Factcheck: Can new UK oil and gas licences ever be ‘climate compatible’?

Daisy Dunne

02.24.22Daisy Dunne

24.02.2022 | 12:01amThe UK made history in November 2021 by helping to secure the first mention of the need to tackle fossil fuels in a global climate agreement, at the COP26 summit in Glasgow.

But just months later, the UK government is reportedly considering “fast-tracking” new North Sea oil and gas licences, amid pressure from a vocal minority of Conservative politicians and commentators who claim new fossil fuel production is the solution to the energy crisis.

Unlike other countries, such as Denmark, Ireland and France, the UK has not ruled out issuing new licences for offshore oil and gas exploration.

Instead, it has proposed that new licensing rounds could take place if the oil and gas sector can pass a “climate compatibility checkpoint” that ensures any new production is in line with the country’s goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

Ministers argue that, given demand for oil and gas is expected to continue on the journey to net-zero – albeit at a much lower level – it would be more climate-friendly to meet this with “cleaner” domestic production rather than imports.

But many have criticised the idea, citing an influential report from the International Energy Agency finding there is no space for any new fossil fuel production, if the world is to meet its aspiration of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

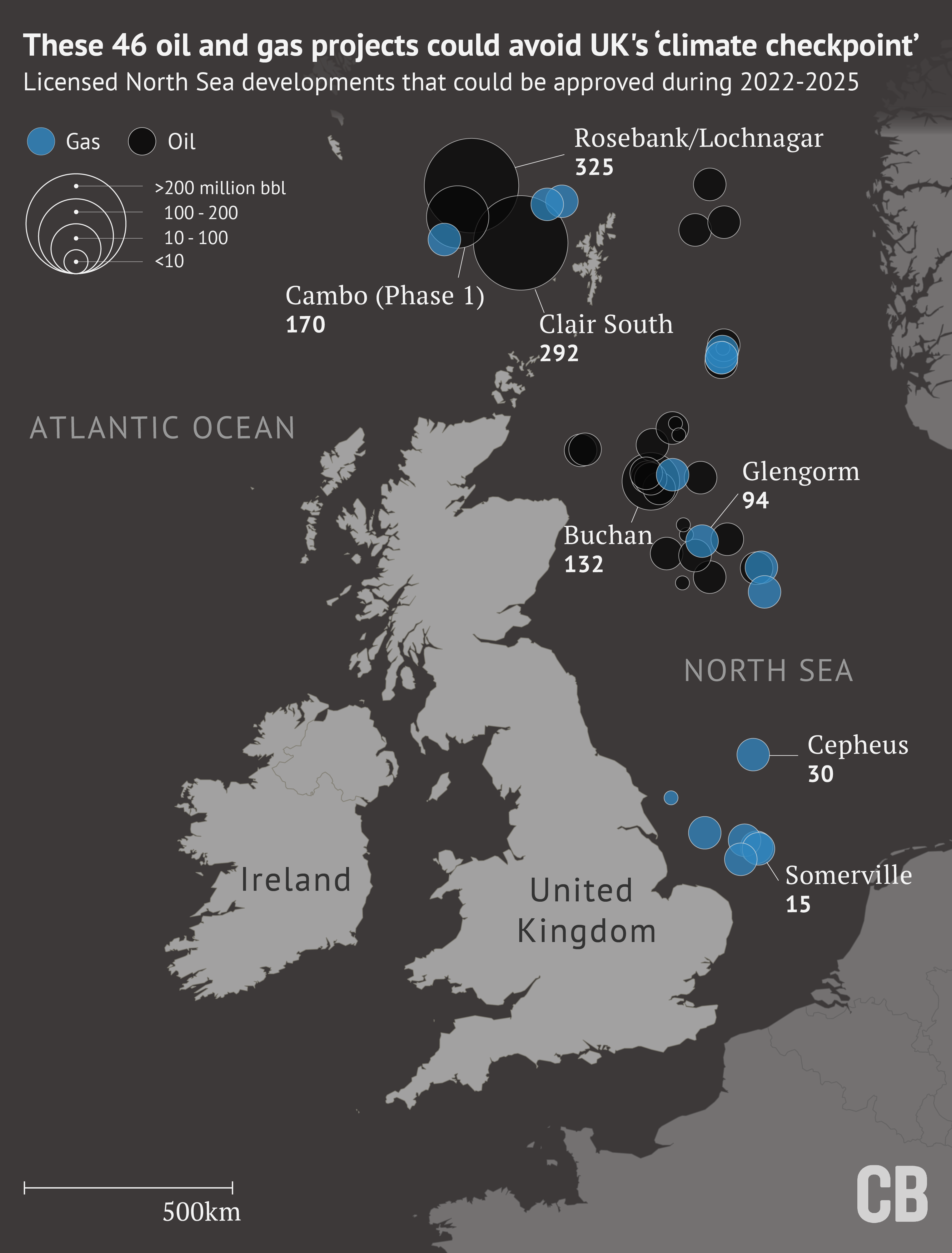

Critics also point out that many oil and gas projects have already obtained a licence and will not be subject to the checkpoint under its current design. Between 2022 and 2025, up to 46 such oil and gas projects could be approved, together producing 2.1bn barrels of oil equivalent, new analysis finds. (Carbon Brief has mapped these projects below.)

Below – and in light of new evidence published today by the UK’s Climate Change Committee (CCC) – Carbon Brief examines the details of the UK’s climate compatibility checkpoint, how demand for oil and gas is likely to change in the future and whether new licences can ever be “climate compatible”.

UPDATE 7 OCTOBER: The UK’s new government under Liz Truss has opened a fresh licensing round for oil and gas in the North Sea, which could see up to 100 licences being awarded.

It comes after the final design for the “climate compatibility checkpoint” was announced by the new government in September. The final version only considers the climate impact of drilling operations in the North Sea and does not cover emissions from the burning of oil and gas, as proposed during the consultation (see below).

What is the UK’s proposed ‘climate compatibility checkpoint’ for oil and gas licences?

The UK government first announced its intention to launch a new “climate compatibility checkpoint” for oil and gas licences in a press release issued in March 2021.

