Biomass subsidies ‘not fit for purpose’, says Chatham House

Jocelyn Timperley

02.23.17Jocelyn Timperley

23.02.2017 | 8:45amSubsidies should end for many types of biomass, a new Chatham House report argues, because they are failing to help cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The report adds that policymakers should tighten up accounting rules to ensure the full extent of biomass emissions are included.

The analysis outlines how policies intended to boost the use of biomass are in many cases “not fit for purpose” because they are inadvertently increasing emissions by often ignoring emissions from burning wood in power stations and failing to account for changes in forest carbon stocks.

It argues that UK and recently revised EU rules for bioenergy are inadequate for managing and monitoring the emissions from burning biomass.

Carbon Brief examines the main arguments of the report, which cut through the long-running debate about the climate impacts of burning biomass.

Contentious issue

The rising demand for renewable power around the world has led to a large increase in the production and burning of wood pellets. Advocates, such as power firm Drax – the UK’s largest biomass user – argue they are more reliable for providing baseload power than other renewables, such as wind or solar.

Worldwide production hit a record 28 million tonnes (Mt) in 2015, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), up from under 20Mt just three years earlier. Meanwhile, the UK has become the world’s largest importer of wood pellets, burning 42% of the 15.5Mt of total global imports in 2015.

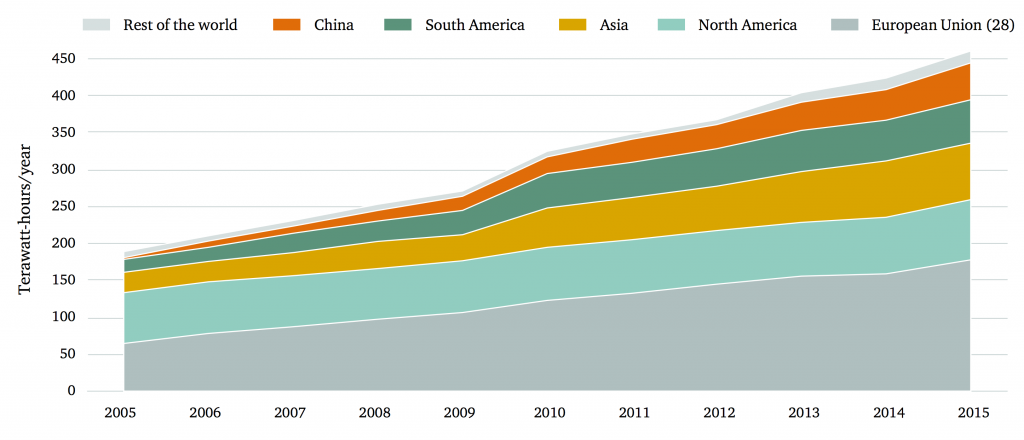

The chart below shows how global electricity generation from biomass, which includes wood pellets, more than doubled between 2005 and 2015.

Biomass-fired global electricity generation, by country/region, 2005–15. Source: United Nations Environment Programme (2016). Graph by Chatham House

As the chart shows, the EU is now the world’s biggest user of biomass for electricity generation. Bioenergy is expected to contribute 57% of the EU’s total renewable energy by 2020.

Following calls for the EU to introduce better safeguards for biofuels, a revised legislation proposal in the latest EU energy package in December introduced new sustainability criteria for bioenergy production.

These included new rules aimed at ensuring forests are harvested sustainably and conservation areas are protected. It also established new thresholds for how much greenhouse gas emissions need to be saved by switching to biofuels.

However, the Chatham House report argues that even countries who have already begun to apply these new criteria largely fail to include changes in the levels of forest carbon stock in their calculation of greenhouse gas savings.

The report attacks two underlying assumptions which are used to classify biomass as “carbon neutral”. It argues financial and regulatory support should only be given to biomass feedstocks which cut carbon emissions in the short term – which it says is not the case for most of the woody feedstocks used for biomass energy.

Wood for trees

The first assumption is that since trees absorb carbon as they grow, forest growth will balance the carbon emitted by burning wood for energy. For example, the methodology specified in the 2009 EU Renewable Energy Directive for calculating emissions from biomass only considers supply-chain emissions and counts combustion emissions as zero. Several national frameworks including the UK’s also make this assumption.

However, the reality of the situation is more complicated, the report argues. (See this Carbon Brief investigation for more.) The overall emissions from burning trees will depend on a variety of factors, including the type of woody biomass used, what would have happened to it if it had not been burnt for energy, and what happens to the forest from which it was sourced.

For instance, the report argues harvesting whole trees to burn as wood pellets will nearly always results in more emissions than using fossil fuels instead, since the trees will no longer sequester carbon as they grow and soil carbon can be lost during the harvesting. This is particularly the case for older trees, which sequester more carbon than younger trees.

The so-called “carbon payback period” – the time it takes for regrowth of the forest to reabsorb the emissions from biomass – also becomes important here. In a context where climate tipping points could be crossed in the short term, as some evidence suggests, increasing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, even for a few decades, becomes relevant.

The report suggests only biomass energy with the shortest carbon payback periods should be eligible for financial and regulatory support. The feedstocks which are most likely to reduce net carbon emissions would be primarily mill residues and post-consumer waste.

