CCC: Chance of UK meeting climate pledges has ‘worsened’ since last year

Multiple Authors

06.28.23Multiple Authors

28.06.2023 | 12:00amHopes of the UK government meeting its domestic and international climate targets have “worsened” over the past year, according to the Climate Change Committee (CCC).

Its new progress report marks the latest in a series of annual updates, in which the CCC has repeatedly admonished the government for failing to take the action needed to reach its net-zero goals.

It comes in the wake of a High Court ruling that forced the government to provide a far more detailed explanation of how it intends to achieve its legally binding climate targets.

However, rather than setting the nation on a course to hit these goals, the government’s new delivery plan has given the CCC “markedly” less confidence in the UK’s net-zero trajectory.

Last year, it said there were “credible” policies in place to make two-fifths of the emissions cuts needed over the next decade. Now, just one-fifth of those cuts are covered.

Instead, it estimates that existing “credible” climate policies will see emissions flatline – and says only nine out of 50 key indicators are currently “on track”.

Among other things, the UK needs “radical reforms” to its planning policies, controls on the expansion of airports and support for the decarbonisation of heavy industry, the CCC concludes.

In recent weeks, the government has dismissed the opposition Labour party’s plans to end new oil-and-gas licences in the North Sea and described Keir Starmer’s party as being in league with “eco-zealots at Just Stop Oil”.

Yet the CCC states explicitly that “expansion of fossil fuel production is not in line with net-zero” and that, while the UK will still need some oil and gas in the coming years, “this does not in itself justify the development of new North Sea fields”.

- Global context

- ‘Worsening’ policy gap

- Road transport

- Buildings

- Industry

- Fossil fuels and hydrogen

- Electricity

- Agriculture and land use

- C02 removal

- Aviation and shipping

- Waste and F-gases

Global context

The CCC’s progress report follows the release of the government’s Carbon Budget Delivery Plan (CBDP) in March 2023.

The plan set out the government’s approach to meeting its legally binding carbon budgets and was released as part of a deluge of more than 3,000 pages of documents, after the previous net-zero strategy was ruled unlawful.

The updated strategy included plans and policies sufficient, according to the government’s own modelling, to deliver 97% of the emissions cuts needed to meet the sixth carbon budget, covering 2033-2037.

In its report, the CCC says it welcomes the additional detail included within the CBDP and associated documents. However, it says that it has nevertheless become less confident that the UK will be able to meet its legally-binding goals. (See: ‘Worsening’ policy gap.)

The country’s status as a climate leader is slipping, adds the CCC, driven by a number of key factors including a “wan[ing]” commitment to act since the UK’s presidency of COP26 ended and “hesitation” over key parts of government strategy.

The government response to the fossil fuel price crisis – which provided the backdrop for last year’s progress report – did not embrace the “rapid steps that could have been taken to reduce energy demand and grow renewable generation”, the CCC notes.

Moreover, the CCC says the government has “backtracked” on its fossil fuel commitments over the past year, including with the consenting of a new coal mine in Cumbria and support for new oil and gas production.

This is in spite of the “careful wording” of the Glasgow Climate Pact that the government helped negotiate, the committee adds.

(In a recent factcheck, Carbon Brief examined the impact of banning new North Sea oil and gas licences, a policy supported by the outgoing CCC chairman Lord Deben, whilst the progress report notes that the expansion of fossil fuel production is not in line with net-zero ).

In addition, the UK is yet to truly react to the US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s proposed Green Deal Industrial Plan, according to the progress report.

It says the $370bn Inflation Reduction Act will support the development and adoption of low carbon solutions, and has triggered a “green arms race”.

These have provided a “strong pull for green investment away from the UK”, notes the CCC.

Collectively, these elements signify how the UK has lost climate leadership over the past year, the CCC says, even as for many “2022 was the year that climate change arrived” in the form of worsening climate impacts.

The report notes that it was one of the six warmest years on record and the warmest year on record for the UK, with temperatures passing 40C for the first time.

Beyond the UK, floods devastated Pakistan, killing more than 1,700 people and displacing eight million, heatwaves in China led to a drought in the Yangtze River Basin, and an estimated 20,000 people across Europe died of heat-related deaths, the CCC notes.