This press release was centred around the government’s North Sea transition deal – a plan to slash oil and gas production emissions and facilitate the move towards renewables.

The deal aims to cut operational emissions from oil and gas in the North Sea by 25% on 2018 levels by 2027 and by 50% by 2030. (The government’s climate adviser, the CCC, recommended a firmer 68% reduction in operational emissions by 2030 under its central pathway for reaching net-zero by 2050.)

Stating that “an orderly transition [away from fossil fuels] is crucial to maintaining our energy security of supply”, the press release says:

“The UK government will therefore introduce a new climate compatibility checkpoint before each future oil and gas licensing round to ensure licences awarded are aligned with wider climate objectives, including net-zero emissions by 2050, and the UK’s diverse energy supply.”

The press release adds that the checkpoint will be “dynamic”, assessing “ongoing domestic need for oil and gas while expecting concrete action from the sector on decarbonisation”. It continues:

“If the evidence suggests that a future licensing round would undermine the UK’s climate goals or delivery of net-zero, it will not go ahead.”

(The 51-page document for the North Sea transition deal does not make any mention of the checkpoint and Carbon Brief understands a reference to it was added to the press release after the deal was finalised. The UK government had not responded to this claim by the time of publication.)

Further details emerged in December, when the government officially launched its consultation into the design of its proposed climate checkpoint.

The consultation document explains that, before an oil and gas company can explore, drill or begin production on the UK Continental Shelf, they must first be granted a licence from the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA).

(The OGA is a government company – with business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng as the sole shareholder – which juggles two seemingly conflicting central objectives: maximising the economic recovery of UK oil and gas and assisting the government in meeting its net-zero target.)

A licence grants the operator exclusive rights to explore a certain area. However, it does not give the holder consent to develop infrastructure or begin oil and gas extraction. For this, more official permissions must be obtained.

Licences are usually handed out after “licensing rounds”, which allow operators to bid for specific areas. As it is currently proposed, the checkpoint would come in ahead of a new licensing round, the consultation says.

The checkpoint will consist of a series of tests that the oil and gas sector must pass in order for a new licensing round to take place, the consultation adds. If the oil and gas sector fails the tests outlined in the checkpoint, new licensing rounds will not take place.

