IEA: Clean energy transition makes reforms ‘inescapable’ for oil states

Jocelyn Timperley

10.25.18Jocelyn Timperley

25.10.2018 | 12:00amA changing energy system is posing “critical questions” for many of the world’s largest oil and gas producing countries, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says.

The rise of shale gas and oil in the US, global improvements in energy efficiency, and the response to climate change are leading to “sustained pressure” on countries that rely heavily on hydrocarbon revenues, it says.

In a new report, the IEA explores what these changing dynamics mean for six major oil-producing states and the consequences of a global push to meet climate change goals.

Oil producers

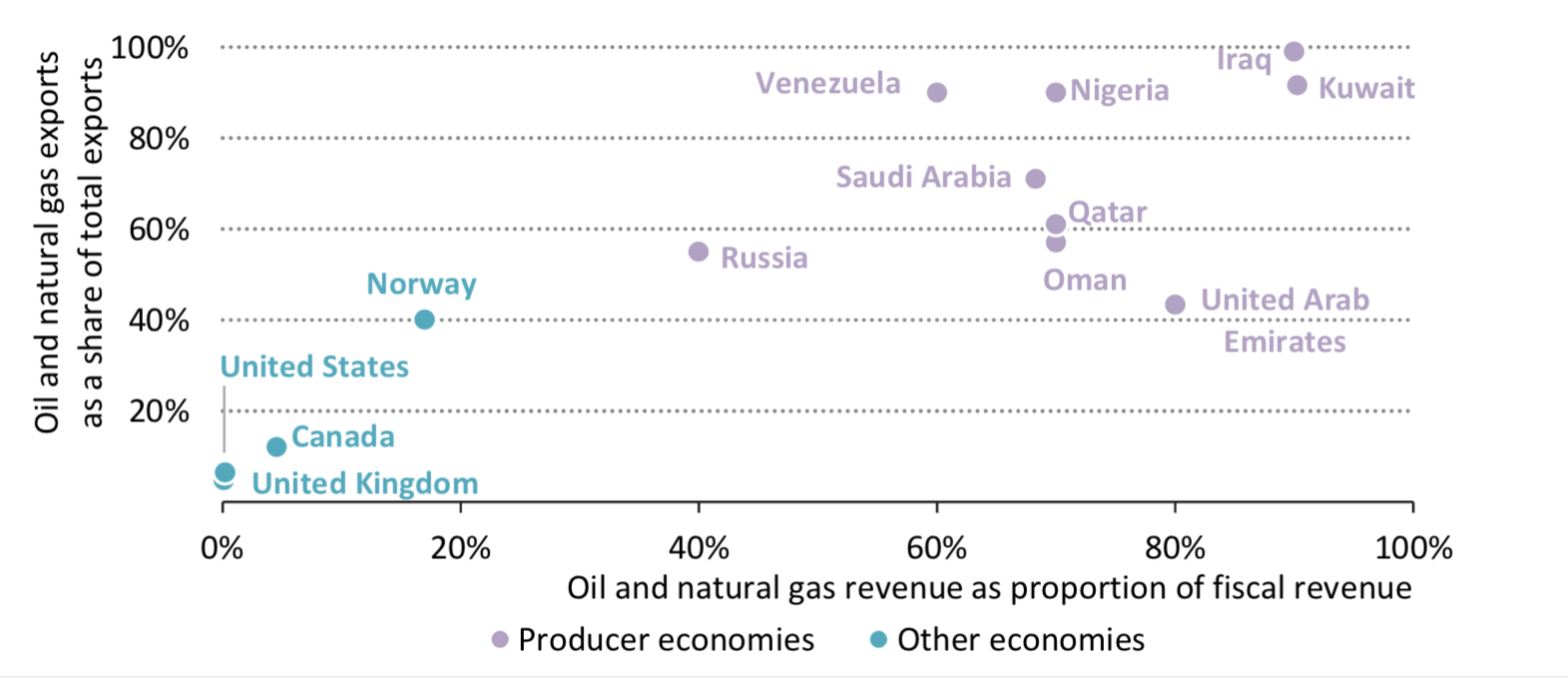

The report focuses on “producer economies”: large oil and gas producers which rely on hydrocarbon exports for a large portion of their national budgets.

