Q&A: How will China’s new carbon trading scheme work?

Jocelyn Timperley

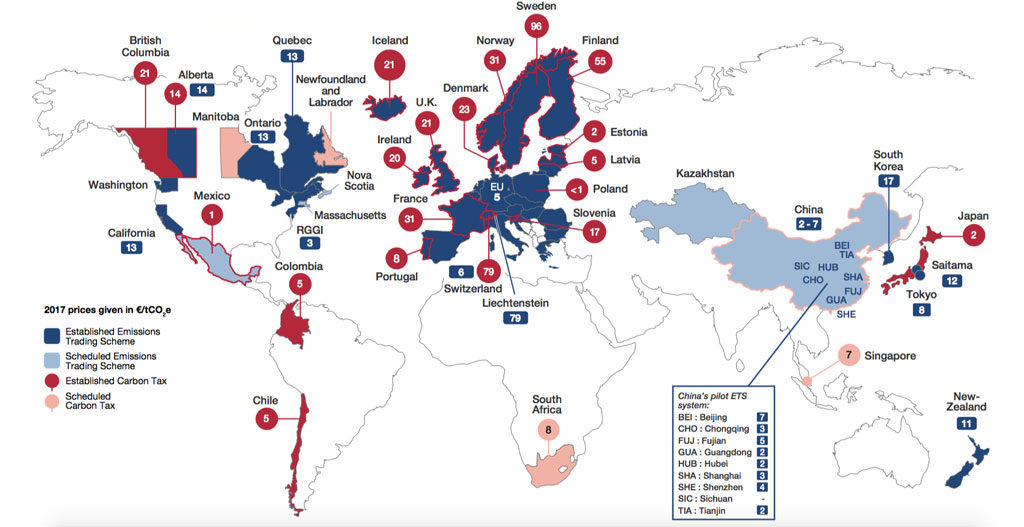

01.29.18Last month, China announced the initial details of its much-anticipated emissions trading scheme (ETS).

The launch confirmed China’s plans to move to a national carbon market, following several years of regional pilots projects.

The new scheme will have a more cautious rollout than set out in initial draft plans, starting with the power sector alone in a national pilot phase.

However, it will still be by far the world’s largest carbon market.

Carbon Brief takes an in-depth look at what is known about China’s ETS, the remaining gaps and how it will fit in with China’s wider climate policy landscape.

How did China’s ETS come about?

China’s greenhouse gas emissions are the highest in the world and are estimated to have risen by around 4% last year, halting several years where they flatlined. It burns more coal than the rest of the globe put together.

Alongside other policies to cut emissions, China has long had plans to create a national carbon market. First floated in the country’s 12th Five-Year Plan in 2011, plans to roll out a nationwide scheme in 2017 were confirmed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in a US-China joint climate statement in the run-up to the Paris climate summit in 2015.

In January 2016, a notice to industries set out the steps they should take to prepare for the national scheme. This notice was circulated by China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the state agency tasked with developing the ETS. Draft plans covering three sectors were then set out for consultation with industry and other government departments in May 2017.

On 19 December 2017, China released an initial framework for the first nationwide phase of the ETS, just inside the deadline set by the president’s 2015 pledge. This was the first document with final approval by the state council, the country’s chief administrative authority. (Note that Carbon Brief is relying on an unofficial translation of this framework plan, published by crowdsourced translating website China Energy Portal).

Initially set to cover more than 3bn tonnes of CO2 from the power sector, the carbon market will be the largest in the world and close to double the size of the next largest, the EU ETS. Once operational, it will mean around a quarter of global CO2 emissions are covered by carbon-pricing systems.

In developing its plans, China has reportedly been very conscious of the issues affecting other emissions trading schemes. It has conducted extensive discussions with representatives from schemes in California and the EU, in an effort to learn from their mistakes.

According to Jeff Swartz, director of climate policy and carbon markets at the South Pole Group and previously director of international policy at the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), these include the need to have good emissions data and to set a conservative emissions benchmark from historical data. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The government in China has studied this clearly: there are traces in the plan to make sure the cap is set appropriately. They have understood the mistakes in Europe.”

Li Gao, the NDRC’s director, has explicitly said China is not considering linking its ETS with other countries at this stage, adding that it will also take time to have a national carbon price.