It lists six potential tests that may be included in the checkpoint:

- Potential test 1: Is the oil and gas sector reducing its operational (scope 1 and 2) emissions in line with the government’s climate commitments?

The consultation document says this test would examine how the sector’s historical performance and future plans for reducing operational emissions compare to commitments in the North Sea transition deal.

However, it also acknowledges that the North Sea transition deal is not in line with the CCC’s recommendations for reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 nor the UK’s international pledge to cut its emissions by 68% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. It says that if “in the future, stronger targets are agreed for the North Sea transition deal, these would then be used for this test”.

- Potential test 2: Is the oil and gas sector making “strong progress” on reducing its operational emissions when compared to other oil and gas producing countries?

This test would “benchmark the UK oil and gas sector against other global producers in terms of associated production emissions”, the document says. “This criterion would be satisfied as long as the UK remained at a certain ranking with respect to this benchmark,” it adds.

- Potential test 3: Is the UK expected to remain a net importer of oil and gas?

The consultation says this test would be met as long as the UK remains a net importer of oil and gas “in order to minimise reliance on imports”.

The UK is currently a net importer of both oil and gas. Almost all UK gas is consumed in the country, with a small proportion piped to Ireland and the Netherlands. By contrast, more than 80% of UK oil is exported on the global market.

The consultation says that “while this might lead some to conclude that continued gas production would be preferred over oil production”, it is worth noting that oil and gas are usually found together in the North Sea. “For that reason, we have rejected the idea that oil and gas could be licensed separately,” the consultation says.

- Potential test 4: Is the oil and gas sector developing “energy transition technologies” at the rate set out by the North Sea transition deal?

This test is designed to “incentivise investment in, and development of, the technologies we will need for the energy transition”, the consultation says. This includes carbon capture and storage and hydrogen.

The oil and gas sector would fail this test if it were “to fall behind relative to a predefined trajectory towards the targets in the North Sea transition deal”, the consultation adds.

- Potential test 5: Is there consideration of international scope 3 emissions?

Scope 3 includes all the emissions in an organisation’s value chain. Crucially, it includes emissions from the burning of extracted oil and gas, wherever that takes place. For this reason, scope 3 emissions are much higher than those from scope 1 and 2.

The consultation says “this test has been proposed in conversations with stakeholders” but “as of yet, a full proposal for how the test would work has not been presented”.

- Potential test 6: Is there consideration of the “global production gap”?

This test refers to the gap between the “global sum of governments’ projections for oil and gas production” and “what the world can afford to burn” if it is to limit global warming to 1.5C, which is the aspiration of the Paris Agreement. (A recent UN review found governments’ production plans and projections would lead to about 57% more oil and 71% more gas in 2030 than would be consistent with keeping warming to 1.5C.)

The consultation says “a test which considers the production gap has been proposed in conversations with stakeholders”, but adds that “opinions differ on what production levels consistent with 1.5C would look like for a single nation”.

The consultation period for the checkpoint is open until the end of February. After this, the government says it will “consider the responses received” and “announce the outcome of the final checkpoint design in due course”.

How could the checkpoint affect future North Sea oil and gas production?

The UK is the second-largest producer of oil and third-largest producer of gas in Europe, but its production from the North Sea is in decline. Oil production peaked in 1999, when the sector produced approximately six million barrels per day. Meanwhile, gas production peaked in the UK continental shelf in 2000.

Despite the decline, the UK’s oil and gas reserves “remain at a significant level”, according to the OGA. It estimates that, as of the end of 2020, UK oil and gas reserves stood at 4.4bn barrels of oil equivalent – enough to sustain production until 2030.

As it currently stands, the climate compatibility checkpoint would be implemented before a new licensing round.

This means that a large number of new oil and gas projects – which already hold a licence, but have not yet received development consent or a final investment decision – could go ahead without being subject to the climate compatibility checkpoint.

Between 2022 and 2025, up to 46 such oil and gas projects could be approved, according to analysis by the campaign group Uplift using data from consultancy Rystad Energy.

These projects, including the Cambo oil field along with lesser-known but bigger developments, such as Rosebank and Clair South, together have the potential to produce up to 2.1bn barrels of oil equivalent over their lifetimes.

