The Carbon Brief Profile: Russia

Anastasiia Zagoruichyk

09.22.22In this country profile, Carbon Brief examines the state of climate and energy policies in Russia, home to some of the world’s largest reserves of coal, oil and gas.

Russia is currently the fourth largest greenhouse gas emitter behind China, the US and India. In addition, it is the world’s third-highest carbon emitter in history, responsible for some 7% of global cumulative CO2.

The nation relies heavily on revenues from oil and gas exports, which in 2021 made up 45% of its federal budget.

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia was the EU’s largest source of imported energy, supplying 41% of the bloc’s gas needs, 27% of its oil and 47% of its coal.

It has the world’s seventh-largest fleet of coal-fired power stations but less wind and solar capacity than its neighbour Finland, a nation with a population 26 times smaller. However, Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, calls the nation’s energy mix “one of the cleanest and low[est]-carbon in the world”, thanks to its large nuclear fleet and extensive hydropower.

Last Autumn, Putin announced that Russia “will strive” for carbon neutrality by 2060 – its most ambitious climate goal to date.

Around two-thirds of Russia is covered by permafrost – permanently frozen ground that never normally thaws, even during summer. As global temperatures rise, this permafrost has the potential to release large stores of greenhouse gases.

Russia is already experiencing severe impacts from climate change, such as intense and frequent wildfires, especially in Siberia.

Due to the vast scale of its mineral resources and agricultural productivity, Russia could become “a pivotal stakeholder in global climate action”, some researchers say. However, its leaders have so far shown little willingness to set ambitious climate policies.

- Politics

- Paris pledge

- Gas, oil and coal

- Methane emissions

- Nuclear

- Hydro

- Heat production

- Renewables

- Climate policies and laws

- Impacts and adaptation

Politics

Russia is the largest country in the world, with a territory covering 17m square kilometres across the whole of northern Asia and much of eastern Europe. However, it is home to only 143.4 million people – fewer than Nigeria.

Russia, also officially known as the Russian Federation, is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects.

The country has the world’s 11th largest economy, with a GDP of $1.5tn in 2020.

The first article of the Russian constitution states that “Russia is a democratic federal law-based state with a republican form of government”. However, one of the cornerstones of democracy is a regular turnover of power, which has not happened in Russia under the current president, Vladimir Putin.

Putin has occupied this role for 10 years, since 2012. Prior to this, he had already served as president for eight years until 2008, switching places with his prime minister Dmitry Medvedev for four years.

This switch was due to restrictions on term length, which have since been abolished.

Putin is the de-facto leader of the largest conservative Russian political party, United Russia, which gained almost 50% of the votes in the 2021 parliamentary elections.

Russia has a permanent legislative body, the Federal Assembly or parliament, which consists of two chambers: the State Duma and the Federation Council.

The State Duma consists of 450 members or deputies, who are elected by the Russian citizens “on the basis of universal equal and direct suffrage by secret ballot”.

The Federation Council is the upper chamber of the parliament, which is composed of two representatives from each of Russia’s administrative divisions.

Human rights and democracy research organisation, Freedom House, describes the Russian political system as “authoritarian”, which includes a “controlled media environment, a legislature consisting of a ruling party, pliable opposition factions and manipulative elections”.

Russia has been one of the slower countries to act on climate change. It took Moscow two years to ratify the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), seven years to ratify the Kyoto Protocol and four years to ratify the Paris Agreement.

At a press conference in 2019, Putin claimed that “no one knows the true cause of climate change”, adding that calculating how humanity affects global climate change “is very difficult, if not impossible”.

(Scientists estimate that humans are responsible for 100% of current warming.)

Even while facing the visible consequences of climate change, Russia still avoids recognising it as a threat. In December 2021, it vetoed a UN Security Council resolution that warned about the international security implications of the climate crisis. The country’s ambassador said the resolution was “unacceptable” for his government and that it would turn the climate crisis into “a politicised question”.