‘Worsening’ policy gap

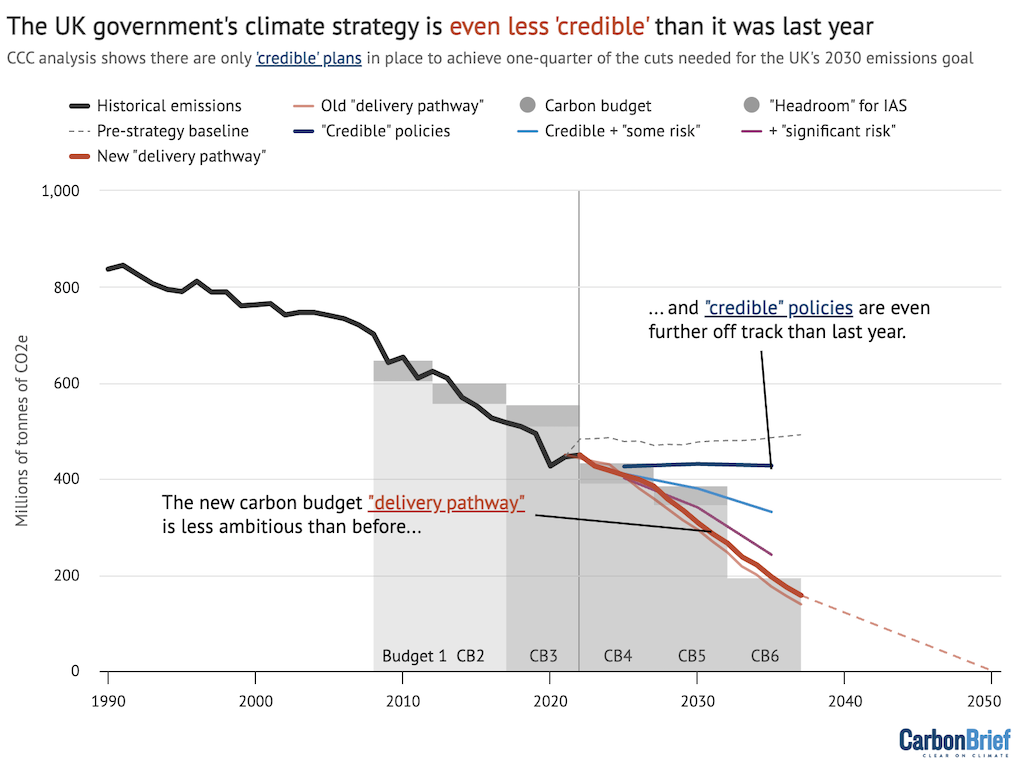

The government’s new delivery plan provided a “welcome and significant increase in detail and transparency”, but ultimately “worsened” the outlook for the UK meeting its longer term emissions targets, according to the CCC.

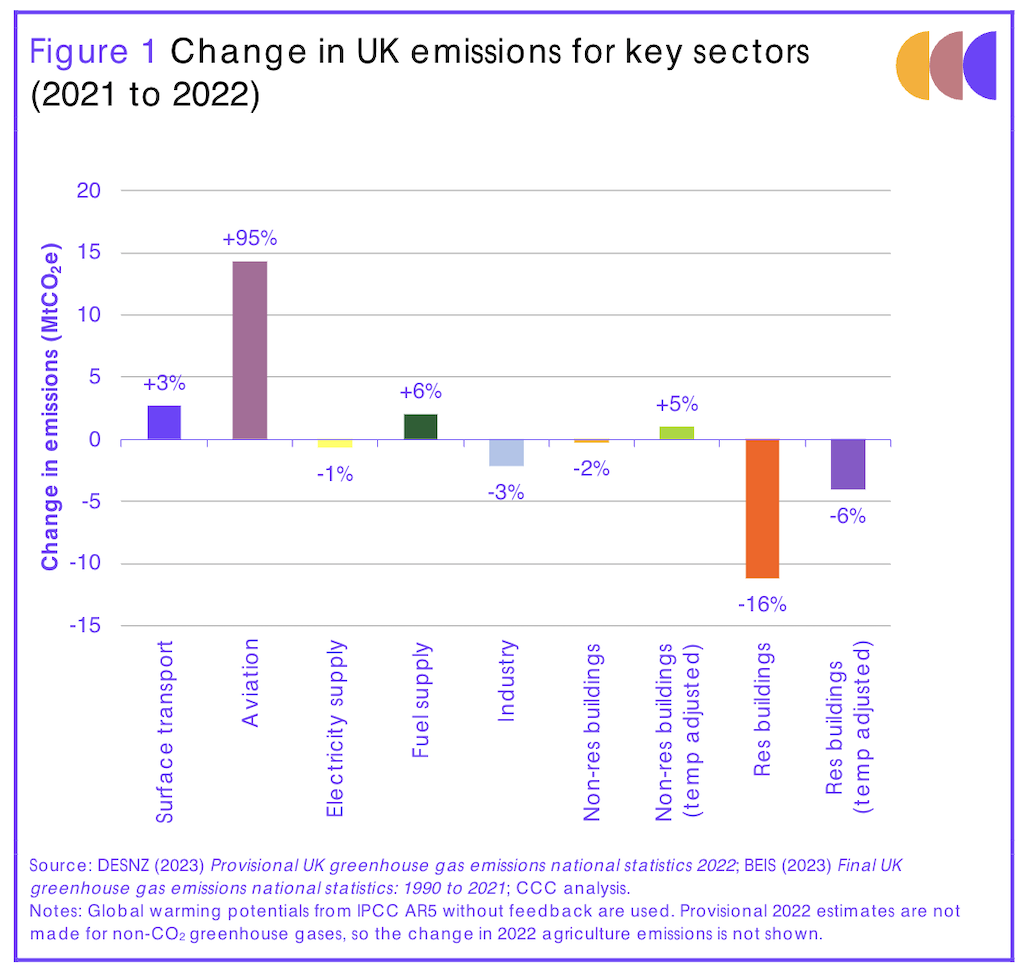

The report concludes that UK greenhouse gas emissions, including international aviation and shipping, were 46% below 1990 levels in 2022. This is a roughly 1% increase from the previous year, but 9% lower than pre-pandemic levels.

