Mapped: Climate change laws around the world

Simon Evans

05.11.17There has been a 20-fold increase in the number of global climate change laws since 1997, according to the most comprehensive database of relevant policy and legislation.

The database, produced by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the Sabin Center on Climate Change Law, includes more than 1,200 relevant policies across 164 countries, which account for 95% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

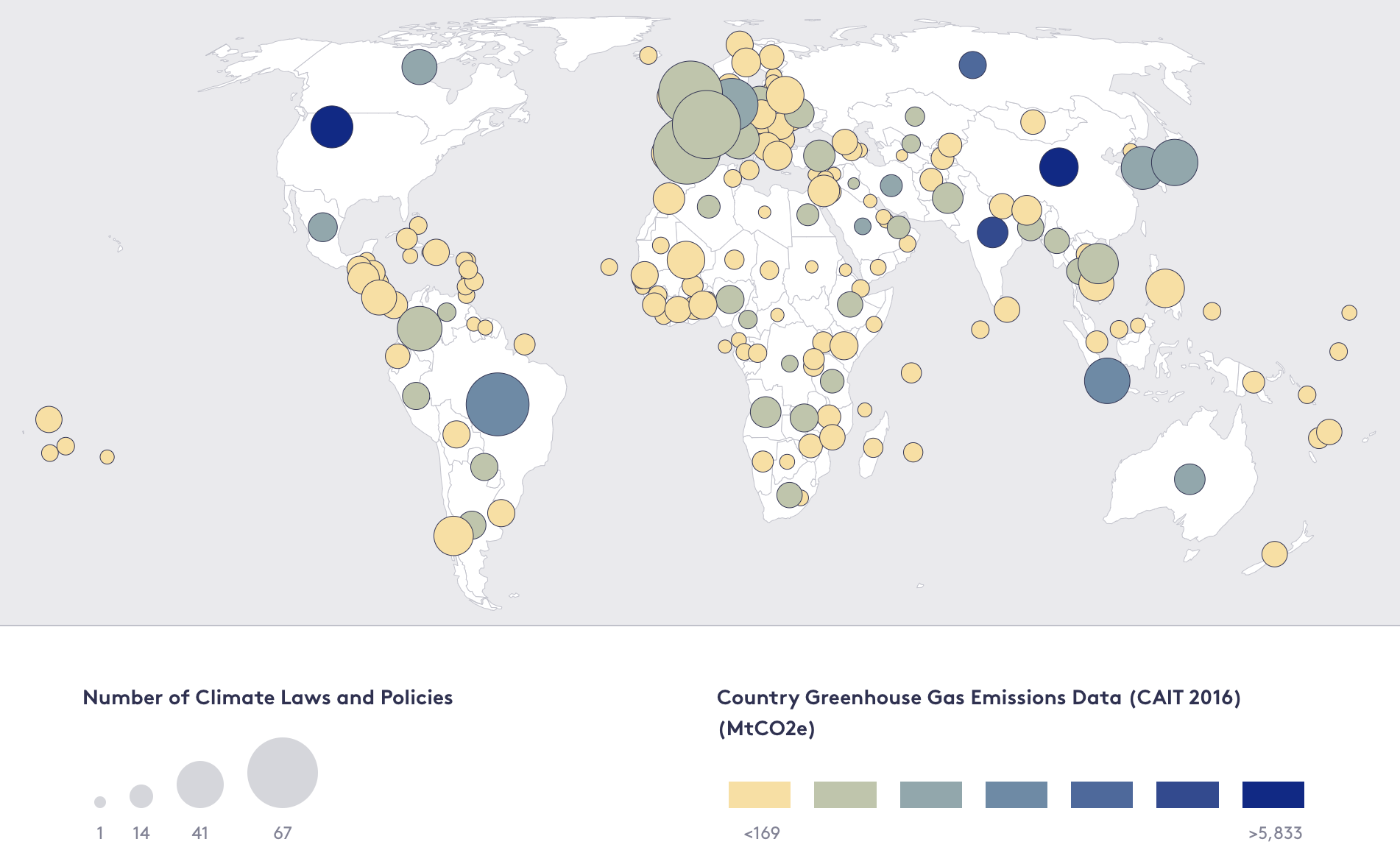

The database shows the extent to which climate change legislation has permeated global political discourse, as well as variations in approach between developed and developing countries. You can explore the database via the interactive map, below.

