Q&A: Can debt-for-nature ‘swaps’ help tackle biodiversity loss and climate change?

Multiple Authors

07.16.24Multiple Authors

16.07.2024 | 3:23pmSo-called “debt-for-nature swaps” have regained prominence in recent years as part of efforts to raise finance for conservation efforts across biodiverse developing countries.

These “swaps” are financial agreements in which a conservation organisation or government reduces, restructures or buys a developing country’s debt at a discount in exchange for investment in local conservation activities.

Despite a biodiversity “finance gap” estimated at $700bn per year, little finance has been forthcoming from developed countries to help debt-distressed lower-income countries meet their biodiversity and climate targets.

One expert, who helped Ecuador negotiate a debt conversion deal in 2023, tells Carbon Brief that these swaps are “a very tangible strategy that is starting to be proven”.

He adds that they are one of the “big sustainable financing tools that can help” support global-south countries in following through on international treaties.

However, critics are less optimistic about the feasibility of debt-for-nature swaps.

Another expert tells Carbon Brief that the swaps are “far too small to have any impact at all” on the debt of developing countries and that they are “not even marginal to a solution at the current level of their size”.

Additionally, she says, “there’s no evidence that they have worked for nature”.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief examines how debt-for-nature swaps work, the criticism they have received and whether they can alleviate biodiversity loss and climate change in developing countries.

- Where did the idea of debt-for-nature swaps come from?

- How do debt-for-nature swaps work?

- How are they gaining traction in nature finance and conservation policy?

- What are some of the chief criticisms of debt-for-nature swaps?

- Can debt-for-nature swaps be done better?

Where did the idea of debt-for-nature swaps come from?

The idea of debt swaps emerged in response to the global debt crisis of 1982-83 brought on by multiple shocks to the world economy.

The 1979-80 “oil shock”, for example, more than doubled the real price of oil for the oil-importing developing countries, raising interest rates on debt and reducing how much foreign exchange they could raise to service their debts.

This mushrooming crisis led to the creation of a secondary market for developing country debt in 1982, where loans to developing countries could be traded at a market-determined price.

This paved the way for “swaps” of various kinds, where banks could trade their foreign debt at a discount and reduce their financial exposure to precarious loans, while private investors could gain a foothold in new markets that were otherwise closed off to them.

In 1984, ecologist Dr Thomas Lovejoy – then a vice president of science at WWF – wrote a column in the New York Times advocating for swaps where the local currency raised would go towards conservation.

Unlike previous debt swaps driven by a profit motive and giving multinationals “equity” in a country, debt-for-nature swaps were supposed to benefit the debtor country. Lovejoy’s column is widely recognised as one of the “catalysts” for debt-for-nature swaps.

Three years later, in 1987, US-based Conservation International entered into the first-ever debt-for-nature agreement with Bolivia.

In exchange for the Bolivian government’s commitment to grant maximum legal protection to nearly 4m hectares in the Amazon Basin, Conservation International bought $650,000 worth of debt from a swiss bank for $100,000. Bolivia also agreed to provide $250,000 in local currency for management activities in the Beni Reserve.

Even early proponents of debt-for-nature swaps acknowledged that they were “no panacea” for environmental issues in the least-developed countries. Nevertheless, they continued to be popular and have seen a resurgence in the post-Covid era.

How do debt-for-nature swaps work?

In its simplest sense, a debt-for-nature swap involves:

- An indebted, biodiverse developing country.

- A creditor or a group of creditors, such as other governments or private bondholders.

- International conservation organisations, to buy back the debt.

- Local conservation organisations, to implement the swap.

International conservation organisations or private foundations based in the global north have initiated or brokered most debt-for-nature swaps.

Other actors and intermediaries involved in swaps can include commercial banks, multilateral development banks, private finance institutions, insurance companies and legal and financial advisors.

Today, there are many different kinds of debt-for-nature deals in progress, but swaps can broadly be classified as “private”, involving commercial debt, or “public”, involving the debt between governments.