Meanwhile, Russia has taken a different approach in its public communications, with Putin’s senior climate adviser, Ruslan Edelgeriyev, making statements for several years about the importance of taking urgent actions toward climate change, including taking more substantive steps to reduce the nation’s dependence on fossil fuels. He has pointed to natural disasters, such as widespread wildfires in Siberia, as a sign that Russia must act.

At the same time, the head of the second most popular party in Russia, Gennady Zyuganov, openly declares his climate scepticism. His Communist Party won 19% of the vote during elections to the Russian parliament, the State Duma, in 2021.

In an appeal published on the party’s website in 2022, Zyuganov was quoted saying:

“The reshaping of the modern world in favour of transnational evil goes through attempts to drive our country into the race for the so-called green agenda. The fact that the climate is changing has long been known. It changes cyclically and the reasons here are natural and not entirely man-made.”

Polling conducted in 2020 by the Russian public opinion research centre found that “40% of adult Russians believe that the problem of global warming is far-fetched and inflated”.

A 2022 study notes the presence of “a discernible climate sceptical narrative in Russia with many similarities to climate scepticism in the US, but also much specificity and distinctness”.

The researchers found that Russian scepticism is not, as in many other nations, a reaction to a mature, developed environmental movement, with a vocal presence in public and media discourse. Instead, they describe it as a result of elites’ influence, guided by the “Soviet-era notion” that the power of progress can solve any environmental problems.

Although some Russian scientists have publicly opposed the science of anthropogenic climate change, others have contributed to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, suggesting their positions correlate more with mainstream climate science.

Paris pledge

Russia’s emissions in 2019 were 1.92bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e), according to the CAIT database maintained by the World Resources Institute (WRI), which includes emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF).

Ahead of the negotiations that finalised the Paris Agreement in 2015, Russia presented a climate pledge (nationally determined contribution, NDC), promising that by 2030, its emissions would be 25-30% lower than levels registered in 1990.

However, as of 20199, its emissions were already 2828% lower than in 1990, due to the economic decline that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992. This means that it can meet its target with minimalwith minimal emissions reductionsreductions.

In 2019, Russia ratified the Paris Agreement, formalising its international commitment in national policy.

Signing the ratification, then-prime minister Dmitry Medvedev noted that “the most important thing is the threat to the security of people who live in permafrost conditions, as well as the increase in the number of natural disasters”.

Nevertheless, Russia’s vague climate pledge and its delayed ratification of the Paris deal means there has long been scepticism over its true commitment to tackling warming. An Asia Times article responding to the ratification called it a “zero-cost PR move”.

Ahead of COP26, the Russian government approved a strategy for “low-carbon development” with a goal of achieving carbon neutrality no later than 2060.

On 5 September 2022, Russia submitted its long-term low-emissions development strategy to the UN, under the Paris Agreement, with the document confirming a goal – agreed at national level in 2021 – of cutting emissions 80% by 2050 on 1990 levels.

However, in an article for Energy Transition, journalist Paul Hockenos argued that “the real motivator prompting Russia to formulate goals and begin decarbonisation is the fear that its trade market – in particular, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilisers, cement and electricity – will suffer when the CBAM [carbon border adjustment mechanism due to be implemented by the EU] goes into effect in full in 2026”.

The CBAM is a proposed CO2 tariff which would start in 2026 and force some companies importing into the EU to pay carbon costs at the border on carbon-intensive products, such as steel and aluminium.

Russian media has reported that the country will become “the main victim of the carbon tax”, referring to a report by the thinktanks Sandbag and E3G that concluded “imported goods from Russia will face the greatest CBAM fees”.

Russia’s updated climate pledge, submitted in November 2020, aims to keep emissions 30% below 1990 levels by 2030, compared to the initial pledge of 25-30%.

The update was rated as “critically insufficient” by Climate Action Tracker, which said it did not represent an increase in ambition as “it is simply the lower bound of the previous target’s range”.

Moreover, in its current NDC, Russia says its emissions target includes “the maximum possible absorptive capacity of forests and other ecosystems”. In other words, its target will rely heavily on nature-based solutions to absorb emissions rather than necessarily requiring significant cuts in fossil-fuel use.