More laws

For its 2017 update, the sixth edition published since 2010, the climate change law database now covers 164 countries, up from 99 in 2015. This increase primarily reflects efforts to expand the scope of the database, rather than an increase in the number of countries passing climate change laws.

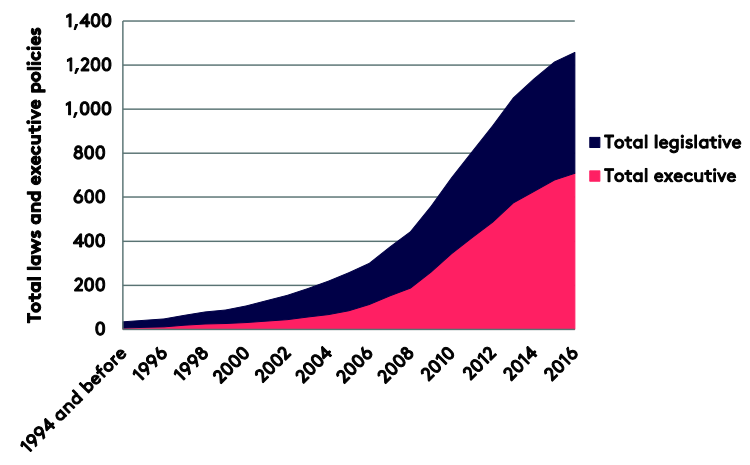

Nevertheless, the number of climate laws continues to grow rapidly. In 1997, the database shows, there were just 60 laws in place, with the figure having risen 20-fold to reach 1,260 today. During that time, the stock of climate laws has doubled every four or five years.

Climate change laws around the world. Legislative laws are passed by parliaments, whereas executive laws or policies are enacted by governments. Source: Global trends in climate legislation and litigation, 2017 update.

The rate of increase in climate laws has slowed since a peak around 2009. This is because most countries now have at least the outlines of their climate policies in place, the 2017 update says. Since the Paris Agreement was sealed in December 2015, another 47 climate laws have been passed, a spokesperson for the Grantham Institute tells Carbon Brief.

Victoria Druce, senior media relations officer for the Grantham Institute, says in an email:

“At the peak of climate law making after Copenhagen [in 2009], there were around 100 per year, at a time when Annex 1 [developed] countries were putting their climate change frameworks in place, which is now done.”

Another issue highlighted by the database is how the world’s Least Developed Countries (LDCs), a bloc of 48 nations that are particularly vulnerable to climate change, are becoming increasingly active on climate change policy.

Whereas developed nations have focused their climate policy on cutting emissions, the LDCs have paid more attention to adaptation. The 2017 update says:

“Reflecting the low carbon footprint of LDCs and their high vulnerability to climate change, the focus of most laws has been on adaptation, but also on building frameworks for promoting and enabling green growth.”

Detailed narratives

As well as the database listing individual laws and policies, there are also narratives for each of the 164 countries covered (you can navigate to these country profiles via the interactive map, above). These detailed pages describe each country’s approach to climate change policy, along with metrics on its emissions, GDP and losses due to natural disasters.

For example, Saudi Arabia’s profile says:

“The Saudi government occupies a difficult position in the debate on climate change. On the one hand, Saudi Arabia has the world’s largest oil reserves and its economy is almost exclusively based on the export of fossil fuels, which are known to be one of the major drivers of climate change. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia with its arid climate is highly vulnerable to the adverse effects of global warming”

It’s worth noting that some of the country narratives in the database are out of date, with the Saudi page dating from November 2015. The US page, for example, was last updated in January 2017, yet makes no mention of President Trump’s efforts to dismantle his predecessor’s climate efforts.

Similarly, South Korea’s page says the country has a target to source 11% of its energy from renewables by 2030. Earlier this week, however, the country elected a new president, Moon Jae-in, who has promised to target 20% renewables by 2030, while moving away from nuclear and coal.

Despite these issues, the database and country pages offer a valuable snapshot of climate policy in almost every country of the world.

Limitations

One thing to note about the climate law database is that it takes a relatively permissive approach to including legislation or policy. This draws in obviously climate-related policies, such as those setting CO2 reduction targets, as well as indirectly relevant laws, for example, company car tax reforms based on carbon emissions.