Private debt swaps

In private debt swaps, NGOs offer to buy back part of a government’s commercial debt from private creditors at a significant discount compared to the debt’s face value.

The indebted country then commits to repaying this debt – in whole or in part and generally in local currency. The amount generated by this payment – the difference between the price paid in local currency and the discounted price the NGO buys the debt for – is then put into an environmental protection fund administered by the conservation NGO.

While this was the model for most debt-for-nature swaps until 2008, arrangements have grown more complex in recent years.

The “buy-back” of debt claims by NGOs, for instance, has grown to take the form of various kinds of bonds – essentially, an IOU or loan issued by a government or company, whereby the issuer promises to pay back the face value of the loan on a set date, with regular interest.

For example, the Nature Conservancy set up a trust fund in 2015 which issued a $15.2m “blue bond” that private philanthropic funds paid into. This sum was then lent to the Seychelles government, which used it to buy back $21.6m of debt from the Paris Club of developed country creditors.

In exchange, Seychelles pledged to protect 30% of its marine area and 15% of high-biodiversity regions, along with upgrading its marine mapping and fisheries policies.

Despite a total debt reduction of only $1.4m, the island state committed to investing $5.6m in marine conservation and $3m towards an endowment trust fund.

Public debt swaps

Swaps of debt between countries in exchange for conservation commitments are known as “public debt-for-nature swaps”.

Here, the indebted, biodiverse country restructures or buys back debt from a lender country at a reduced price. The interest or a percentage of the buy-back price then goes toward environmental protection.

The first such swap took place in 1988 between Costa Rica and the Netherlands to finance a 4,000-hectare reforestation programme.

These bilateral debt-for-nature swaps have seen a resurgence in the past year or so.

In January 2023, for instance, Portugal signed an agreement to swap up to $140m of Cape Verde’s debt for investments in a special environmental and climate fund, with more debt relief determined by how its former colony meets key climate and nature goals.

In September last year, the US and Peru entered into a swap agreement covering more than $20m of Peru’s debt to the US. The money will go towards a conservation fund to protect three priority areas in the Amazon rainforest and provide grants to local communities and NGOs.

How are swaps gaining traction in nature finance and conservation policy?

Since the 1980s, 145 debt-for-nature swaps worldwide have written off $3.7bn from the face value of debt globally, according to a 2022 report by the African Development Bank (AfDB).

Most of the debt swaps – $2.4bn of the total – have occurred in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Carbon Brief has compiled a list of debt swaps that have taken place around the world. This is based on data from the African Development Bank report, along with reports from governments, conservation organisations and the media. It is not an exhaustive list.

The map below shows where swaps have taken place. The circles indicate the financial size of the debt involved in the swap, while the colours show the decade in which the swap was completed.

At the COP15 climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009, debt-for-nature swaps featured at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change for the first time. They were included in the negotiating text after Indonesia introduced “external debt swap/relief” as a source of finance.

At COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022, the Sustainable Debt Coalition Initiative was established with the support of 16 countries. It asked for debt swaps and other mechanisms to tackle both climate change and financial stability concerns.

At COP28 in Dubai last year, eight multilateral development banks, including the Green Climate Fund and the Global Environment Facility, announced a working group to boost the effectiveness, accessibility and scalability of sustainability-linked sovereign finance, including debt-for-nature swaps.

In the announcement, the development banks acknowledged that the burden of debt owed by the developing countries “greatly hinder[s] their ability to meet their global climate and nature commitments”.

The debt issue is also being addressed in other international meetings.

During the April 2024 World Bank and International Monetary Fund spring meetings, the Vulnerable Twenty Group (V20) – made up of 68 heavily indebted, climate-vulnerable countries – called for additional reforms to the international financial system. They proposed several measures, including increased representation in the global financial system and greater access to concessional finance, or finance provided at lower interest rates than commercial finance, including debt-for-nature swaps.