In September 2022, a group of activists filed the first-ever climate lawsuit against the Russian government, demanding stronger action on meeting Paris accord goals.

During the COP26 UN climate talks in Glasgow, Russia joined the “Glasgow leaders declaration on forests and land use”. This agreement includes a commitment to protect and restore forests.

Putin did not attend Glasgow personally, leaving a recorded appeal to just one of the summit sessions on forest and land management.

Shortly before the climate talks in Glasgow, Russia’s prime minister Mikhail Mishustin said:

“The global economy is focused on a gradual transition to low-carbon energy. This is already a new reality. We need to prepare for a phased reduction in the use of traditional fuels – oil, gas, coal.”

However, Russia’s gas production has actually been growing. Last year’s gas output reached an annual record of 763bn cubic metres.

Despite the ongoing war, the country’s oil output has climbed back to near pre-war levels, averaging almost 11m barrels per day in July 2022.

Russia, as a party to the UNFCCC, participates in negotiations as a member of the Umbrella Group, a block of non-EU developed countries.

However, the group announced that, “in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the actions of Belarus to enable this, members of the Umbrella group are not coordinating with Russia and Belarus at this time”.

During the first UN climate negotiations since Russia invaded Ukraine, delegates walked out of a session where a Russian official was speaking.

Gas, oil and coal

Russia is the world’s second-largest producer of gas, behind the US, and has the world’s largest gas reserves, followed by Iran and Qatar, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Together, these three countries accounted for half of the world’s gas reserves in 2020.

Gazprom and Novatek are Russia’s leading gas producers, but many Russian oil companies, including Rosneft, also operate gas production facilities.