When burnt, this amount of fuel would produce around 900m tonnes of CO2 – more than twice the amount produced by the UK economy each year.

The 46 projects are visualised on the map below. The 10 biggest oil and gas projects that could be approved are listed in tables below.

These 46 oil and gas projects could avoid UK’s ‘climate checkpoint’

Licensed North Sea developments that could be approved during 2022-2025

Rosebank/Lochnagar

325

Gas

Oil

>200 million barrels of oil equivalent

100 – 200

10 – 100

<10

Cambo (Phase 1)

170

Clair South

292

ATLANTIC OCEAN

Glengorm

94

Buchan

132

NORTH SEA

Cepheus

30

United

Kingdom

Ireland

Somerville

15

500km

| Oil project | Resources (Million bbl) |

|---|---|

| Rosebank/Lochnagar | 325 |

| Clair South | 292 |

| Cambo Phase 1 | 170 |

| Buchan | 132 |

| Galapagos (Hutton NW redevelop) | 81 |

| Pilot | 79 |

| Perth | 55 |

| Cheviot (Emerald redevelop) | 50 |

| Serenity | 45 |

| Marigold | 44 |

| Gas project | Resources (Million bbl) |

|---|---|

| Glengorm | 94 |

| Tornado | 60 |

| Harding (redevelop/gas blowdown) | 58 |

| Jackdaw | 56 |

| Leverett | 40 |

| Gryphon (redevelop/gas blowdown) | 35 |

| Cepheus | 30 |

| Victory | 29 |

| Tullich (redevelop/gas blowdown) | 25 |

| Goddard | 22 |

The failure to include future projects with existing licences should be considered a “huge weakness” of the checkpoint’s current design, says Tessa Khan, an environmental lawyer and director of Uplift. She tells Carbon Brief:

“There are many new oil and gas fields under existing licences which are due for approval in the next couple of years. These would increase production by billions of barrels of oil.

“There’s a big question mark over how much oil and gas there is in unlicensed areas in the North Sea. So excluding what we know to be billions of barrels of oil under existing licences in fields that haven’t been approved is a massive loophole in this test.”

Nicola Sturgeon, the first minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party, in August 2021 wrote to prime minister Boris Johnson urging him to amend the checkpoint to cover new projects that have already been issued licences. She told Johnson:

“I am asking that the UK government agrees to reassess licences already issued but where field development has not yet commenced. That would include the proposed Cambo development.

“Such licences – some of them issued many years ago – should be reassessed in light of the severity of the climate emergency we now face, and against a robust compatibility checkpoint that is fully aligned with our climate change targets and obligations.”

In a letter to the business secretary published on Thursday, the CCC also advises that the climate compatibility checkpoint should be applied at later stages of development. The letter reads:

“We encourage you to set stringent tests to the licensing of exploration. Equivalent tests should also apply to later development stages, such as consenting of production.”

CCC chair, Lord Deben, told a press briefing held on Wednesday that applying climate tests at later stages of development would be a “sensible thing” to do. He said:

“It seems a little odd that if you have a programme which might take 40 years, that you make a decision at one point and you don’t make any similar decision at any later time, even though the circumstances around it would be very, very different.”

CCC chief executive Chris Stark added:

“The climate doesn’t care: It doesn’t make any difference between a licensed project or a consented project.”

How will demand for oil and gas in the UK change in the coming decades?

Proponents of continued North Sea exploration say it will be needed to meet the UK’s future oil and gas demand.

Though the UK has fast transitioned away from coal in the last few decades, it remains heavily reliant on oil and gas.

Oil and gas provided 73% of the UK’s primary energy supply in 2020, according to official data. Oil and gas currently play a particularly large role in providing fuel for transport and heat for buildings.

However, as the UK journeys towards net-zero over the coming decades, demand for fossil fuels is set to shift dramatically.

The CCC’s “sixth carbon budget” report provides a blueprint for how the UK can reach net-zero by 2050.

Its central pathway for reaching net-zero –known as the “balanced pathway” – sees far-reaching change across every sector of the economy in the coming years.

For example, this pathway requires a phaseout of new petrol cars and vans by 2032, new gas boilers by 2033 and unabated gas power production by 2030. (“Unabated” refers to production without carbon capture and storage). At the same time, renewable power, electric cars and heat pumps in homes are rapidly scaled up.