Many of these countries are shown (in purple) in the chart, below. The report narrows in on six of these – Iraq, Nigeria, Russia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Venezuela – chosen for their range of circumstances.

Oil and gas exports as a share of total exports (x-axis) and oil and gas revenue as a share of fiscal revenue (y-axis) in selected countries in 2017. Source: IEA Outlook for Producer Economies 2018

In these six countries, between 40% and 90% of government revenues come from oil and gas income. These earnings make up a similar share of the countries’ total exports.

This somewhat precarious position has been exposed by low oil prices since 2014. This has seen many of these countries facing recessions, falling incomes, budgetary deficits and even social unrest.

The “shale revolution” and long-term uncertainty over demand for oil and gas are “intensifying pressures for change” in these countries, the report says. It adds:

“[H]ow these producers respond to a changing policy and market environment is crucial not only for their own future prospects, but also for global energy markets, energy security and the achievement of global sustainable development goals.”

Alternative scenarios

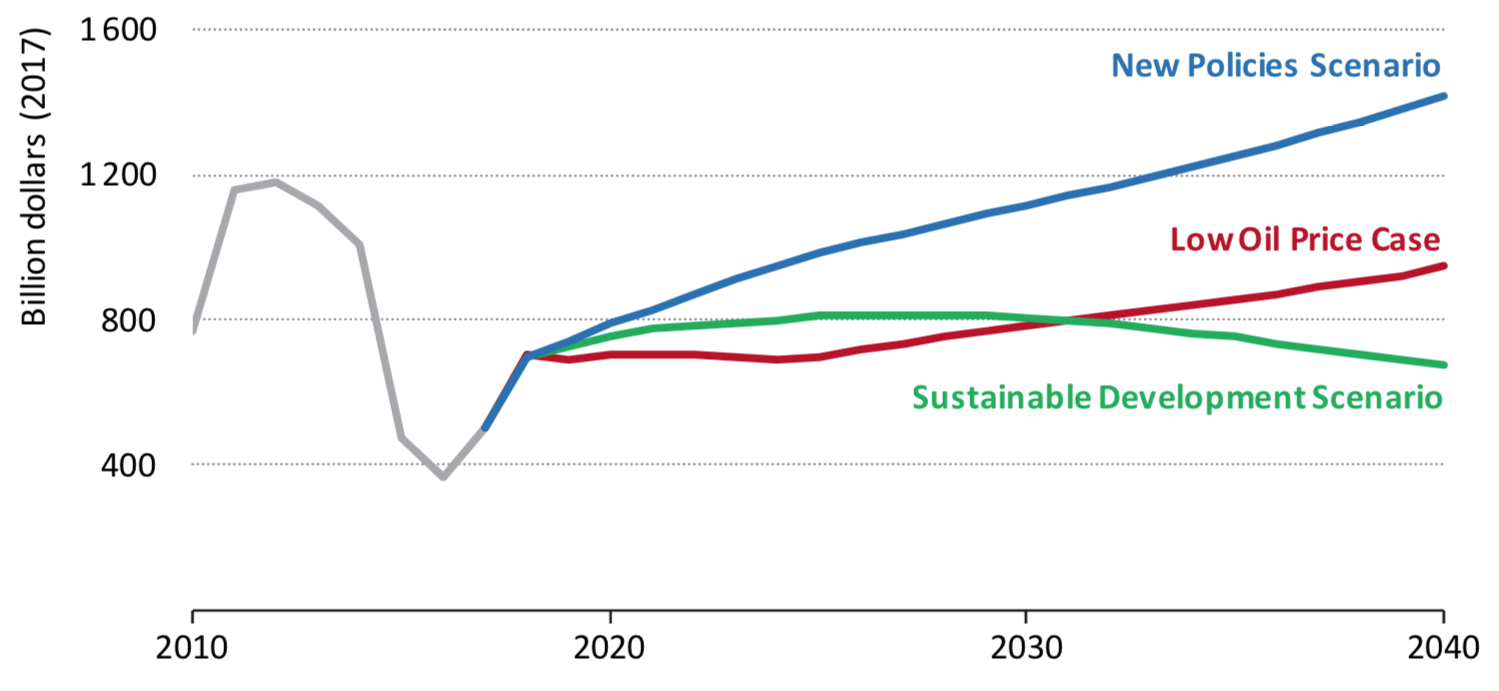

The new report presents three different scenarios for how global oil prices and climate policies will play out over the coming decades. Oil and gas income for the six producer economies is shown in the chart below, under each of the three scenarios.