The dark red line in the chart below shows that the government’s new “delivery pathway” – the route it says it intends to take to reach net-zero – is actually less ambitious than the one it set out in 2021, shown by the lighter red line.

This is largely because the government expects its policies to be less effective at cutting emissions from road transport, the CCC says.

Overall, the UK would fall short of its 2030 nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement and its legally-binding sixth carbon budget, the CCC says.

This shortfall has been acknowledged by the government, which expects future “unquantified” emissions cuts to make up the gap.

However, the CCC emphasises that when existing policies are assessed for their credibility, a much larger shortfall emerges. Overall, it says the government is “missing coherent plans” and remains “over-reliant” on “specific technological solutions”.

It notes that the UK is now more likely to achieve its fourth carbon budget between 2023 and 2027 than it was last year, largely due to an increase in electric-vehicle sales and less road traffic following the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the CCC says its confidence in the government achieving its sixth carbon budget and NDC target has dropped “markedly” since 2022.

This is attributed to a combination of greater transparency, which allowed the committee to make a more detailed long-term assessment of the government’s plans and policies, as well as “delays in action leading to increased delivery risk”.

Government plans deemed “credible” by the CCC will now achieve emissions cuts just 49% below 1990 levels by 2035, compared to 55% in last year’s assessment.

These policies cover roughly one-fifth of the emissions cuts required to hit the sixth carbon budget, down from two-fifths last year.

As the chart above shows, UK emissions would essentially flatline for the next decade, if only “credible” policies are implemented and achieved.

With seven years to go until the NDC target, the report notes that “credible” plans cover just 25% of the emissions reductions needed to achieve it.

(The committee also assesses the proportion of emissions that have “some risks” or “significant risks” attached to them, as well as those that have “insufficient plans”. Overall, more emissions have missing or inadequate plans than in the 2022 assessment.)

The CCC repeats its “monitoring framework” from last year, noting that while there have been “some positive developments” action has been “significantly off track”.

In keeping with the greater transparency since the government’s carbon budget delivery plan, the committee notes that there are more targets in place than last year.

However, of the 50 key indicators identified in the report, there are now 25 identified as “significantly” or “slightly” off track, compared to 14 in the previous assessment. In contrast, it says progress against only nine of the 50 indicators is currently “on track”.

These indicators can be seen in the grid below.

Expansion of renewable power and the phaseout of coal have contributed to the majority of emissions cuts over the past few decades. This is alluded to in a government statement released in response to the CCC’s criticism, with a spokesperson stating:

“The UK is cutting emissions faster than any other G7 country and attracted billions of investment into renewables, which now account for 40% of our electricity.”

However, as the CCC stresses once again, the UK will need to decarbonise more than its power sector in order to achieve its emissions targets.

As the grid above shows, there are significant gaps in the transport, buildings, industry and agriculture sectors that need to be filled, according to the committee.

The report concludes that outside of the electricity supply sector, emissions cuts must almost quadruple from annual reductions of 1.2% between 2014 and 2022 up to 4.7% on average, between 2022 and 2030.

Even in the power sector, progress has begun to slow down. The CCC says there are “some risks” attached to a much larger proportion of renewables goals than last year, “predominantly due to the continued absence of a delivery strategy for the sector and increased delivery risks around planning, consenting and access to network connections”.