According to the New York Times, China’s ETS could serve as a laboratory for other carbon markets developed in the future. If it manages to implement an effective carbon price, it could also reduce fears in the EU of carbon leakage to China.

Will the ETS help China hit its climate targets?

Environmental policy has become a priority in China, in part due to widespread concerns over air pollution and climate change caused by cars and coal-fired power plants.

China’s government has begun to put a strong emphasis on curbing CO2 emissions. The country plans to spend $363bn on renewable power capacity by 2020 and has a leading presence in renewables investment abroad. It has also moved to cap its coal capacity, ban petrol and diesel cars (albeit without a firm date), increase industrial energy efficiency and improve air quality.

Its climate pledge ahead of the Paris Agreement included a goal to peak CO2 emissions by “around 2030”, and make “best efforts” to peak earlier. It also plans to source 20% of its energy by 2030 from non-fossil sources (this stood at 13% in 2016). Other goals include a decrease in the carbon intensity of its economy and an increase in forest stock volume.

China is already set to overachieve on its aim to peak emissions by 2030, according to Climate Action Tracker (CAT). However, CAT also notes that these targets are far from being in line with the Paris Agreement, which commits countries to limit global warming to well below 2C and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5C.

China’s trading scheme, therefore, comes in the context of a wide range of climate policies. One 2016 comparison of the potential for 35 environmental policies in China to drive down emissions found carbon pricing would be the most effective.

However, with little confirmed about how it will work (see below), it is hard to judge its possible impact.

Li Shuo, an energy and climate policy analyst for Greenpeace East Asia, tells Carbon Brief the real question is how much the country will overachieve its goals and if the ETS plays any role. As is the case for the EU ETS, there will be debate over whether the China ETS itself drives emissions reductions, or merely mops up after all the other related policies.

For example, Swartz says coal plant closures will result from other regulations. He says:

“The ETS is a transitory policy tool that sends a market signal for companies and investors to shift away from heavily polluting sources.”

Max Dupuy, senior associate at the Regulatory Assistance Project, says other policies may have more of an influence on carbon emissions in the near term, as the ETS develops over time. He tells Carbon Brief:

“There are a lot of things that are going on and they all have interlocking effects and they will, in turn, interact with the emissions trading scheme.”

What will be covered by the trading scheme?

Perhaps the most significant part of the announcement in December was that it scaled back the sectors the ETS would cover.

Early plans for the scheme, circulated in January 2016, had included firms consuming more than 10,000 tonnes of “coal equivalent” in eight sectors: petrochemicals, chemicals, building materials (including cement), iron and steel, non-ferrous metals (such as aluminium and copper), paper and civil aviation. This would have covered around 6,000 companies.

However, the December launch confirmed that only the power sector will be included at first. Plants emitting more than 26,000 tonnes of CO2 per year or more – covering almost all coal and gas-fired plants – will be included, the government plan says. This will still almost double the amount of emissions worldwide covered by emissions trading schemes.

The scheme will, therefore, only involve around 1,700 power companies at first. This will be gradually expanded “when conditions allow…to other industries with high energy consumption, high pollution and high resource intensity”, the plan says. It is expected to eventually include the other seven sectors previously proposed.

Swartz argues this vastly diminished ETS, compared to the original plan, is the big story of the release in December, arguing it “won’t have any bite in it” with the power sector alone. He tells Carbon Brief:

“After studying the market for years and conducting pilots, how much delay do you need when you know what needs to be done?”

Emissions have already levelled off in China’s power sector, while even with the other seven sectors included the ETS would by no means cover all of China’s emissions. Swartz estimates it would reach perhaps half of China’s CO2 emissions because key emitting sectors are excluded, including land transport and agriculture.

Others have argued it is important for China to move cautiously and take the time to get the emissions trading scheme right, with the power sector a reasonable place to start.

For example, policymakers need reliable data on historic baseline emissions from different plants, to set the right target levels and allocate allowances. Some observers have noted that the large state-owned enterprises that dominate electricity generation in the country have relatively complete emissions data, at least compared to other parts of the economy.

Chinese officials have similarly expressed concern that including other sectors at the outset would require constant testing and adjustments, given they are still in the process of establishing their emissions datasets.