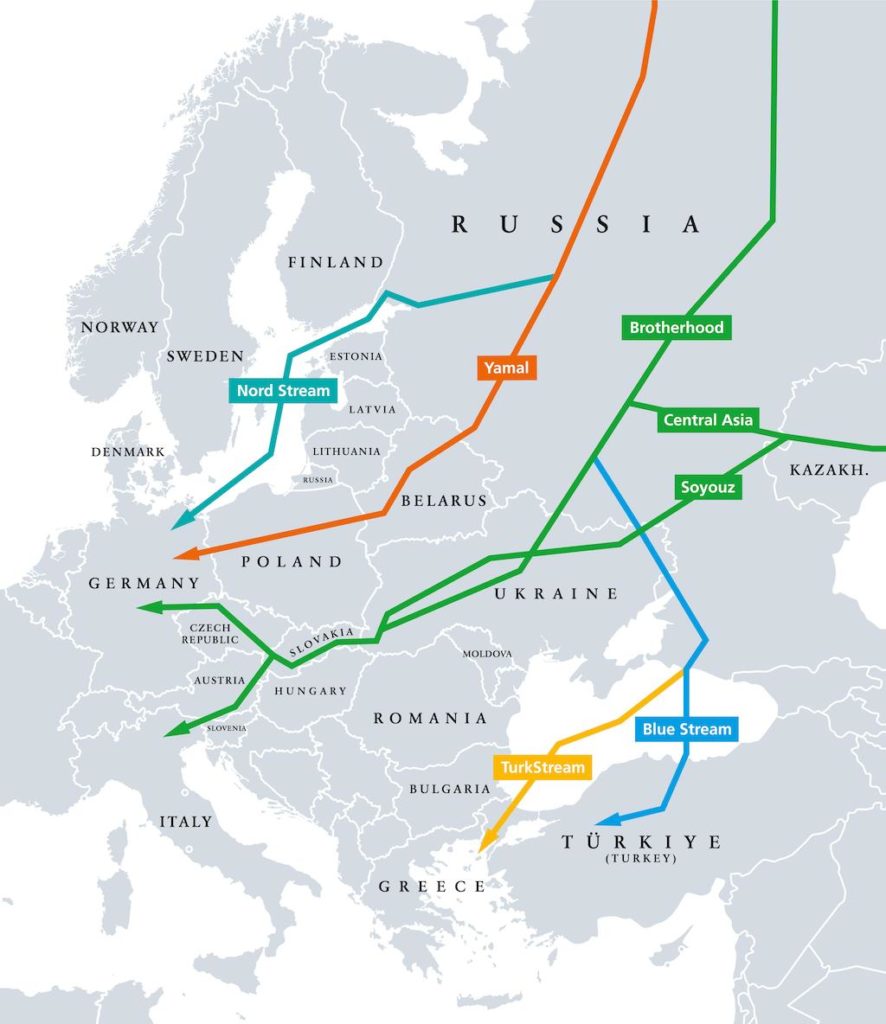

Russia owns the world’s second-largest gas infrastructure after the US, including pipelines with a total length of almost 100,000km.

Some of the world’s largest gas fields are located in Russia. For example, ranking second globally by capacity and size is the Urengoy gas field located in the north of the western Siberia basin. Russia’s Yamburg gas field ranks third.

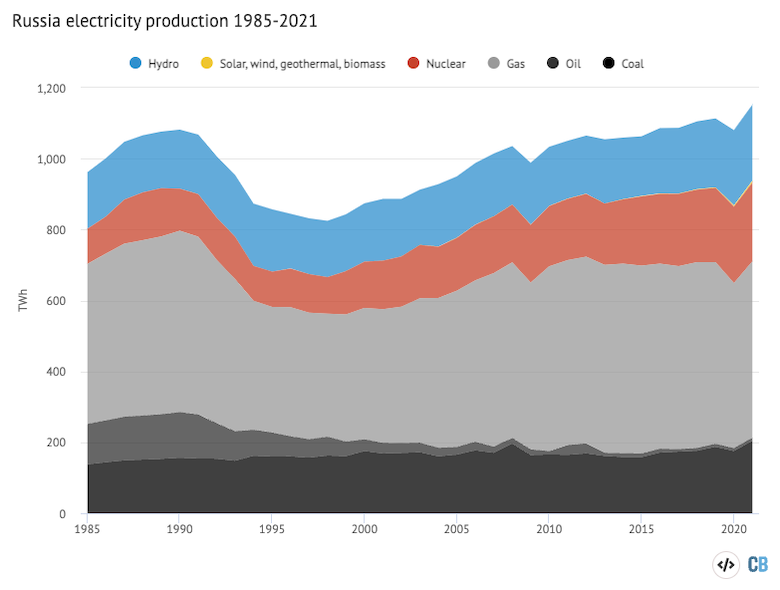

Gas is Russia’s main electricity source, providing 43% of power in 2021, while coal and oil provide 17.7% and 0.7%, respectively. Nuclear accounts for 19.3% and hydro another 18.6% of electricity supplies, with non-hydro renewables pulling up the rear with 0.4%.

Russian crude oil and condensate production accounted for 14% of global supply in 2021, making Russia the world’s second highest exporter of crude, after Saudi Arabia.

The major infrastructure for transporting Russian gas and oil to European countries are the Baltic pipeline system, Druzhba oil pipeline, Yamal-Europe, Urengoy-Pomary-Uzhgorod (Soyuz and Brotherhood), Nord Stream 1, Blue Stream and Turkstream gas pipelines. The gas pipelines are shown in the map below.

However, gas deliveries through Europe’s main pipeline, Nord Stream 1, were brought to a halt by Gazprom indefinitely on 2 September 2022. Gas deliveries had already been cut significantly starting in 2021, with exports to Europe down 45% in 2022 to date.

Russia has the second largest coal reserves in the world, less than the US but more than Australia.

The country plans to increase its domestic coal production to 530m tonnes annually by 2024 and to 668m tonnes annually by 2035, according to its Energy Strategy, which was adopted by the government in April 2020.

In 2021, Russian environmental group Ecodefense jointly with German partner group Urgewald published a report detailing the massive environmental impact of coal mining in the Kemerovo Region, also called Kuzbass – an area in south-west Siberia where up to 70% of Russia’s coal is mined. Most of the coal produced is shipped to Europe and Asia.

Russia provided the EU with 39% of its gas and 25% of its oil in 2021.