Eva Martínez, a human rights lawyer and programme officer at the Centre for Economic and Social Rights (CEDES) in Ecuador, tells Carbon Brief that swaps will also feature at this year’s G20 summit in Brazil. She explains:

“There is a working document on the new financial architecture…There are [also] references to [debt swaps] for food sovereignty, debt-for-health swaps. The spectrum is broadening.”

What are some of the chief criticisms of debt-for-nature swaps?

Since their inception, debt-for-nature swaps have attracted considerable concern over whether they are effective for either debt relief or conservation.

As with biodiversity offsets and nature-based solutions, debt-for-nature swaps have been criticised for putting a price on nature and “reducing” it to a financial commodity.

Another complication is that “biodiversity is really cheap”, Dr Rebecca Ray from Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center tells Carbon Brief. As a result, creating and maintaining new protected areas is often a small fraction of a country’s sovereign debt. She adds:

“This means a little bit of debt swapped goes a really long way to fund new natural protected areas, but it doesn’t go very far on the debt. And so it’s not the most efficient way to discharge debt, even though countries are particularly facing debt stress right now.

”Repaying debt is hard for countries all around the world due to problems that are not their fault.”

These countries need “immediate debt relief that is fast and large”, Ray points out, but biodiversity conservation projects “tend to cost a lot less money and take a lot more time”.

The following sections provide an overview of some of the other criticisms of debt-for-nature swaps.

Conditionality, sovereignty and additionality

The earliest controversy around debt-for-nature swaps was a perceived fear of foreign interference, sovereignty and a “return to the colonial system”.

The first swap in Bolivia in 1987, for instance, “unilaterally titled” the land to be protected in the Amazon before Indigenous communities could obtain land tenure claims. In 1989, Brazil’s then-president Jose Sarney rejected debt-for-nature swaps stating: “[The] Amazon is ours… [a]fter all, it is situated in our territory.”

Entering into a debt-swap agreement “immediately results in a loss of autonomy and sovereignty” over the resolution of public debt, argues Mae Buenaventura, senior programme manager on debt and green economy at the Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development (APMDD). She tells Carbon Brief:

“Lenders determine the terms of the swap, meaning that they can impose conditions on borrowing governments on how they should invest the freed-up funds and can work towards privileging the lender and private corporations.”

This, Mae and other critics say, gives lenders in the global north “more control” in a developing country than if the debt were to be cancelled outright.

They point out that debt-for-nature swaps also inherently come with conditions attached for conservation measures and can, thus, be described as conditional debt relief.

Others fear that swaps could open the door to “tied-aid” methods, where aid must be spent on services from the lending country, such as swaps being coupled with carbon credits.

However, Ray sees significant evolution in governments’ and creditors’ understanding of the need to put traditional communities that depend on biodiversity front and centre in the planning process.

She cites the success of the 2015 Seychelles debt-for-nature swap, where the Seychelles government undertook a multi-year “deep consultation” process to understand threats to the livelihoods of small fishing communities living on remote islands. Ray says:

“This was a way that got community buy-in, obviously, because this was protecting the livelihoods of those fishing communities, but also recognising that traditional communities frequently don’t just live off of biodiversity, but they have to help protect the biodiversity in order to survive.”

Another criticism of swaps is that they do not create new, “additional” biodiversity funds from the global north. They also run the risk of being “double counted”, if the original loan being restructured in a swap had already been counted towards meeting aid targets.

Frederic Hache, co-founder of the independent thinktank of the EU Green Finance Observatory, tells Carbon Brief:

“The reality is that no global-north country has any intention of dispersing significant amounts of new grant money…All you get is these conditional financial instruments designed to benefit primarily global private investors.”

Scale, fees and forgiveness

The biggest criticism of debt swaps from all the experts Carbon Brief spoke to is their size relative to the looming sovereign debt of biodiversity-rich countries.