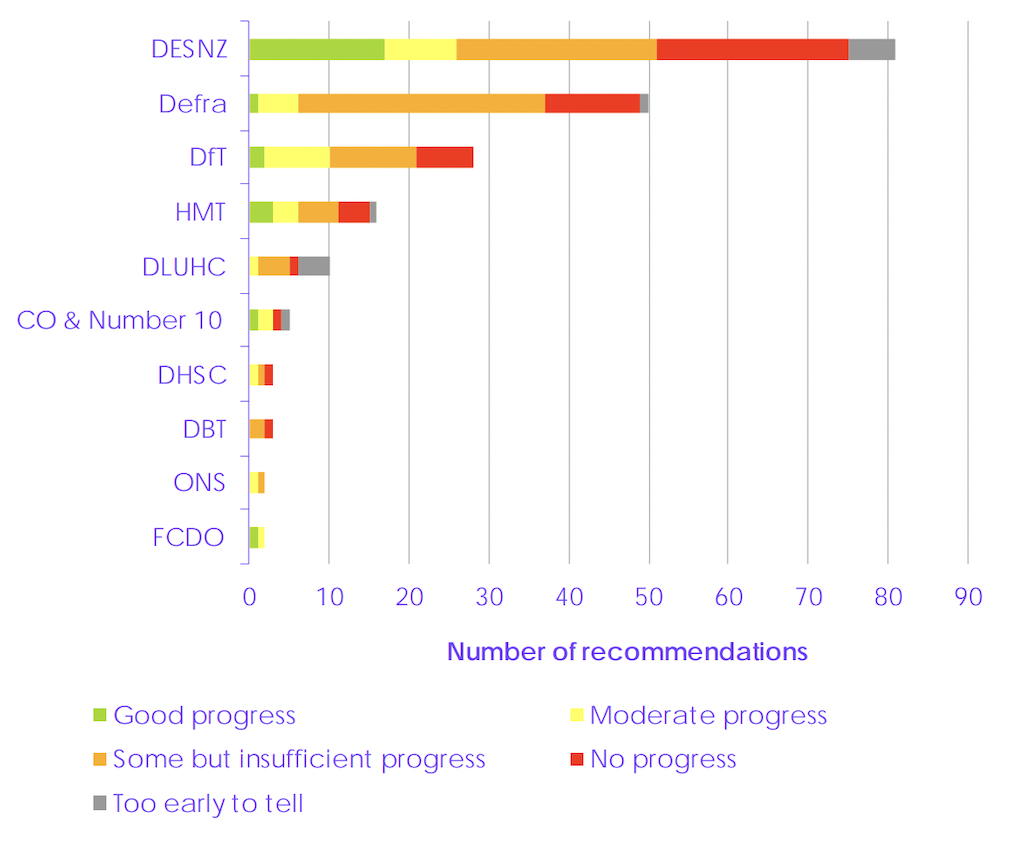

The CCC also assesses the progress made by individual government departments.

As the most significant department for the net-zero transition, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) has the largest number of missed recommendations from the list issued by the CCC last year.

However, the report singles out the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), which have “failed to achieve any priority recommendations and have made insufficient or no progress on a large majority of the non-priority recommendations”.

This lack of departmental progress can be seen in the chart below.

Overall, the CCC points to a “lack of urgency” in the four years since the government committed to its net-zero goal and concludes:

“The slow progress to date on delivery towards net-zero means that it is no longer tenable for the government to develop strategies that do not contain committed policies.”

Road transport

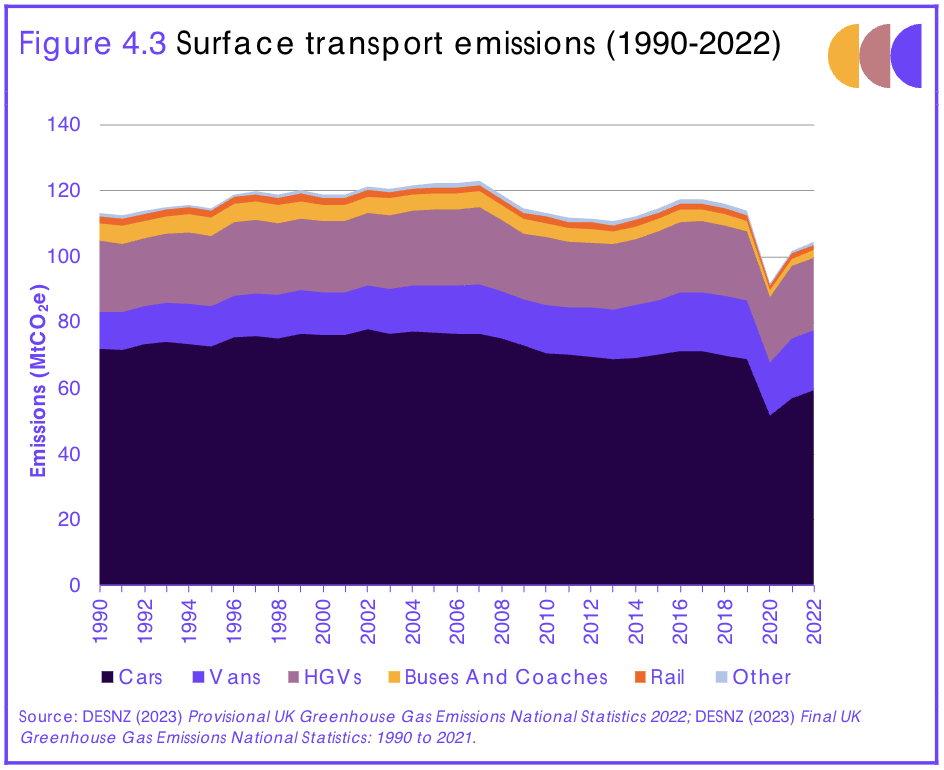

In 2022, surface transport emissions increased by 3% as travel continued to rebound following the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, according to the CCC. However, they remained 8% below 2019 levels, as a new “steady state” emerged.