Average annual net income from oil and natural gas by scenario for six producer economies (Iraq, Nigeria, Russia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Venezuela). Source: IEA Outlook for Producer Economies 2018

The IEA’s main scenario is called “New Policies”. This aims to take a “measured assessment” of where currently announced policies and the evolution of known technologies could take the energy sector up to 2040. [Note that this scenario would breach the climate goals of the Paris Agreement].

Here, despite rapid renewables growth, global hydrocarbon demand and prices rise, particularly as US oil production plateaus in the mid-2020s. Producer economies see far higher revenues from oil and gas than in the other two scenarios.

Even in this scenario, however, the IEA says the arguments for reform remain strong, due to market volatility risk, long-term policy uncertainty and the need to create jobs for large numbers of young people in countries such as Iraq, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia.

In the “Low Oil Price” case, meanwhile, oil prices settle at around $60-70/barrel, and oil and gas income never recovers to levels seen in 2010-2015. A cumulative $7tn is lost up to 2040, compared with the New Policies scenario. The IEA says of this scenario:

“Without far-reaching reforms, this would translate into large current account deficits, downward pressure on currencies and lower government spending. In the Middle East, the downside economic risk equates to a $1,500 drop in average annual disposable income per person.”

In the third “Sustainable Development” scenario, the main energy-related components of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are met and the world remains on track to meet the “well below 2C” goal of the Paris Agreement. Oil demand peaks earlier and gas demand sees lower growth as a result of strong policies on fuel efficiency and fuel switching, as well as rising electric car use.

Oil and gas revenues to 2040 are similar to those in the Low Oil Price case, but the changing circumstances mean producer economies would have “little option but to ready themselves for a world in which hydrocarbons are no longer their main source of revenue”, the IEA says. It adds:

“In this scenario, there is an inescapable imperative to prepare for a world in which hydrocarbons are no longer the main source of revenue, even if…there may be alternative ways to monetise hydrocarbon resources that do not contribute to global emissions.”

Resource curse

Producer economies already tend to be “less diversified and more vulnerable to price shocks” than other economies, the IEA says.