The typically large size of power plants, which might emit tens of millions of tonnes of CO2 each year, also means relatively few points of emissions compared with other industries.

In an article for Vox, David Roberts argues the key thing to remember is that China’s government thinks long term. He writes:

“The most important thing is getting the baselines, rules and procedures right, creating a functioning system that can be used as a ratchet for decades to come.”

The plan itself says China wants to avoid “affecting…stable and healthy economic development” by including too many industries at the outset.

How will China’s carbon market work?

Carbon markets aim to provide incentives for polluters to reduce emissions by allowing firms to trade the right to emit. In the EU and California, this has involved putting an absolute cap on emissions, which is reduced over time.

However, China has generally resisted setting absolute emission caps in its climate pledges, instead opting for intensity-based targets to cut emissions per unit of GDP. While the precise methodology for the cap-setting in China’s national carbon market has not yet been released, government sources have indicated it will take a similar approach.

Therefore, it appears China will use a rate-based limit for its ETS. This would see a limit put on the amount of CO2 allowed per unit of output. Each power company would be allocated a certain number of credits, depending on how much electricity it produces. If it emitted less than this set quota, it could then sell that surplus to another firm.

This would reward firms for producing less emissions per unit of output, rather than less emissions overall, which could help alleviate political worry about constraining economic growth. But it would mean that even if power producers become more efficient, emissions could in theory still rise, if power production increases overall.

Who will pay for emissions?

In an initial “simulated” trading period of the ETS, companies will be issued free emissions permits. Under the plan’s loose timeline, auctions for permits would begin around 2020.

Once payments begin in the power sector, it is companies that would foot the bill, not consumers. This is because power prices are set by government regulators in China.

However, a process to reform electricity pricing in China (see next section), already underway for several years, could allow the carbon price to be passed on to consumers in future. Dupuy tells Carbon Brief:

“There’s still quite a way to go before we can say that the power sector’s been reformed and transformed to a model where the true costs, including emissions costs, are really flowing through to end users.”

Prices for other industries are set by the market rather than government regulation, so once the ETS expands outside the power sector, it could have an impact on consumers.

How will the ETS affect the power sector?

In theory, carbon pricing should encourage a switch from higher emitting power sources, such as coal. While prices in the EU have generally been too low to achieve this, the contribution of a carbon price to the rapid fall in coal-fired power in the UK shows it is possible.

If China does set a rate-based limit of allocating permits rather than an absolute cap, this would mean the setting of benchmark emissions rate per unit of output from each fuel.

It also appears the scheme may set different benchmarks for different parts of the power industry, depending on the size of the producer and type of fuel used. This would mean coal-burning plants would only compete against each other, rather than against cleaner gas plants.

Some experts have warned this means the ETS would struggle to move electricity consumption towards cleaner sources. Zhang Junjie, director of the Environmental Research Center at Duke Kunshan University, told the South China Morning Post:

“The focus will be on improving efficiency of existing plants, rather than improving the energy structure by replacing coal with gas or other cleaner energy sources.”

Lauri Myllyvirta, a clean air and clean energy expert working with Greenpeace in Beijing, similarly says an intensity-based allocation would not encourage a cleaner fuel mix, but could help to push power plants to increase their efficiency. Myllyvirta tells Carbon Brief:

“Improvements in thermal efficiency are much easier to predict than the combination of electricity demand, mix of energy sources and thermal efficiency. Of course, this would at the same time mean that the role of emissions trading in China’s overall climate efforts is more limited than if an overall [emissions] cap was set.”

Myllyvirta points out, however, that even if such an intensity-based method is used, it is not known whether this would just be the approach for an initial period, or more permanently.

In addition, even if the ETS makes polluting plants more expensive, it may not affect their “dispatch order”. Unlike most other jurisdictions, China does not traditionally change the order in which its power plants are turned on based on their operating costs. Dupuy tells Carbon Brief:

“That means, effectively, that one of the normal channels through which we’d expect to see emissions trading work is not functioning well in the current power system in China.”

The power sector reform effort currently underway in China could address this, says Dupuy. First launched in 2015, this is perhaps the most overlooked of the country’s other climate policies. It promises to address each of the major “pain points” for clean energy and could have far bigger implications for China’s emissions than the ETS. Dupuy tells Carbon Brief:

“One of the major thrusts of the power sector reform is for each of the generators to compete, based on its relative operating costs and relative efficiency, for the number of hours that they’re going to operate on an hour-by-hour, day-by-day basis.