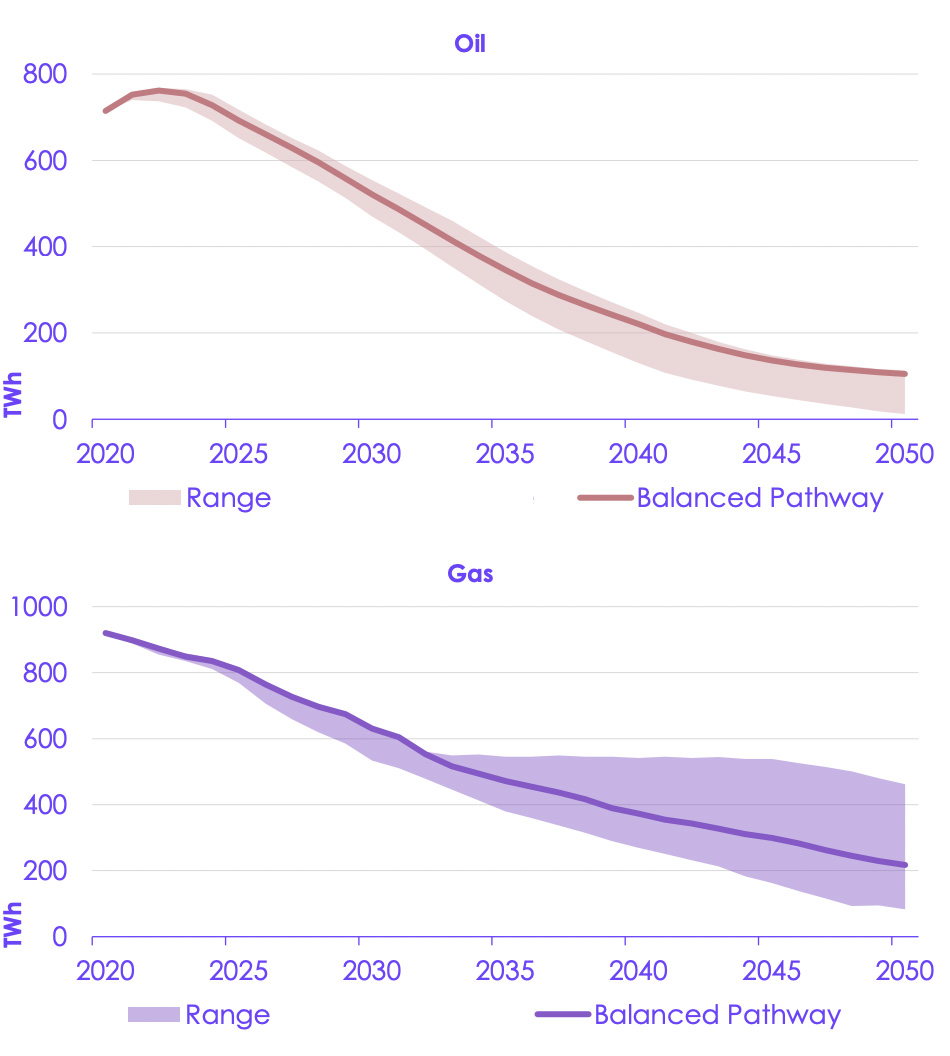

Under the balanced pathway, demand for oil falls by 85% on 2020 levels by 2050, whereas demand for gas falls by 76%.

The charts below, taken from the CCC’s letter published on Thursday, show how energy demand for oil (top) and gas (bottom) is expected to change from 2020 to 2050.

On the charts, the central line shows how demand changes under the CCC’s balanced pathway while shading indicates the range from other scenarios. (As well as coming up with a central balanced pathway for net-zero, the CCC has also created a range of other possible scenarios including various degrees of technological innovation and social change.)

By 2050 under the balanced pathway, “petroleum use is mainly restricted to the aviation sector, while gas use is limited to combustion with CCS for power generation and industrial processes and phased out of use in buildings”, according to the CCC’s sixth carbon budget.

Under the CCC’s most optimistic scenario called Tailwinds – which assumes extensive behavioural change and innovation – the drop in expected oil and gas demand is even steeper. Under this scenario, oil demand is expected to decline by 98% by 2050, while gas demand is expected to drop by 91%.