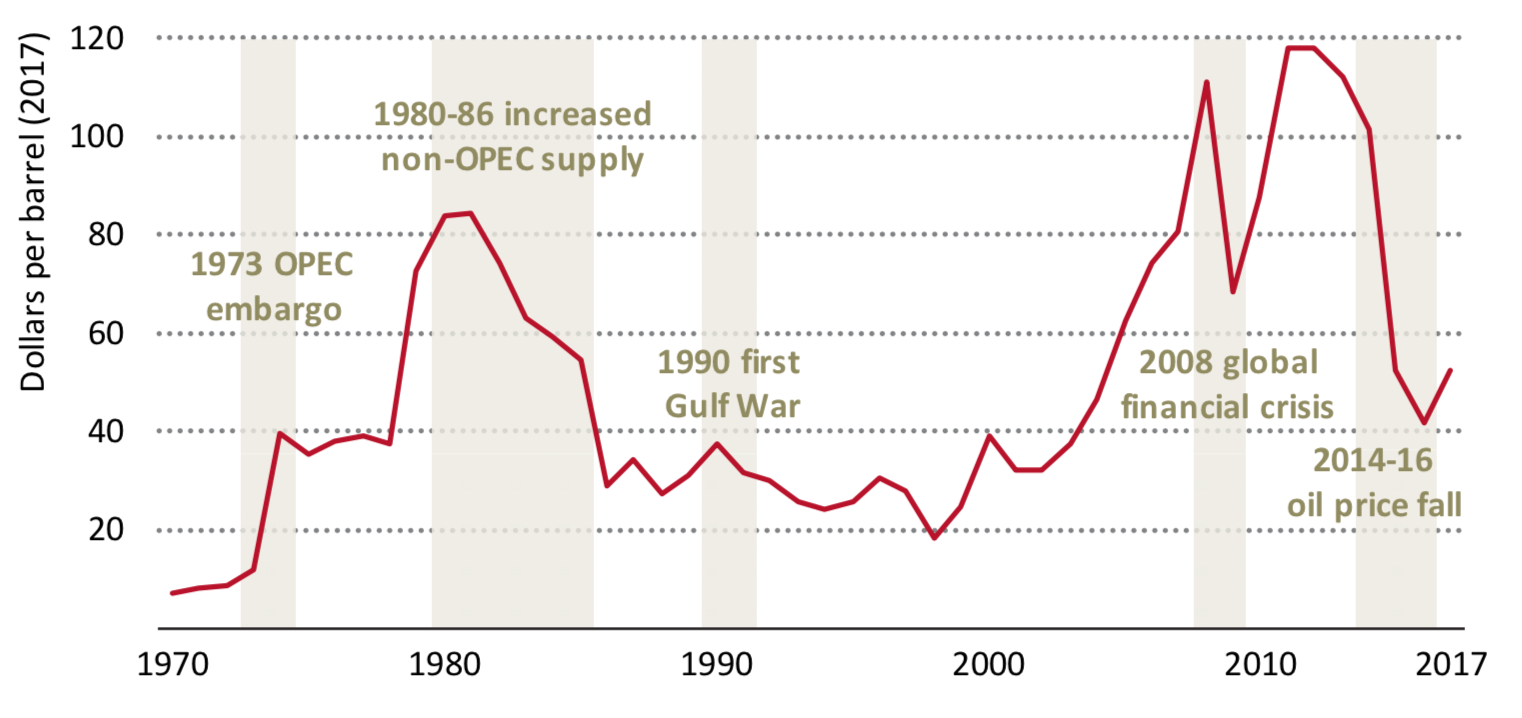

In particular, changing oil prices – shown in the chart below – have brought some structural weaknesses “into sharp relief” in these countries, it says.

Most recently, oil prices started falling in 2014 and saw the steepest decline in the industry’s recent history. Since then, income from oil and gas extraction has fallen by between 40% for Iraq and 70% for Venezuela, with “wide-ranging consequences for economic performance”, says the IEA.

These major swings in revenue can be “deeply destabilising” if finances and economies are not resilient, says the IEA. In a nod to the so-called “resource curse”, it notes that economies which rely on oil and gas exports generally performed less well than non-producers:

“[A]cross a wide range of economies, a ten percentage point increase in the share of oil in exports is associated with relative decline of 7% in long-run per-capita income.”

Wasteful use of energy in producer economies also often contributes to this paradox, the report says. These countries often maintain low prices (compared to the international norm), which can result in higher consumption than elsewhere. In Russia, for example, nearly three times more energy is required to generate a unit of GDP than the world average, the IEA says.

The Russian Druzhba oil pipeline passing through farmland outside the city of Ivano Frankivsk. Credit: Philip Wolmuth / Alamy Stock Photo.

A number of countries have already announced reforms which aim to reduce dependence on volatile oil and gas revenue. For example, Saudi Arabia’s “Vision 2030” aims to increase private sector and foreign investment, cut energy subsidies and increase non-oil government revenue by a factor of six. [Saudi Arabia has also been criticised, however, for pushing for delays in climate action in order to protect its oil revenue].

Some producers have incorporated low-carbon technologies in their diversification strategies: the UAE, for example, plans to source 25-30% of its power from renewables and nuclear by 2030. Traditional oil and gas producers in the Middle East have some of the best solar irradiation rates in the world, the IEA says, and Saudi Arabia and the UAE have seen some of the lowest bids so far seen for solar power projects.

Making use of this huge solar potential and implementing more ambitious energy efficiency policies will be important as Middle Eastern countries try to meet the rapid projected growth in energy demand, particularly for cooling, the IEA says.