As by far the largest supplier of oil, gas and coal to the EU, Russia had received almost €90bn in fossil-fuel payments from its European neighbours since the war began, as of September 2022.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has highlighted this dependence and has prompted the EU and its allies to try to end the use of Russian imports.

As a result, the European Commission has released its REPowerEU strategy that sees gas consumption in the EU falling by two-thirds and imposed sanctions on the “purchase, import or transfer into the EU of crude oil or petroleum products originating in Russia or being exported from Russia”.

Additionally, on 11 August 2022, an EU ban on Russian coal imports came into force.

Europe still relies on Russian gas amid fears of cold winters without it. However, the nation is no longer considered “a reliable energy partner” after Russia completely halted gas supplies to Europe via a major pipeline, saying repairs were needed.

Andriy Yermak, chief of staff to Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelenskiy, has accused Russia of conducting “gas blackmail”.

At least 48 nations imported crude oil from Russia in 2019. The countries that rely on Russian oil the most are Belarus, Cuba, Curacao, Kazakhstan and Latvia – each importing more than 99% of their crude oil from Russia.

The countries that rely most on Russian oil include: Belarus, Cuba, Curacao, Kazakhstan and Latvia – each importing more than 99% of their crude oil from Russia.

— Al Jazeera English (@AJEnglish) March 11, 2022

🔗: https://t.co/yTiSDSCuDL pic.twitter.com/iKcWtVcmJs

The major markets for Russian coal will continue to be the Asia-Pacific states, south-east Asia, the Middle East and Africa, according to its Energy Strategy 2035.

Russia is attempting to diversify its exports including via a new pipeline to China called the Power of Siberia. According to S&P Global, by 2023, nearly 40% of Chinese gas demand growth will be met through Russian gas from the Power of Siberia.

However, the Chinese route cannot take gas that currently goes to Europe due to geographic separation.

“Russian authorities and businesses are short-sighted”, Sergei Bobylev, an economics professor at Moscow State University specialising in sustainable development, told the Moscow Times. “Our economy is based on companies like Lukoil, Gazprom, Rosneft, etc. And the prognosis for them isn’t looking very good”, he said.

Methane emissions

According to the IEA’s global methane tracker, Russia is the second biggest source of global energy-related methane emissions.

The country’s gas infrastructure, including production facilities and pipelines, is notoriously leaky despite calls for the government to take action. There are also significant methane emissions from Russian coal mines.Ahead of the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, the US and the EU launched a global methane pledge that aims to reduce methane emissions nearly a third by 2030. Nine of the world’s top 20 emitters have signed onto the effort. Russia did not.

Prior to the talks, the White House’s chief climate negotiator, John Kerry, had “spent hours” with top Russian officials in search of a “road map” to address the methane problem. In a joint statement in July 2021, the two nations declared an intent to cooperate on a wide range of climate issues, including limits on methane and the satellite monitoring of emissions.

However, Russian presidential envoy on climate Edelgeriyev insisted that the global methane pledge would impose an unacceptable burden on Russia. He later stated that Russia would “determine its own schedule for reducing methane emissions”.

Although Russian gas companies Gazprom and Rosneft are members of the voluntary reporting standard “Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0”, international experts have questioned the transparency and consistency of Russia’s governmental and corporate emissions reporting.

This issue was investigated in detail by the Washington Post and Environmental Defense Fund researchers in 2021, using satellite monitoring of emissions.

In national emission inventories and reporting to UNFCCC Russia has repeatedly revised its oil-and-gas methane emissions since its first 2006 report, with numerous changes in accounting methodology and data.

In the 2021 report, recalculations showed that the numbers were 90% lower than reported previously.

In May 2021, expert reviewers at the UNFCCC questioned this revision, saying Russia “did not provide information on the significant decrease in the level of [methane] emissions” caused by its recalculations.

Anna Romanovskaya, director of the government-linked Institute of Global Climate and Ecology, said the shifts in reporting of emissions were “a result of analysis of new data on methane emissions obtained directly from companies in the oil-and-gas sector”.

Analysing satellite data for 2019-2020, European Space Agency researchers discovered 46 large methane sources from Gazprom pipelines in Russian territory.