In addition, since woody biomass is less dense and contains more moisture than fossil fuels, burning wood for energy usually emits more greenhouse gases per unit of energy produced than fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, supply-chain emissions from harvesting, collecting, processing and transport all play a role in the total climate impact of biomass feedstocks. The report says:

“Overall, while some instances of biomass energy use may result in lower life-cycle emissions than fossil fuels, in most circumstances, comparing technologies of similar ages, the use of woody biomass for energy will release higher levels of emissions than coal and considerably higher levels than gas.”

Some types of biomass feedstock which do not require extra harvesting – such as sawmill residues or black liquor – can be carbon-neutral at least over a period of a few years, the report adds. This is especially likely if these are burnt on-site as this will reduce emissions from transport and processing.

However, even for waste feedstocks, it is still important to consider whether they could have been used for other, lower carbon purposes. For instance, mill residues can also be used for wood products, which would keep the carbon trapped in materials, such as particleboard, for several decades more than if it is released into the atmosphere through burning it.

The concerns highlighted in the report are also relevant to bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). This is the leading candidate to provide the negative emissions which are heavily relied on in many pathways to global climate goals, including those for the UK.

If the assumption that biomass is effectively emission free at the point of burning is flawed, then this puts a serious dent in the potential of BECCS providing negative emissions. The report reads:

“The reliance on BECCS of so many of the climate mitigation scenarios reviewed by the IPCC [International Panel on Climate Change] is of major concern, potentially distracting attention from other mitigation options and encouraging decision makers to lock themselves into high-carbon options in the short term on the assumption that the emissions thus generated can be compensated for in the long term.”

International frameworks

The second assumption which leads biomass to be seen as carbon neutral stems from international frameworks for reporting and accounting emissions, such as those used under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol. But these decade-old rules are currently under revision by the IPCC, with the burning of imported biomass for power (as takes place at Drax) already identified as a topic in need of updating.

Calculating CO2 emissions from burning imported biomass is hard/controversial. IPCC is proposing this technical note for its 2019 update pic.twitter.com/gUb8ODiNYA

— Leo Hickman (@LeoHickman) February 22, 2017

In order to avoid confusion or double counting of emissions, these frameworks currently allocate emissions into the land-use sector rather than the energy sector. However, flexibilities in land-use accounting can leave biomass emissions falling through the gaps, counted in neither the country of origin nor where it is burnt. The Chatham House report says:

“This risks creating perverse policy outcomes. Where a tonne of emissions from burning biomass for energy does not count against a country’s emissions target but a tonne of emissions from fossil fuel sources does, there will be an incentive to use biomass energy rather than fossil fuels in order to reduce the country’s greenhouse gas emissions – even where this reduction is not ‘real’ in the sense that it is not accounted for by either the user or the source country.”

The report argues that land-use accounting rules need to be reformed to ensure all parties to the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement include the sector in their national accounting, while counties importing biomass from countries which do not account for the related emissions should account for them themselves.

The report echoes a similar finding from a study conducted last year for the Natural Resources Defence Council by energy specialists Vivid Economics. It concluded that the UK’s use of biomass in power stations is leading in some cases to higher emissions than the coal it is replacing.

The risk of biomass being worse than coal was the subject of a report commissioned by the now-defunct Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). But despite receiving the report in April 2016, the findings have yet to be published.

Subsidies

The Chatham House report is quite specific about how it thinks policy support, principally through subsidies, should be redesigned. It says:

“A more practical approach would be to limit the types of feedstock that can be used, as several EU member states and the US state of Massachusetts already do. The aim would be to restrict eligibility for support to those feedstocks that are most likely to reduce net carbon emissions (or have low carbon payback periods): primarily mill residues, together with post-consumer waste. Fast-decaying forest residues could also fit into this category, but in practice this is small-diameter material that is likely to contain too much moisture and dirt to render it usable by biomass plants; and it would be very difficult for policy to distinguish easily between fast and slow-decaying residues…”

It continues:

“Policies should ensure that subsidies do not encourage the biomass industry to divert raw material (such as mill residues) away from alternative uses (such as fibreboard), which have far lower impacts on carbon emissions. This may require the sustainability criteria to be adjusted from time to time depending on market conditions.”

However Drax insists the biomass it uses is sustainably sourced from working forests where biodiversity is protected, productivity is maintained, and growth exceeds what is harvested. In a statement released in response to the report it says:

“We agree that not all wood should be used for bioenergy. We source from working forests which supply other industries – including construction and furniture making – with high grade timber. We take the low grade material to make the compressed wood pellets used to generate electricity. This includes tree tops, limbs, sawmill residues, misshapen and diseased trees not suitable for other use, as well as thinnings – small trees removed to maximise the growth of the forest. There is a widespread scientific consensus that this low-value wood is precisely the material which delivers the biggest carbon reductions.”

Dr Nina Skorupska, chief executive of the Renewable Energy Association (REA), which represents Drax, adds:

“This report hangs on the fallacy that it takes decades for a forest to recapture carbon. That isn’t true. A well-managed forest is continually growing and it locks in carbon at an optimal rate.

Conclusion

The debate over biomass is unlikely to be resolved soon. The Chatham House report is just the latest analysis to outline how policy support for using biomass as a way to reduce carbon emissions is far more complicated than once thought. It concludes that while the use of waste biomass can in some cases save carbon, much of the biomass obtained from other sources may well not.