Fossil fuel subsidies

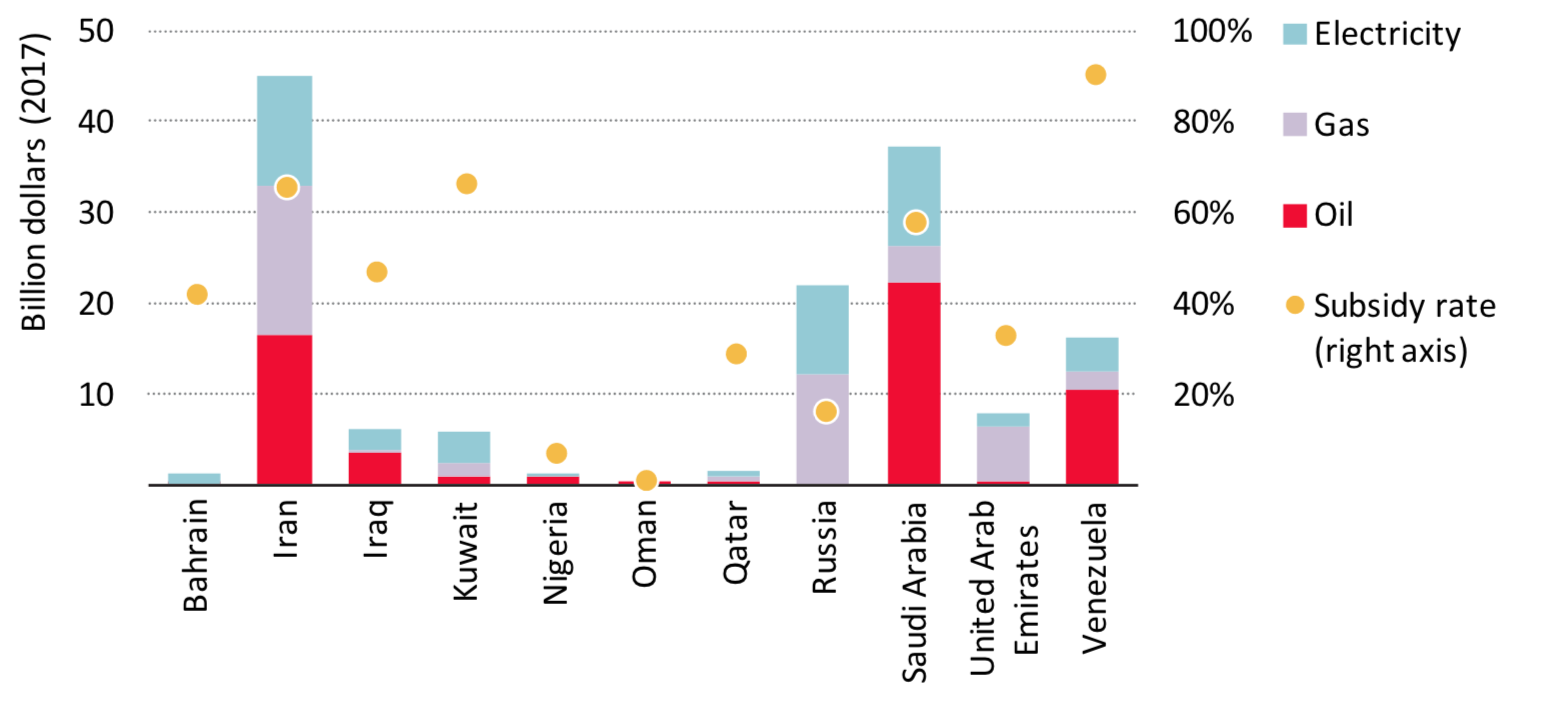

But highly subsidised oil and gas for power generation has so far limited renewables development in the Middle East, the IEA says. The graph below shows subsidies in a range of producer economies.

Estimated value of fossil fuel subsidies in selected producer economies in 2017. The bars show subsidies in $bn while the yellow dots show the subsidy rate (the ratio of the subsidy to the international reference price). Source: IEA Outlook for Producer Economies 2018

Some producer economies have already taken steps to introduce reforms to fossil fuel subsidies, the IEA notes, particularly in light of the fall in oil price from 2014. Iran, for example, has more than doubled the price of regular gasoline since 2010, with plans to invest the extra money in job creation.

The IEA adds that the comparative advantage in energy of major producers will not necessarily disappear during the coming energy transition.

“These countries can produce some of the least costly and least emissions-intensive oil and gas, and could choose to play a leading role in energy technology development, including areas such as carbon capture, utilisation and storage and hydrogen supply.”

-

IEA: Clean energy transition makes reforms 'inescapable' for oil states

-

Fundamental changes ‘unavoidable’ for oil states, says IEA