Overall, surface transport contributed 23% (105 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e)) of the UK’s total emissions in 2022, making it the country’s highest-emitting sector.

The government’s CBDP aims for a reduction in surface transport emissions of 58% (61MtCO2e) by 2035 on 2022 levels, which the CCC says is a lower level of ambition than in the previous net-zero strategy.

The committee says this is due to two key changes: the acknowledgement that carbon savings from plug-in hybrid (PHEV) cars are around three to five times lower in the real world than previously assumed; and that policies aimed at supporting the public to choose lower-carbon modes of transport have been removed from the latest strategy.

The reduction in quantified ambition results in an abatement shortfall, which will need to be made up in order for the UK to meet its legislated carbon budgets, the CCC notes.

Moreover, policy progress has been delayed over the past year, the report says, increasing delivery risk across the surface transport sector.

There are only credible policies in place to meet 38% of required emissions reduction by the Sixth Carbon Budget period, it says. The government must now “proceed with urgency” to get plans within this sector back on track, the CCC adds.

One bright spot is that sales of electric vehicles (EVs) have surged and the share of electric cars has continued to increase ahead of the CCC’s central net-zero pathway.

In 2022, 17% of new car sales were EVs, four percentage points ahead of the CCC’s pathway. Availability in the second hand market has also grown, with the share of EVs within this growing from 0.7% in 2021 to 1% of sales in 2022.

Electric van uptake, however, has been less strong, with just 6% market share in 2022, the CCC says, although the industry’s outlook remains positive.

The CCC welcomes the results of the final consultation on the zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate, which will require manufacturers to sell a rising proportion of ZEVs.

While the mandate includes flexibilities that could slightly weaken its impact, the policy remains a credible delivery mechanism that the government must work at pace to ensure is implemented from 2024, says the report.

It also points to the potential to build on the progress made within the ZEV mandate, to drive forward the market for zero-emission heavy goods vehicles.

Although the share of EVs and the extent of supporting charging infrastructure has grown, provision of charge points remains inconsistent across the country and there are concerns about reliability and cost, the CCC says.

For example, the bottom 20% of local authorities average just 20 public charge points per 100,000 population, it says, as opposed to the national average of 55.

The charging network expanded by almost a third over 2022, but to keep pace with the uptake of EVs it must more than double in the coming year and beyond, the committee says. Its report states that sufficient progress in this area is “vital”:

“This is vital – if progress is insufficient, delayed or patchy, or if cost and reliability issues present barriers to use, it could undermine public confidence in the suitability of EVs and pose a serious risk to the achievement of the 2030 phase-out of new petrol and diesel vehicles.”

Beyond EVs, measures to limit growth in road transport will be crucial for decarbonising transport, the CCC notes. In 2022, the number of kilometres driven by road vehicles was 21% higher than in 2020, due to the lifting of travel restrictions following the pandemic. This was around 5% below pre-pandemic levels, as part of the emerging “steady state” caused by increases in home-working and the implementation of low-traffic neighbourhoods.

However, the government’s CBDP delivery pathway was largely lacking measures designed to reduce car demand. As such, compared to the CCC’s pathway, the report says car demand is on track to be a significant risk to meeting carbon budgets.

Additionally, there has been little progress in shifting to lower-carbon modes of travel. Public transport demand has been slower to recover following the pandemic than road traffic, with usage sitting at 80-90% of pre-pandemic levels.

The report says concerns around service provision and reliability increased in 2023 due to ongoing labour disputes, making public transport less appealing.

In addition, it notes that bus and rail prices increased by 80% and 43% respectively between 2010 and 2021, whereas the cost of running a car rose by just 27%.

(This disparity is partly due to continued freezes in fuel duty, which Carbon Brief analysis shows has raised UK CO2 emissions while costing the government at least £80bn.)

While cycling kilometres fell in 2021, they remained 16% higher than pre-pandemic levels, and a similar trend is apparent for walking, the report says.

Overall, an improved outlook for transport emissions has contributed to the improvement in the prospect of meeting the fourth carbon budget, the CCC says, but delays in developing the zero-emissions vehicle mandate could hamper this.