The CCC has also analysed how the UK’s position as a net importer of both oil and gas is expected to change on the journey to net-zero.

The charts below show how demand for oil (top) and gas (bottom) under the CCC’s balanced pathway (purple) compares to OGA projections for future oil and gas production (yellow). (The OGA projections include both current and new fields.)

(The bottom chart shows demand under a scenario with CCS (dashed line) and a scenario with no CCS (dotted line).)

This chart indicates that, under the balanced pathway to net-zero, the UK is expected to remain a net importer of both oil and gas for at least a few decades.

However, the UK’s net imports of oil and gas are expected to decline if consumption falls in line with the CCC’s balanced pathway.

Can new UK oil and gas licences ever be ‘climate compatible’?

Three-quarters of all global greenhouse gas emissions come from fossil fuel energy production.

And, at the global level, there is clear evidence to suggest that continued fossil fuel expansion is not compatible with efforts to keep global warming to 1.5C, the aspiration of the Paris Agreement.

An influential IEA report, commissioned by the UK government in 2021 ahead of COP26, said there is no space for further fossil fuel expansion globally if the world’s energy sector is to hit net-zero by 2050 as part of keeping warming below 1.5C.

In addition, a scientific paper published in Nature in 2021 estimated that 60% of oil and gas reserves must remain in the ground if the world is to have half a chance of meeting the 1.5C target.

Despite the warnings, fossil fuel production is still set to soar worldwide. A recent UN review found governments’ current production plans would lead to about 57% more oil and 71% more gas in 2030 than would be consistent with keeping warming to 1.5C.

Some researchers and campaigners say this evidence alone suggests that any new UK licences could not be climate compatible.

Navraj Singh Ghaleigh, a senior lecturer in climate law at the University of Edinburgh, tells Carbon Brief:

“The basic idea of the checkpoint – that any future licensing is properly aligned with the UK’s climate commitments – is a good one.

“The tension is we have a raft of scientists and reports which say that there is no new oil and gas production, and therefore licensing, that is compatible with 1.5C. So, in that sense, what the UK government is trying to do is not plausible.”

Given the global picture, the idea that new oil and gas licences could be climate compatible is “incredibly confused”, adds Khan:

“The whole premise that there is such a thing as a climate compatible oil and gas licence in the UK in 2022 is fundamentally misconceived.

“It underlines that the government is trying to square a circle here, which is the whole notion that new oil and gas licences are compatible with Paris Agreement climate commitments in 2022.”

But what about the argument that it would be more climate-friendly for the UK to meet continuing oil and gas demand in coming decades with domestic supply rather than imports?

This question is explored by the CCC in its letter to the government published on Thursday.