From a UK perspective, one of the most frequent debates around its climate policy relates to the legally binding nature of its carbon targets. Few other countries, critics argue, have passed similarly stringent climate laws.

Unfortunately, the climate law database does not allow an easy comparison of the bindingness of country approaches to the problem. Carbon Brief has asked the Grantham Institute how many countries have binding climate laws and will update this article once we have an answer.

A 2014 study from the Grantham team compared the UK’s targets to those of its competitors, concluding: “The UK remains a global leader in the way it tackles climate change, but it is by no means acting alone…[It] is part of a leading group of countries taking legislative action to tackle climate change. This leading group includes most of the UK’s main trading partners.”

The study added that China’s target to reduce its emissions intensity (the greenhouse gas emissions associated with each unit of wealth) was “on a par with, and perhaps ever so slightly more ambitious than, the UK’s”.

Two different and more recent approaches to comparing the adequacy and ambition of countries’ climate goals are available from Climate Action Tracker and PWC. The Low Carbon Economy Index, produced by PWC, shows that China is aiming to cut its carbon intensity by 3.5% per year to 2030, whereas the UK’s carbon budget implies cuts of 3.1% per year.

Falling short

Stepping back from the details, one issue highlighted in the 2017 update report is that current climate policies fall far short of what is needed to avoid warming of 2C or more.

In an interview recorded during international climate talks taking place in Bonn this week and next, Prof Sam Fankhauser, one of the researchers behind the climate law database says:

“To reach 2C it’s probably a question of stronger laws, not more laws. Most of the countries we looked at have a framework to deal with climate change, that they have enacted. What we have to do now is to strengthen those frameworks, implement stronger policies, have fewer exemptions, higher carbon prices, more focused support on energy efficiency, better prohibitions on land use.”

You can view the full interview in the video, below.

Did you know there are more than 1200 #climate laws globally? https://t.co/vVqCDpTdBo @SamFankhauser of @GRI_LSE pic.twitter.com/ndDC8NkDJa

— UN Climate Action (@UNFCCC) May 11, 2017

Expanding coverage

The climate law database has evolved since its first edition in 2010, produced by the Grantham Institute in collaboration with the Global Legislators Organisation (GLOBE). Since then, the database has grown in collaboration with the Sabin Centre and the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), the world organisation of parliaments.

In its latest 2017 update, the database now includes 253 climate court cases in 25 jurisdictions, spanning 1994-2016. (Note that these numbers for climate litigation exclude the US, where more than 600 climate court cases are recorded in a separate database.)

In two-thirds of the 253 cases, rulings strengthened or preserved existing laws. Note that, as with the climate law tracker, the database uses a broad scope.

In three-quarters of the cases, climate change is “only at the periphery of the [legal] argument”, the update says. It adds: “Even if climate change is a peripheral issue, the judiciary is increasingly exposed to climate change arguments in cases where, until recently, the environmental argument would not have been framed in those terms.”

Most of these cases (197 of 253) concern particular projects or activities, for example, the licensing of a new coal plant or the allocation of carbon credits under the EU Emissions Trading System. Only 20 call for new laws or policy, or for halts to existing rules. This includes the Urgenda case in the Netherlands, which asked the government to increase its carbon reduction target.

Some 19 of the cases relate to protecting personal property from loss and damage due to climate change. See Carbon Brief’s recent explainer on loss and damage for more on this topic.

Perhaps surprisingly, the most frequent plaintiffs in the climate court cases are corporations, which brought 102 of the 253 legal challenges. NGOs only account for 33 of the cases. Governments are the defendant in 79% of the cases.

In an interview with Carbon Brief earlier this year, Sabin Center director Prof Michael Gerrard, talked about how climate litigation might be used in coming years.

Prof Gerrard told Carbon Brief:

“Another area where I think we will begin to see lawsuits is lawsuits against governments and corporations that failed to prepare for climate change. So, for example, if a building or a bridge or something like that is destroyed, or severely damaged in a storm, and the magnitude of the storm could’ve been and should’ve been foreseen before the building was built, there may be claims against architects, engineers, builders, for not reflecting these foreseeable risks in their designs.”