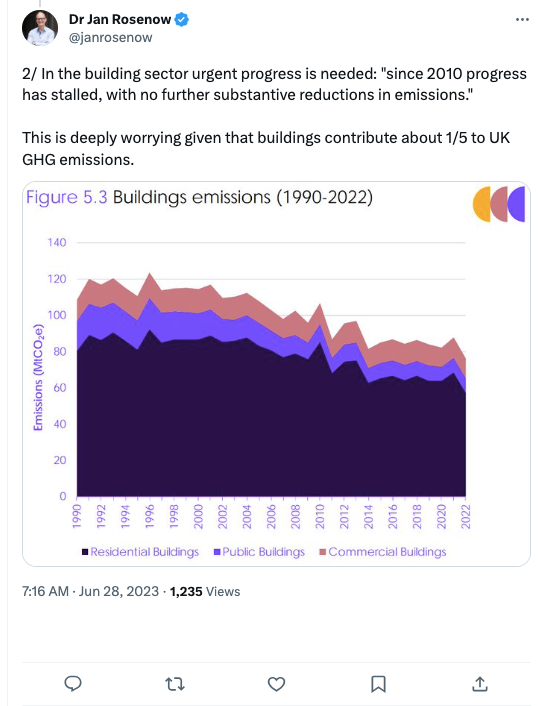

Buildings

Emissions from homes fell by 16% in 2022, according to the CCC, largely as a result of a milder winter – though high fossil fuel prices also played a role.

After adjusting for the temperatures over winter, emissions from homes fell 6%, the report notes. It says it is unclear how much of this reduction was due to improvements in efficiency, and how much due to people using their heating less as energy was unaffordable.

However, installation rates of energy efficiency measures continue to be below the necessary levels, according to the report, and actually fell further in 2022.

In addition, rates of heat pump installations are falling well below government targets, according to the CCC. The government is targeting 600,000 heat pump installations a year by 2028, but currently just one-ninth of this is being installed, and rates are not increasing fast enough.

The CCC highlights the urgent need for “significant” policies and programmes to underpin the delivery of low-carbon heat and energy efficiency.

The government is set to take a strategic decision by 2026 on the role of electrification and hydrogen in low-carbon heating systems. However, the CCC warns that the lack of a decision is creating systemic uncertainty, impacting the growth of the supply chains needed for low-carbon heating and limiting the rollout of infrastructure.

“Waiting three more years to set a clear direction will lead to further lost progress in buildings, and hinder infrastructure development more widely,” the CCC’s progress report notes.

The government should push ahead with no-regret and low-regret options, the CCC states, developing and moving forwards with a strategic approach. This should include pursuing electrification wherever feasible, with – at most – a small role for hydrogen in buildings.

Heat pumps are expected to be up to three times cheaper than heating homes with “green hydrogen” in the UK, according to research covered earlier this year by Carbon Brief.

Additionally, a “rapid and forceful” pursuit of zero-carbon new-build homes, energy efficiency improvements in existing buildings, and low-carbon heat networks should be undertaken by the government.

Beyond residential buildings, the CCC also highlights the need for a stable, long-term funding approach for offices and commercial premises.

“There are no convincing plans to decarbonise commercial buildings,” the progress report notes, with more needed to drive improvements across the sector.

Industry

Industry sits as the UK’s third highest-emitting sector, responsible for 14% of emissions in 2022 (63MtCO2e). The CBDP set out a target to reduce industrial emissions by 69% by 2035 on 2022 levels.

While emissions from industry fell by 3% in 2022, the pace of industrial decarbonisation needs to speed up in the next decade to around 8% per year out to 2030 if the UK is to hit this target, according to the progress report.

The CCC highlights the needs for the UK to improve its competitiveness when it comes to decarbonising industry, including mitigating the risk of carbon leakage – where production is relocated to countries with fewer emissions restrictions.

The government is consulting on a number of policies that could support this, including a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

As with cautions over the development of energy technologies, the CCC warns that companies investing in industrial decarbonisation may overlook the UK in favour of countries with more favourable policy support, such as the US’ Inflation Reduction Act or the EU’s proposed Green Deal Industrial Plan.

Overall, UK policy to decarbonise industry is not sufficient, the CCC finds. This includes a lack of a clear plan to support industrial electrification and little evidence of preparing to electrify at scale.

The report notes that the government has high ambitions for decarbonised steel production in particular, but significant barriers including the price of electricity, cost and difficulty of upgrading network connections and the uncertainty around the most appropriate fuel-switching technologies, remain for this and other industries.

Gaps in policy can also be found around resource efficiency, off-road mobile machinery and small and dispersed sites.

The decarbonisation of industry is particularly reliant on private sector commitment, but while the CCC says it is encouraging that companies are increasingly setting public emissions reductions targets, these are falling far short of what is required.

Finally, data availability in the sector remains a challenge, limiting monitoring, evaluation and policy implementation. The CCC reiterates its call from last year that the government should review, invest in and reform industrial decarbonisation data collection and reporting.

Fossil fuels and hydrogen

Fuel supply was responsible for 7% of UK emissions in 2022 (33MtCO2e), coming predominantly from fossil fuel supply, with small contributions from hydrogen production and bioenergy supply, according to the CCC progress report.

As mentioned in the introduction, the committee states within the progress report that the “expansion of fossil fuel production is not in line with net zero.” As part of this, the CCC recommends that the planning frameworks and guidance support a “clear presumption against new consents for coal production” and that the UK should set out a “clear position on exiting oil and gas”.