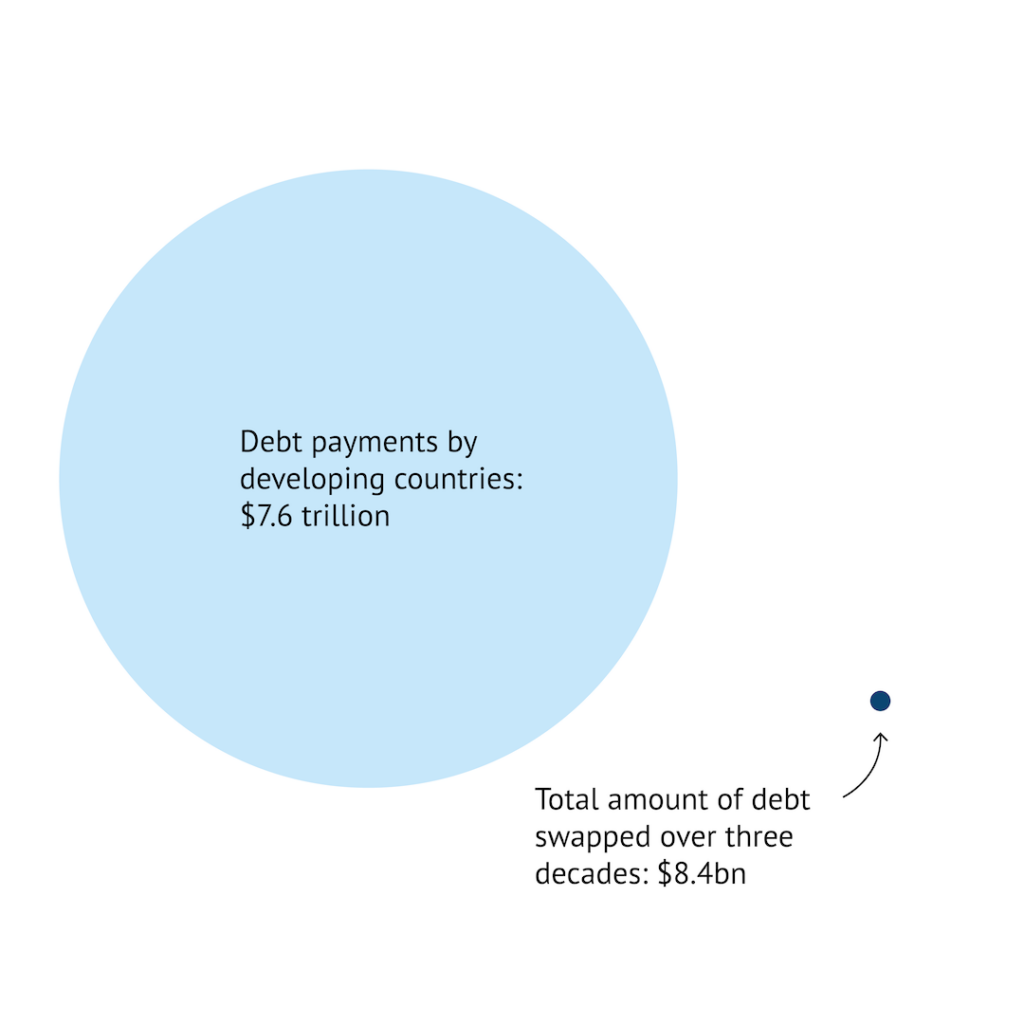

The graphic below compares the size of debt swaps (small, dark blue circle) to the amount that indebted developing countries have paid to service their debts (large, light blue circle) over the past three decades.

The Seychelles marine biodiversity swap, for instance, was considered “one of the largest in history at the time”, but only amounted to $23m. Ray says:

“That’s pennies, in comparison to the billions of dollars that countries like Sri Lanka are currently negotiating for debt restructuring…[Swaps] only make sense as part of a broader package of debt relief to meet the current crisis.”