According to data firm Kayrros, total Russian methane emissions in 2020 increased by 40% compared to 2019, despite the drop in energy consumption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and a reduction of Russian gas supplies to the EU by approximately 14%.

The large emissions detectable from satellites are estimated by Kayrros to be only 10-15% of all methane pollution from the country’s fossil fuel industry. Satellites have limited capacity to detect small leaks due to their insufficient resolution.

A 2019 study by the US National Energy Technology Laboratory found that Russian gas piped to Europe emits more greenhouse gases than European coal which has been mined domestically.In June 2022, private satellite monitoring company GHGSat released data on methane emissions from the Raspadskaya Mine in the Kemerovo region in southern Russia, in what has been described as the biggest leak of methane ever detected from a single facility. Raspadskaya is the largest coal mine in Russia.

Our satellites measured 13 distinct methane plumes during a single pass, ranging in size from 658 to 17,994 kg/h 🛰️ If the total rate of release were sustained over a year, the mine would emit 764,319 tonnes of CH4 – enough to power 2.4m homes 🏡https://t.co/KimDwaUSJ4 pic.twitter.com/rVmBNdbjBi

— GHGSAT (@ghgsat) June 15, 2022

More recently, satellite images have shown that Russia has been burning off large amounts of gas, which originally had been intended to export to Germany.

Nuclear

Russia is the fourth biggest nuclear power user, with 28.7 gigawatts (GW) of installed capacity in 2021. This is as much as Japan, Canada and Spain combined.

Nuclear power ranks second after gas in the Russian electricity mix. In 2021, total electricity generated in nuclear power plants in Russia was 19.4% of all power generation.

In Russia, atomic energy is completely state-owned. It is run by the state corporation Rosatom, which operates 11 nuclear power plants in Russia with 37 reactor blocks, plus the Akademik Lomonosov floating nuclear power plant at Chukotka, with two small reactors.

The latest Federal Target Programme envisages a 25-30% nuclear share in electricity supply by 2030, 45-50% by 2050 and 70-80% by the end of the century. Eight reactor units are now under construction, to be completed by 2030.

Today, 10 identical reactors to those used at Chornobyl nuclear power plant are still operating in Russia.

Rosatom plans to decommission them gradually by 2035, but emphasises that the final dates will depend on “the dynamics of supply and demand in the market”.

All reactors of this type were built between 1976 and 1990, and they were designed for a 30-year service life. However, Rosatom has repeatedly extended their operation.

Vladimir Slivyak, the co-chair of the Russian environmental group Ecodefense, which was listed as a “foreign agent” by the government in 2014, argues that the main reason for extending the life of older reactors is “economic considerations”.

At the end of 2021, 15 Russian-designed reactors were under construction in other nations. In 2020, Rosatom’s package of foreign orders exceeded $138bn, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency.

The country is taking part in the construction of new nuclear power plants in nations including China, India and Iran. Agreements on the development of nuclear power production have been signed with Belarus, Finland and Hungary.

In July 2022, Russia signed a new construction deal for Turkey’s first nuclear plant.

Russia is an important source of uranium, the key ingredient in nuclear fuel. Europe gets some 20% of its uranium from Russia. The US relies on Russia for 16% of its uranium.

Russia owned 40% of the total uranium conversion infrastructure in the world in 2020 and 46% of the total uranium enrichment capacity in the world in 2018, according to a Columbia University report.

Russia also uses its nuclear capacity to threaten the world with the use of nuclear weapons.

In February 2008, Putin promised to target Ukraine with nuclear weapons if the US stationed missile defences there. In August the same year, he threatened a nuclear war if Poland hosted the same system. In 2014, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov warned that Russia would consider nuclear strikes if Ukraine tried to retake Crimea.

Soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, president Vladimir Putin said he was moving his “deterrent forces” – meaning nuclear weapons – to “combat ready” status.

Russia has the fourth largest electric power system in the world, preceded only by the US, China and India. The country’s total electricity generating capacity has been estimated to be about 243GW.