“These new markets should allow the power sector to be more flexible, to be more efficient, and to transmit the cost associated with carbon in a more fluid way to users throughout the system.”

The process of developing this reform is long. While China has a commitment to get to national competitive electricity markets by 2020, Dupuy says he is not sure if this timetable will be met. However, some progress has already been seen.

In the meantime, a shift to cleaner energy may also be driven by China’s other power sector targets, such as goals for the increasing the share of low-carbon sources in the energy mix, and coal plant closures driven by other regulations.

What will happen to China’s pilot ETS projects?

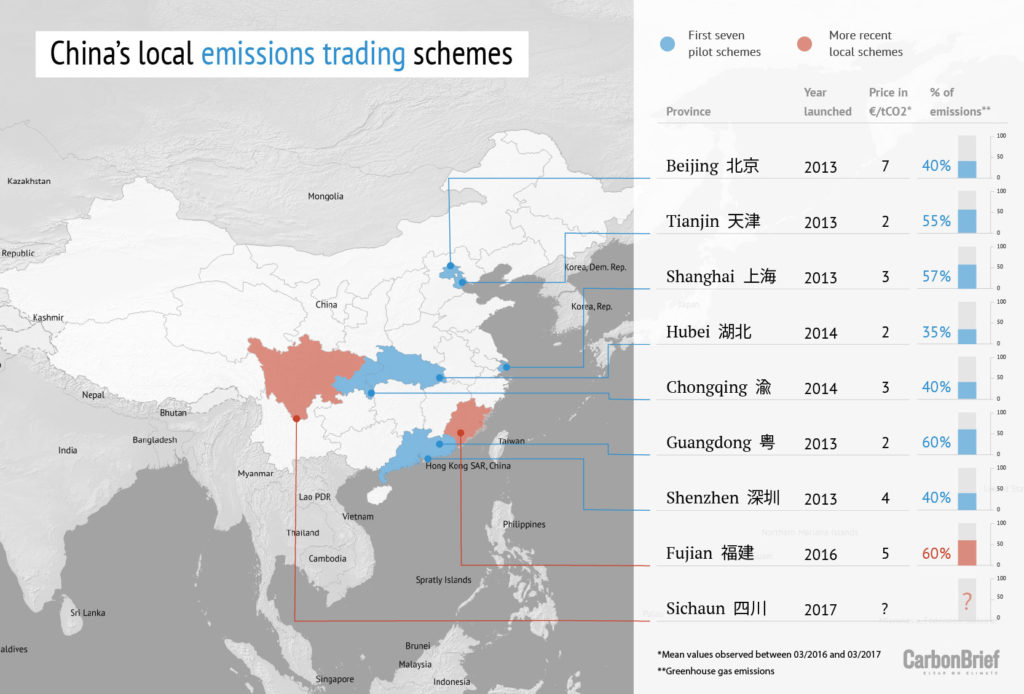

China launched regional pilot carbon trading projects in four cities, two provinces and the special economic zone of Shenzhen during 2013 and 2014. Two more local schemes were launched in 2016 and 2017 in Fujian, a southeastern Chinese province near Taiwan, and Sichuan in southwest China, although these are not usually counted as pilot schemes.

The locations of these nine local schemes are shown in the map below.

The initial seven pilots were developed by local governments with intentionally different designs, to help inform the development of the national scheme. They cover more than 3,000 firms in a variety of sectors depending on the scheme, including power, steel, cement and aviation.

As shown in the map above, the pilots cover 35%-60% of greenhouse gas emissions in each region. Compliance with the various rules of the pilots is reportedly high.

The schemes have run into some issues, however, including a lack of transparency and a low trading volume. One criticism has been that they have mainly avoided using financial derivatives, such as futures trading. Some argue this has made the markets ineffective in providing a clear price signal for big emitters. However, some of the pilot regions are now experimenting with such mechanisms.