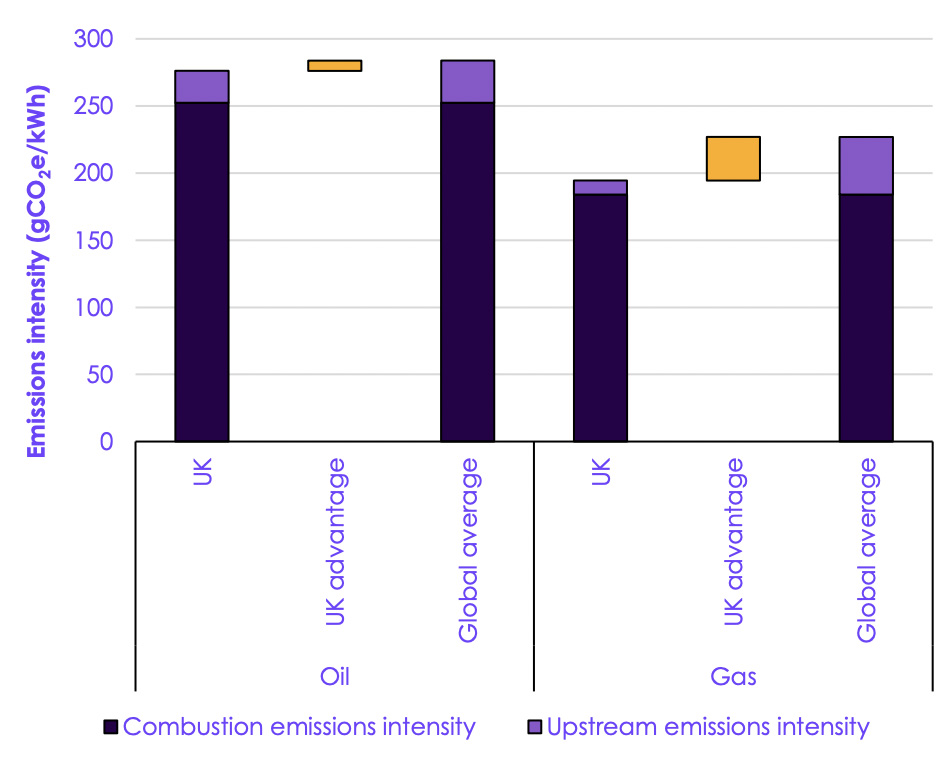

CCC analysis finds that the emissions intensity of oil and gas produced by the UK is lower than the global average, suggesting there could be some “advantage” to domestic production, it says.

The chart below shows how the emissions intensity from UK oil (left) and gas (right) production compares to the global average, with this potential advantage highlighted in orange.

It is worth noting, however, that the UK is not currently outperforming its biggest import partners when it comes to oil and gas production standards, says Khan:

“By far our biggest partner in terms of oil and gas imports is Norway – and they have significantly cleaner operational production than we do in terms of emissions intensity.”

And, at present, the emissions intensity of UK oil and gas production is on the rise. Analysis by Unearthed found that the emissions intensity of UK oil and gas production reached a record high in 2021, after declining slightly between 2018 and 2020.

In its letter to the government, the CCC says that while the emissions intensity of UK oil and gas production may be “relatively low”, any extra fossil fuel production will add to a larger global market, potentially undermining any emissions advantage in the UK with higher global oil or gas demand overall:

“UK extraction has a relatively low carbon footprint (more clearly for gas than for oil) and the UK will continue to be a net importer of fossil fuels for the foreseeable future, implying there may be emissions advantages to UK production replacing imports.

“However, the extra gas and oil extracted will support a larger global market overall…the evidence on new UK oil and gas production is therefore not clear-cut.”

The CCC adds that, due to a lack of available data, it has “not been able to establish the net impact on global emissions of new UK oil and gas extraction” – further hamstringing its ability to make decisive recommendations to the government.

(Stark tells Carbon Brief that this lack of data may force the government to “go back to the drawing board” on some of the proposed tests included in the consultation for the checkpoint.)

Because of the uncertainty, the CCC does not recommend an outright ban on new oil and gas licensing. Instead, the letter reads:

“We would support a tighter limit on production, with stringent tests and a presumption against exploration.”

The letter also notes that, according to official data, it takes an average of 28 years for an exploration licence to lead to oil and gas production. Because of this, any licence given now may not be contributing to supply until the 2040s or 2050s.

A major factor in the CCC’s decision to support an end to new exploration is that it would “send a clear signal” to the world that the UK is committed to the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C target, Stark told the press briefing:

“We think an end to UK exploration is now credible, but on the strength particularly of the signal it would send…a clear signal the UK is committed to 1.5C, just as we said at COP26.”

This clear signal could particularly boost efforts of UK COP26 president Alok Sharma, who is tasked with convincing other countries to produce more ambitious climate pledges in line with the 1.5C by the end of this year, added Lord Deben:

“It would give considerable support to the British government’s commitment to complete the work of COP26 during this coming year.”

At COP26, a small group of countries led by Costa Rica and Denmark launched a new alliance for ending new oil and gas extraction, known as the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance. The UK is not currently a member.

Ryan Wilson, a policy analyst at the research group Climate Analytics, says that the UK’s climate reputation could already be threatened by its reluctance to rule out more oil and gas licences – as well as by the lack of ambition contained within its North Sea transition deal. He tells Carbon Brief:

“In general, encouraging future exploration and extraction is a black mark, but also proceeding with an agreement that falls short of what their own statutory body has advised would be necessary is an even bigger black mark.”

Update: This article was amended after publication to amend Uplift analysis.