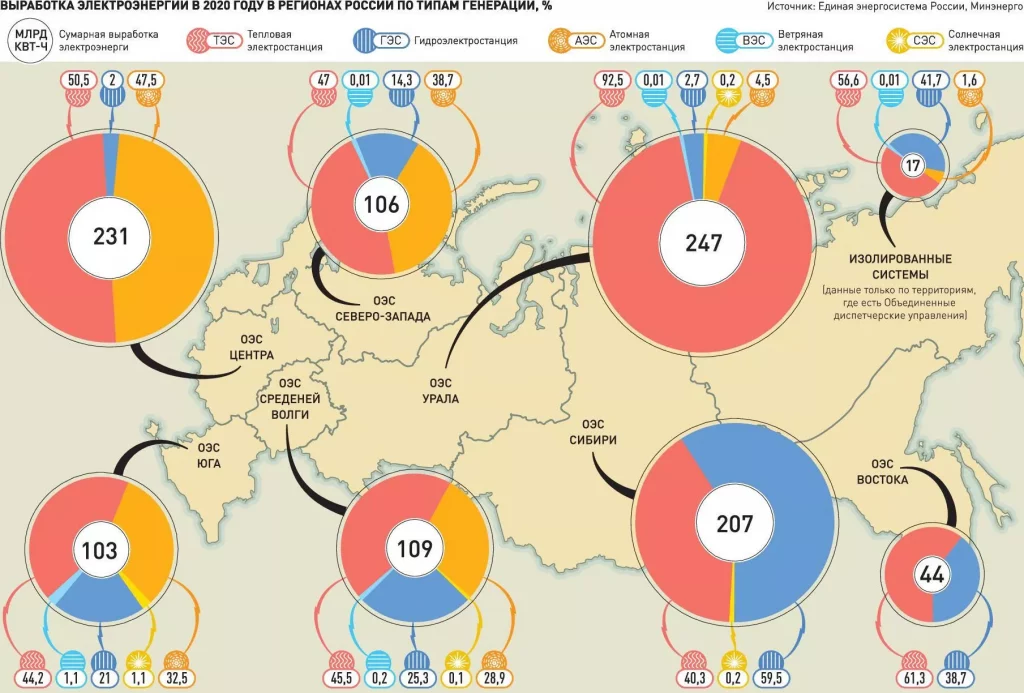

According to the Russian power system operator, the unified energy system (UES) of Russia consists of 71 regional energy systems, which, in turn, form seven unified energy systems: East, Siberia, Urals, Middle Volga, South, Centre and North-West.

The chart below shows how the Russian electricity balance worked in 2020. Each circle shows the electricity output of one unified system, with the size proportional to the generation in 2020 in terawatt hours (TWh). This is broken down by fuel type: gas, coal and oil are shown in red; nuclear in orange; hydro in blue; wind in turquoise; and solar in yellow.

Hydro

Russia was the seventh largest producer of hydroelectricity in 2021, according to a report by the International Hydropower Association.

Currently, there are 102 hydropower plants in Russia with a capacity of more than 100 megawatts (MW). The total installed capacity at Russian hydropower plants is approximately 45,000MW, according to a Russian state-owned hydroelectricity company RusHydro, which owns the majority of the hydropower plants in Russia, with around 80% of the country’s total.

As of 2020, hydropower was the only type of generation for which plans and mechanisms for further development have not yet been defined in Russia. The Energy Strategy until 2035 does not define specific directions or indicators for hydropower development.

Hydroelectricity provides 18.5% of Russian electricity, ranking third after nuclear.

However, the International Hydropower Association calls Russia “second in the world for undeveloped hydropower resources, with economic potential reaching 852TWh, and only 20% of it currently utilised”.

Heat production

Emissions from the building sector in Russia account for almost 9% of total CO2 emissions.

An IEA study published in 2011 comparing energy use in buildings across countries found that Russian residential buildings use more than twice as much energy to heat a square metre of space as those in Canada, a country with similar geographic and climatic conditions.

According to the Federal Statistics Service (Rosstat), in 2018, 70.6% of Russian houses were heated using centralised district heating, 21.9% by communal or individual boilers, 7.3% using stove heating, and 0.2% with underfloor heating, oil cooler etc.