According to Prof Jayati Ghosh, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, while debt swaps imply debt reduction, they “are far too small to have any impact at all” on countries’ debt. Sometimes, she says, swaps are not even a reduction, but instead allow countries some leeway in rescheduling their debt payments. Ghosh adds:

“It’s not even rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. It’s pretending to rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic, with big creditor countries refusing to really make the kinds of interventions that would make a difference in reducing the sovereign debt while pretending to do something about climate and conservation finance. And they’re not.”

According to Carbon Brief analysis, among all the debt-for-nature swaps that have taken place, Poland’s 1992 swap allocated the highest amount of resources to nature conservation, totalling over $500m. Ecuador’s 2023 swap, which saw the largest amount of debt swapped at $1.1bn, had the second-highest investment in conservation, allocating more than $400m for this purpose.

The chart below shows the 20 countries that have been the target of the largest debt swaps (light blue) and the amount of that money earmarked for conservation funds (dark blue).

High transaction costs, which are driven up by lengthy, complex, multilateral negotiations, the number of agents involved and intermediary fees, also eat into conservation savings.

Others point out that other real-world challenges, such as unstable exchange rates along with high inflation, can “erode and undermine the real value” of a country’s conservation commitments. For example, in Zambia, funds generated by a $2.2m debt swap in 1989 were exhausted in a year “due to the rapid devaluation” of the local currency.

Human rights

Sandra Guzmán, founder and general coordinator of the Climate Finance Group for Latin America and the Caribbean (GFLAC), tells Carbon Brief that it is not possible to generalise the impacts of debt-for-nature swaps. She adds:

“A swap with the World Bank, a swap with the IDB [Inter-American Development Bank] or a swap with a commercial bank is very different. Not all swaps are done in the same way because it depends on the institutions involved.”

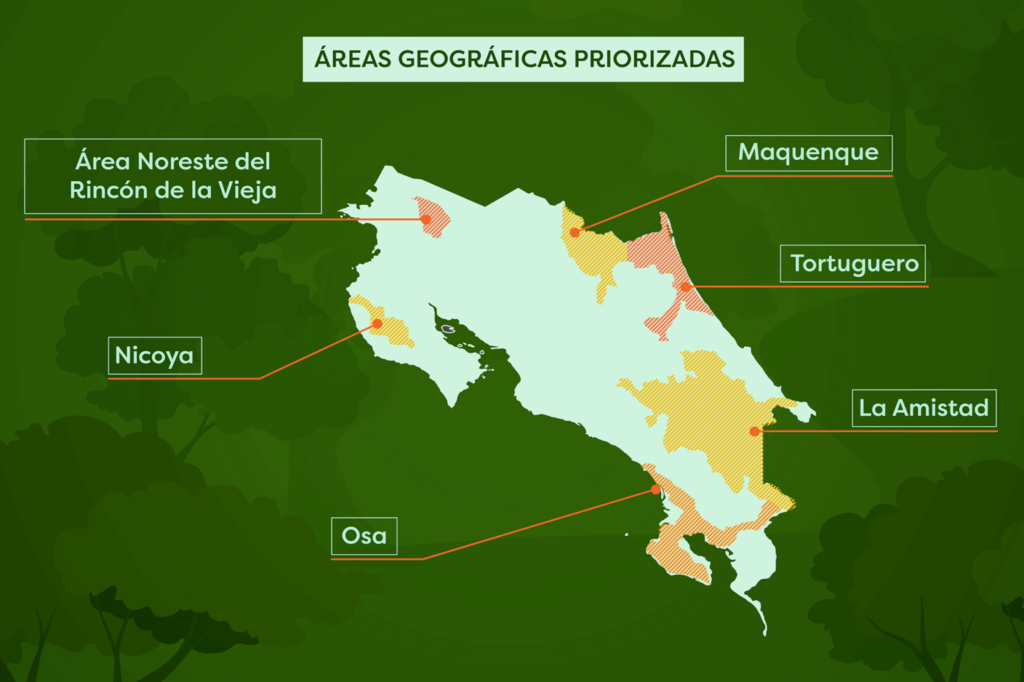

The 2007 debt-for-nature swap between Costa Rica and the US is an example of a swap where public information on its activities in Indigenous and local communities is available.