According to Paula DiPerna, special adviser with CDP North America, the seven pilot programmes have allowed China to “legitimise” the concept of cap-and-trade. She told Bloomberg:

“China had 10 years to train people and let them learn the ropes of carbon trading. They were a de facto university for a generation of emissions-market traders. The rest of the world has pretty much lost a decade.”

The pilots have also allowed the government to test how trading systems could work with very different profiles. For example, says Swartz, the cities generally have high emissions in the buildings and transport sectors, while in Hubei province, the largest emissions source is iron and steel.

Leaders have emerged among the pilots, helping to establish best practices for the national market, according to ChinaDialogue. Guangdong province and Hubei have experimented with auctioning allowances, for instance, Swartz tells Carbon Brief, while the Beijing market has maintained the highest and most stable carbon price.

As of the beginning of 2017, these covered around 3,000 sources, with total annual CO2 emissions of 1.4bn tonnes.

Prices averaged $2.27/tonne, according to the Partnership for Market Readiness, an international platform backed by the World Bank to foster carbon markets instruments. For comparison, over the past five years EU ETS emissions allowances have hovered between €4 and €9 ($5-11) per tonne, itself well short of most estimates for the social cost of carbon.

Jiang Zhaoli, deputy head of NDRC’s climate change department, has said companies will not feel real pressure to cut emissions until the carbon price hits 200-300 yuan/tonne ($31-47/tonne). He added that he does not expect this to happen until after 2020.

Transaction values since the pilot schemes began reportedly reached around 4.5 billion yuan ($706m) in September last year and the value of trades in the pilots has been rising over time. However, this is far below the €49bn ($61bn) of allowances or their derivatives that were traded in the EU ETS in 2015 alone.

Power-sector emissions now under pilot schemes will shift into the national ETS, once it is launched. The pilot projects will continue for sectors not yet included in the national carbon market, such as chemicals, oil and gas. China’s plan says these will gradually be moved into the national scheme “when conditions allow”.

When will the ETS start?

The government plan released in December is hazy about the exact timeline for the rollout of the ETS. Instead, it sets out the next few stages of implementation and makes clear that any and all parts of this plan could be adjusted.

In the first stage, over the next year or so, China will focus on the basic infrastructure of the scheme: setting up emissions monitoring, reporting and verification systems, alongside the administrative aspects of the trading system. Companies will be required to monitor and report their emissions to the NDRC and other relevant local regulators.

Power companies will start to receive ETS allowances in this time and the legal basis for the ETS is also likely to be strengthened, according to Energy Foundation China.

The second step will be a year-long “simulated” trial of the market, the plan says, expected to start in 2019. This will see free credits allocated to companies with mock trading, but with no money changing hands. It aims to test and develop the reliability, market risks and management of the trading platform, the plan says.

(Update 13/2/2019: In November 2018, a senior Chinese government official working on climate said the country still has a lot of work to do before it can fully launch the scheme nationwide. China will gradually phase in the system that is already running behind schedule, he added. Early signs indicate China is taking an “extremely cautious approach” that is likely to put off real emissions reductions until “well into the next decade,” according to a June 2018 article in the MIT Technology review.)

Only after these two year-long steps will trading for money begin in the power sector. Since the plan says the two earlier stages will take around a year each, this is unlikely to happen until at least 2020, although China has set no concrete date.

It is worth noting that 2020 will be a key year for China, when it is set to release both its next Five-Year Plan and its updated Paris pledge.

If the power-only carbon market reaches “stable operation”, the plan says this is to be followed by a gradual expansion of the market to include other sectors, as well as other tradeable products, such as emissions offsets. However, there is no timeline for either of these.

How will trading work under China’s ETS?

Once trading begins on the national market in 2020 or so, it appears China plans to conduct it using spot trading: regular trading between firms on a carbon trading exchange. This excludes the use of financial derivatives such as carbon futures trading, the mechanism by which companies can speculate on the market by buying and selling the right to future permits at guaranteed prices.

Xie Zhenhua, China’s special representative for climate change, ruled out carbon futures trading in November, saying China’s scheme is intended to create a cost for emitting carbon rather than a platform for market speculation.

Sophie Lu, an analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance in Beijing, told Bloomberg in December:

“After several false starts and shifting priorities and nervousness around whether or not carbon speculation will make policy enforcement difficult, the regulators have decided to be even more cautious about the market deployment.”