The North Sea Transition Deal committed to reducing emissions in the oil and gas industry to 50% below 2018 levels by 2030, a target that was reaffirmed in the CBDP, but was less ambitious that the 68% reduction the CCC estimated could be achieved.

Despite the government’s less ambitious target however, the CCC has downgraded its assessment of policy progress with regards to fuel supply over the last year.

This is in part a response to the government’s approval of a new coal mine, the continued delay to its biomass strategy – previously scheduled for 2022 and now expected later in 2023 – and new risks identified around the government’s hydrogen ambition.

In addition to the concern raised by the approval of the UK’s first new deep coal mine for 30 years in Cumbria, the new licensing round for oil and gas production the government committed to in the Energy Security Strategy is highlighted by the CCC.

It points to a letter sent to the then secretary of state for the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in February 2022 by the committee that explained increases in domestic oil and gas extraction would have a marginal effect on prices at most. It adds:

“The best way to reduce the UK’s exposure to volatile markets is instead to cut fossil fuel consumption through measures such as rapidly shifting to renewables, improving energy efficiency and electrifying end uses (such as heating, industry and transport).”

The government has set a target of up to 10 gigawatts (GW) of low-carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030, with at least half of this to come from electrolytic hydrogen. This risks being on the lower end of what is required however, notes the CCC, and there remains a lack of clarity on its hydrogen production ambition.

Setting a strategic decision for the end-uses of hydrogen will be key for the sector, it says, given the long infrastructure lead times. The CCC suggests the government should fast-track hydrogen transport and storage business models in order to keep “options open on the scale of hydrogen usage” whilst identifying a series of low-regret investment options.

Electricity

Emissions from the electricity sector in the UK fell by just 1% in 2022, compared with a year earlier, despite increases in renewable electricity capacity, the CCC says.

It attributes this to the UK being a net exporter of electricity in 2022, for the first time in 44 years. Electricity generated for export to continental Europe, where the French nuclear fleet was suffering major outages, meant higher than expected emissions in the UK, it explains.

While the precise impact of the additional gas power plants running for export purposes is hard to quantify, notes the CCC, it estimates that electricity supply emissions might otherwise have been around 6% lower in 2022.

The limited reduction in electricity emissions is shown in the figure below.

Power prices reached unprecedented levels in 2022, leading the government to step in with a number of support mechanisms for households and businesses.

One such measure was the government taking on the costs of climate and social policy – including support for low-carbon electricity and insulation for fuel-poor homes – which had previously been paid for via electricity bills.

By paying for these costs – often referred to as “green levies” – the government effectively cut the ratio of electricity prices to gas prices.

According to the CCC, it is now “essential that this improvement in relative prices is made permanent,” helping to rebalance electricity and gas prices, which the government has already committed to implement by March 2024.

(Media reports over the weekend indicate that, on the contrary, the government intends to reapply policy costs to consumer electricity bills from July, despite having pledged last autumn to pay for levies out of general taxation for two years.)

Mirroring many other concerns from the CCC, action to decarbonise the electricity sector is not moving fast enough according to the progress report, with deployment rates falling short of what is required by the government’s stretch targets, in particular for solar.

Despites an increase in renewable electricity capacity in 2022, the UK government missed an opportunity for rapid deployment of onshore wind and solar, which could have both increased clean energy supply and helped to reduce the country’s dependence on imported fossil gas, the CCC notes.

To enable this, however, planning policy needs “radical reform to support net-zero,” says the CCC. There is currently a risk of the net-zero transition being “stymied or delayed by restrictive planning rules”, it adds.

This is already becoming evident with regards to the capacity of electricity networks in the UK, with renewable developers facing waits of 10-15 years for a grid connection.

Agriculture and land use

The CCC’s progress report says that in 2021 agriculture and land use were responsible for 11% of the UK’s emission (49MtCO2e), an increase of 1MtCO2e on 2020 levels.

Agriculture and land use is an area with some of the biggest divergence between the 2023 CBDP, which set out plans to reduce emissions by 29% on 2021 levels by 2035, and previous targets. Emissions savings under the CBDP by 2035 is now 32% less than the level set out in the 2021 Net Zero Strategy, largely due to a reduction in land use sector ambition.

The impact of methodology changes in how emissions are estimated within the CBDP are unclear, the CCC notes, with projected emissions in the pathway for both agriculture and land use estimated to be 1% lower in the CBDP than in the 2021 strategy.

The CCC also highlights concern around the dependence on speculative technology and innovation within the CBDP. Around a third of abatement within agriculture and land use is expected to come from these elements, it notes, but there are currently no supporting policies in place.

There is a limited focus on demand-side measures to reduce emissions within agriculture and land use in the UK, with measures such as encouraging healthier, more sustainable diets overlooked. Failing to address this gap could result in a “missed opportunity” the CCC warns, which could mean emissions reductions are insufficient to meet CBDP targets.

Other concerns raised by the committee include land-use change measures falling “well short of what is required” including those for the delivery of woodland and peatlands, the significant gaps in agri-environment policies and the reliance on voluntary measures which is “stalling progress”.