This swap involved more than 200 rural communities. One of the projects in the KéköLdi Indigenous territory, in south-eastern Costa Rica, helped the community reintroduce native iguanas and transmit ancestral knowledge to youth. Guzmán tells Carbon Brief:

“It has been said to be one of the most effective [swaps] because of the size of the debt cut and the conservation programme that Costa Rica promoted.”

However, not all debt-for-nature swaps have been so clear about the impacts on Indigenous and local communities.

Martínez, of CEDES Ecuador, tells Carbon Brief that the Galapagos debt-for-nature swap – signed last year to cancel $1.1bn of Ecuador’s debt in exchange for investing $450m to protect Galapagos islands – did not undergo a consultation process with Indigenous peoples and local communities. This could impact the economic, social, cultural and environmental rights of these communities, Martínez said.

The Climate Bonds Initiative published a report in 2023 analysing debt-for-nature swaps in the Seychelles, Belize, Barbados and Ecuador.

Daniel Costa, senior sustainability debt analyst at Climate Bonds Initiative, tells Carbon Brief that most of the analysed swaps do not mention how they involve local communities. He adds:

“This is what we would like to see further as these transactions are developed.”

Governance

Other criticisms of debt-for-nature swaps are the inadequate governance conditions that debtor countries may have. Governance refers to how swaps are implemented in the countries, the institutions and stakeholders involved and the structure of negotiations.

For example, the 2023 Galapagos swap had “serious limitations” in monitoring and enforcement, lack of transparency and accountability and “little clarity on potential fiscal risks for Ecuador”, according to recent analysis by the Latin American Network for Economic and Social Justice (Latindadd) and other organisations.

The analysis also revealed a lack of public information on the conservation fund and whether these actions have contributed to capacity-building at the local level.

The decision on which conservation activities will be implemented with a debt-for-nature swap varies from transaction to transaction, notes Costa, of Climate Bonds Initiative. These activities are often managed by funds, whose members include conservation organisations in addition to the government, he adds.

Carola Mejía, climate justice, transitions and Amazon coordinator at Latindadd, tells Carbon Brief that while swaps may be potentially scalable, they need to be improved in many ways. She says swaps must be built on principles such as transparency, respect for sovereignty and fairness in negotiation.

Guzmán, of GFLAC, tells Carbon Brief:

“Not all countries will have the same capacities in terms of governance, structures, human, financial and institutional capacities. There are severely indebted countries that need [debt] cancellation; there are countries that can do swaps because they have economies that can move towards those scenarios; and there are countries with greater financial capacity that may not [need] swaps, but other types of financing.”

Greenwashing

Civil society organisations and researchers have also raised concerns about the potential for “greenwashing” in some debt-for-nature swaps.

Mejía says countries in the global north are not meeting their climate finance and biodiversity commitments, but are promoting swaps as “the big solution”. This carries the risk of greenwashing, Mejía adds, as rather than creating positive action for the environment, swaps are generating more loans and debt.

For example, the $30m swap between Indonesia and the US made in 2009 in exchange for conserving rainforests on the island of Sumatra had several shortcomings, according to a 2011 study. The swap did not free up additional resources for the Indonesian government and was “too insignificant to create indirect (positive) economic effects”, the study says.

In the 2023 Galapagos swap, although the IDB provided an $85m guarantee to support the debt agreement for 18.5 years, the Latindadd report found that “there have been no additional international commitments or disbursements so far”.

Debt-for-nature swaps have also been questioned for not directly benefiting citizens and for transferring power over the management of the funds and the implementation of conservation projects to creditors.

The Gabon Blue Conservation was created as part of the swap where Gabon received $500m in exchange for protecting 30% of its oceans. This foreign-owned conservation organisation receives a 20% administration fee, which “immediately reduces the savings for the country by a [fifth]”, a report by the Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements says.