Swartz is among those who say carbon futures trading should be included in the scheme. He tells Carbon Brief it would create additional liquidity in the market and allow a real carbon price to emerge. He notes that China is exploring the use of futures trading and will likely first start with a pilot carbon futures trading system in one region before allowing it across the entire ETS.

What don’t we know about China’s ETS?

Many more of the details and outcomes of China’s national carbon market remain uncertain. As well as the lack of firm dates for rollout and expansion to other sectors, other key details about the scheme have also yet to be clarified.

Carbon price

Perhaps foremost among these is the question of the price companies will have to pay for emissions, once the market is established in 2020 or so. Prices have been low in the pilots, and with the mechanisms and processes for allocating or auctioning credits still unclear, it is hard to say if and when a price large enough to put pressure on emissions will emerge.

The issuing of too many permits due to regulators anticipating higher emissions than actually occur could lead to low prices and a loss of confidence in the market. This has been a significant problem in the EU’s carbon market, which is still struggling to correct low prices caused by a massive surplus of allowances.

However, handing out permits on an intensity basis could make it easier to avoid over-allocation if coal power output is much lower than expected, Myllyvirta from Greenpeace tells Carbon Brief.

It is also worth noting that the scheme will be implemented relatively fast, compared to the others schemes, such as in the EU where companies had more notice. Zou Ji, the president of Energy Foundation China, an NGO, told the New York Times that China is likely to issue many credits at first and then gradually tighten annual allocations to force up the market price. However, China has not yet set this out.

Free vs paid allowances

There has been no word on what proportion of allowances will be distributed for free and how many will be sold at auction. Details on how permit auctions might work are also scarce.

Among other things, this will determine the extent to which the China ETS will generate any revenue, which could go to funding additional climate change programmes.

Disclosure

In its 13th Five-Year Plan, covering 2016 to 2020, China said it will develop a greenhouse gas emissions information disclosure system. However, this has not yet been implemented.

The success of the ETS will depend on such disclosure of corporate information, write Kate Logan and Ma Yingying from the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), a Chinese thinktank, in an article for ChinaDialogue.

According to IPE analysis, none of China’s seven official ETS pilots have yet disclosed carbon emissions data for key polluting firms, which contributes to major price volatility by limiting the ability of markets to predict carbon prices. Logan and Yingying write:

“In fact, there is no publicly available information on how much CO2 an emissions trader has emitted, or whether or how their emissions data are verified.”

Swartz also argues that disclosure will be important to the nationwide scheme, for example, by revealing the business case for the use of low-carbon technologies in a sector low on credits.

Verification of data will also be important. Myllyvirta and Shuo warn that the initial allocation of free permits could create incentives for companies and provincial governments to inflate their output or emissions projections, for example.

Speaking to Bloomberg earlier this month, Paula DiPerna from CDP said the market has to be as credible to traders as any other commodity market, in order to create a carbon price that “remotely corresponds to the cost of mitigation”.

Penalties

It is also unclear whether there will be any fines or penalties for non-compliance with the scheme in its various stages.

Dimitri de Boer, vice chairman of the China Carbon Forum, a non-profit working on climate change, says the central government is likely to learn from experiences of enforcement under the pilot schemes, where compliance has been high, as it rolls out the national ETS. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The pilot systems have had various types of enforcement measures, including fines, penalties in the form of additional compliance obligation for the following year and public announcement of non-compliance…We hope that there will be adequate transparency regarding the compliance of companies.”

Offsets

While China has created an offset standard, the rules and future of this in the new ETS are not yet clear.

The May 2017 draft plan discussed offsets as a flexibility provision. The new national ETS plan says trading will be expanded to other tradable products, such as voluntary emissions reductions “when conditions allow”.

These so-called “voluntary emission reductions” would allow non-industrial carbon reduction projects, not covered by the ETS, to sell credits to companies obliged to take part, Huw Slater, a researcher at China Carbon Forum, tells Carbon Brief.

According to Swartz, many companies that develop offset projects are not investing until this is clarified. This is important, he argues, as the absence of offsets means additional incentives will be needed for areas such as reforestation and tackling refrigerant gases that also warm the climate.

This article was updated on 15/2/2019 to include comments from a senior Chinese government official on the status of the ETS.