As for industry, there is a risk of carbon leakage from trade in agricultural products as the UK decarbonises the sector, as well as risks from livestock numbers failing to fall in line with demand as UK diets change, resulting in exports without the benefits of domestic methane reduction and release of land.

Having delayed its planned land use framework, the UK government must now produce a comprehensive UK land use strategy, the CCC says. This will be “vital” to overcome current barriers and to ensure action is aligned across the devolved administrations.

CO2 removal

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) still represents 0MtCO2 in the UK, the CCC says, with no projects currently operating in the country despite the expectation that they will scale rapidly from the late 2020s.

This is an area where the government has made progress, the CCC notes, including announcements that eight projects are set to be developed within its first two CCS “clusters” and that the process for choosing the next two clusters has begun.

But there remains gaps in CCS policy, says the CCC, the broader programme for the technology is still behind schedule, and there is a lack of detail on the timelines for selection and support for the second two clusters.

Details are still missing for how the pledged £20bn into CCUS will be spent and there is still no detailed plan or policy framework for CO2 transport, the CCC adds.

Engineered emissions removal projects will have a high upfront capital and operating cost, due to the risks associated with novel technologies, and therefore require government support within the early stages, according to the committee.

There needs to be greater clarity on this from the government, the CCC says, with a response to the engineered removals business models consultation needed this year.

Beyond these elements, stringent monitoring, reporting and verification as well as high quality standards for biomass used for bioenergy with CCS (BECCS) will be crucial, it adds, improved coordination across devolved administrations is needed, public engagement must be undertaken and the government must consider alternative arrangements to account for potential delays or complications in project delivery for these nascent technologies.

Aviation and shipping

The CCC’s progress report reiterates its sixth carbon budget advice that there should be no net expansion of UK airports. Since issuing this advice, the CCC notes that airports across the country have increased their capacities and continue to develop proposals for further expansion. The progress report states:

“This is incompatible with the UK’s net-zero target unless aviation’s carbon-intensity is outperforming the government’s pathway and can accommodate this additional demand. No airport expansions should proceed until a UK-wide capacity management framework is in place to annually assess and, if required, control sector CO2 emissions and non-CO2 effects.”

Aviation accounted for 7% of the UK’s emission in 2022 (29MtCO2e). This was up 95% from 2021, due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic restricting travel, but still 25% below 2019 levels.

The government’s “jet zero” strategy, published in July 2022, committed to a 70% increase in passenger demand by 2050, while relying heavily on technology to compensate for the increased emissions this represents.

This is a high risk approach, in particular the assumed rapid uptake of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) assumed within the strategy, the CCC says. The government does not have a policy framework in place to ensure emissions reductions occur if these technologies are not developed and delivered in time and at a sufficient scale, it adds.

Demand management would be the most effective way of reducing aviation emissions, according to the progress report. The government should therefore take advantage of this by developing a suite of policy and technology options to address demand, it adds.

Beyond this, the government should establish a framework to manage airport expansion across all devolved nations over the next year and bring it into force by 2024 at the latest, advises the CCC.

A contingency plan should also be developed to manage the possibility that SAFs fall behind expectation – the Jet Zero Strategy set out an SAF mandate target of 10% by 2030, but the CCC’s main pathway assumes just 2% SAF uptake by 2030.

Shipping accounted for 3% of the UK’s emissions in 2022 (12MtCO2e), a small increase on 2021 by still 12% below 2019 levels.

Little has changed with regards shipping policy over the last year, the CCC notes, calling on the government to publish its response to the “course to zero” consultation and embed this within its updated “clean maritime plan” in 2023.

Waste and F-gases

Efforts to reduce emissions within the waste sector, which accounted for 6% of the UK’s emissions in 2021 (25MtCO2e), are being undermined by the continued growth of energy from waste (EfW), says the CCC.

Emissions from EfW are already higher than the government’s CBDP target, with a comprehensive systems approach needed to reduce these urgently needed, the CCC says, including a moratorium on additional EfW capacity.

Improvements to recycling will be key to reducing EfW and landfill, with the committee urging that the implementation of planned reforms to both recycling and packaging not be delayed.

Beyond this, progress should be made on tackling emissions from wastewater, rolling out CCS at EfW facilities and more generally developing greater strategic coordination of plans to decarbonise the waste sector, the CCC says.

Fluorinated gases (F-gases) meanwhile represented 2% of the UK’s emissions 2021 (11MtCO2e). While emissions from this sector have fallen in recent years, they remain higher than in the early 2000s, and there is a risk they could increase with the rollout of heat pumps, as most use F-gas refrigerants, it says.

It is expected that 90% of the reduction in emissions from F-gases by 2035 will come via the existing UK F-gas regulation, which the government has committed to reviewing.

There is no clear legislative timeframe of the extension of this regulation, an element the government must provide additional clarity on, says the CCC.