Moreover, the report adds, “it is hard to see evidence that” the marine spatial plan, mandated by the Nature Conservancy for this swap, empowers marginalised groups, including fishers, for decision-making around coastal management.

Hache tells Carbon Brief:

“From a geopolitical perspective, swaps are great. It’s a way to gain access and control to land resources that will prove possibly precious in the future. This is…diplomacy by other means.”

Can debt-for-nature swaps be more effective?

Debt-for-nature swaps are being reviewed for their effectiveness again at a time when biodiverse, developing countries struggling with debt payments are having to find the financial resources to meet biodiversity and climate targets.

According to the latest World Bank debt report, low- and middle-income countries owed their foreign lenders $9tn in 2022. The same year, these countries paid a record $443.5bn to pay down these debts, with these payments diverting government spending away from critical development priorities, as well as climate and nature spending.

A 2023 study found that 67 countries at risk of defaulting on their loans collectively host 22% of global “biodiversity priority areas”, such as relatively intact but vulnerable forests, grasslands, deserts and mangroves. For 35 of these countries, it estimated that all of their unprotected biodiversity priority areas could be protected for a fraction of their national debt.

Debt-for-nature swaps and debt-for-climate swaps could free up more than $100bn of debt in developing countries, according to a recent analysis by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

Ray, from Boston University, says that swaps can help create space for countries to make climate-adaptation plans that also help preserve livelihoods that depend on biodiversity, such as fishing or collecting forest produce.

She adds that this can “interrupt a vicious cycle between natural capital and volatile financial capital”, where economic crises and extreme weather events drastically reduce climate adaptation and biodiversity budgets.

But, in order to create this breathing room for biodiversity, swaps need to accomplish multiple things, she tells Carbon Brief:

“You need a lot of time. You need political capital and institutional capacity to centre the communities who have traditionally been the stewards of biodiversity and find a way to make sure that not only is their access to biodiversity uninterrupted, but that they are accountable for that job and rewarded for it. And a real commitment to accountability from everyone involved to make sure these projects actually help support biodiversity and communities.”

Ray points to the case of “blue bonds” for marine conservation, a label that multinational bank Barclays called “misleading” in 2023. According to Barclays, while “the point of a green bond is that 100% of the proceeds raised are spent on” marine projects, in blue bonds floated, each extra party “takes a cut from the proceeds”.

Other experts Carbon Brief spoke to had differing views, suggesting that debt-for-nature swaps would not just require improvements in governance, but in reforming the architecture of international finance.

Guzmán says:

“[Swaps] are initially going to open up your fiscal space, but are not going to solve the financing problem for countries. What we need to fundamentally change is the operation of financial institutions and the type of loans and the conditions they give for those loans, i.e., lower interest rates and much more appropriate treatment. That is really what is going to help sustainable financing.”

To Ghosh, creditors are often “unwilling to make very large commitments of debt reduction”. She adds:

“You have to do something about sovereign debt on its own, which means you have to be serious about the debt reductions. That’s independent of whether you’re linking this conditionality with nature, because without dealing with the sovereign debt, you are not going to generate a green transition in any of these countries. They simply can’t afford it.”

Ghosh suggests solutions that could change the “landscape of debt”, including a standstill on debt during debt negotiations – where the amount of debt stays the same instead of accruing interest while parties come to a resolution – and involving all creditors: private, public and multilateral.

To Hache, the “devil lies in the details” of debt-for-nature swaps. He says:

“It’s about the proportion of the budget allocated to conservation. It’s about the real amount of debt forgiveness compared to where the debt was trading, compared to its nominal value earlier…Ultimately, you also have to compare it to the real alternative, which is debt forgiveness, and you kill any chances of debt forgiveness, loss and damages by endorsing or accepting these deals.”

-

Q&A: Can debt-for-nature ‘swaps’ help tackle biodiversity loss and climate change?