero scenarios, which is “a step forward to explore scenarios without significant temperature overshoot”. However, he adds two points to consider:

“First, the analysis stops at 2100. This comes from how the IAMs are set up, but leaves it open what happens to the scenarios after 2100. There may be a rebound of GDP for the end-of-century scenarios after 2100, which is not however captured by the current analysis.

“Second, it has been claimed that mitigation actions bring more economic growth. I have not dug into this claim and I do not know this is considered in the IAMs, but I wonder how this might influence their outcome.”

Drouet et al (2021), Net zero-emission pathways reduce the physical and economic risks of climate change, Nature Climate Change, doi:10.1038/s41558-021-01218-z

Riahi et al (2021), Cost and attainability of meeting stringent climate targets without overshoot, Nature Climate Change, doi:10.1038/s41558-021-01215-2

-

Avoiding temperature ‘overshoot’ reduces multiple climate change risks, say scientists

-

New research shows benefits of meeting global warming limits without ‘overshoot’