In some regions, more than a third of families heat their homes with wood or coal. The highest share is in the southern Siberian region of Tyva, where 88% of families use stove heating.

Since 2016, according to an order of the Russian Ministry of Construction, each house in Russia has been assigned an energy efficiency class. To understand how much energy a building consumes, experts have identified nine classes: A++, A+, A, B, C, D, E, F and G, which is similar to the UK system.

“High-class” houses (A++, A+, A and B) can save 30-60% of resources due to thermal insulation and modern equipment. Usually, these are new buildings for which the future energy efficiency class is determined at the construction stage.

The “normal” energy efficiency indicator is D. A house with this class saves up to 15% of resources compared to the baseline level of energy efficiency of the house, which is defined by the number of storeys of an apartment building and “degree-days” of the heating period.

The “lowest class” is G, where the property loses about half of its heating resources.

In Russia, it is now forbidden to construct buildings with an energy efficiency class below B.

More than half of Russians (53%) consider energy efficiency an important factor when choosing residential real estate, according to a joint polling study by Dom.RF, a financial institution implementing government housing initiatives, and Russian public opinion research centre.

At the same time, only 11% of respondents who answered in the affirmative were sure that they understood well what the energy efficiency of housing is, while 42% said they had only heard “a little” about this concept.

Renewables

In 2021, 5.4TWh, or 0.4% of Russia’s electricity was generated from renewable sources, not counting hydropower, according to the BP Statistical Review of world energy.

“In Europe, crisis response plans have renewable energy and climate projects in the first place. In ours…we don’t see any ambitious plans to restart the Russian economy using carbon-free technologies or by investing into carbon-free projects”, said Alexey Zhikharev, director of the Association for the Development of Renewable Energy, reported by the Moscow Times in 2021.

Despite a Kremlin goal of producing 4.5% of Russia’s electricity from renewable sources by 2024, according to Zhikharev, the best-case scenario will only be 1%, even if every project now under development is completed on time.

Russia is “completely unprepared” for a world moving away from hydrocarbons and becoming increasingly committed to tackling climate change, said Tatiana Mitrova, professor and research director at the Skolkovo Energy Centre.

Before Putin began signing decrees aimed at cutting Russia’s emissions, he said that “when these ideas of reducing energy production to zero or relying only on solar or wind power are promoted, I think humanity could once again end up in caves, simply because it won’t consume anything”.

In 2019, he disparaged wind turbines, saying they “cause worms to come out of the soil”.

Despite this opposition, Russia’s vast geographical size, coupled with the varying climatic conditions and terrain, gives it an enormous advantage concerning developing any form of renewables, a study conducted in 2021 found.

The Black sea region, north Caucasus, the Caspian sea, Far East and southern Siberia are identified to have the highest solar energy potential.

Russia’s total solar energy capacity reached over 1.7GW in 2021, marking an increase from the previous year.

A 2021 study, citing research from 2015, put Russia’s technical solar potential at 19,000TWh per year – equivalent to two-thirds of global demand. It put the economic solar potential at justA 2021 study, citing research from 2015, put Russia’s technical solar potential at 19,000TWh per year – equivalent to two-thirds of global demand. It put the economic solar potential at just 102TWh per year, however, the cost of solar has declined dramatically in the last decade, so an up-to-date figure would likely be far higher, however, the cost of solar has declined dramatically in the last decade, so an up-to-date figure would likely be far higher.

The potential for the development of wind energy varies substantially across Russia. It is estimated to have a theoretical wind energy potential of about 197,477TWh per year and and a gross technical potential of about 21,850TWh annually.

Another study suggests Russia has a technical wind energy potential of 80,000TWh per year and an economic potential of more than 6,000TWh, which is roughly six times larger than the country’s current electricity demand.Another study suggests Russia has a technical wind energy potential of 80,000TWh per year and an economic potential of more than 6,000TWh, which is roughly six times larger than the country’s current electricity demand.

The most suitable areas for developing wind farms include territories of the north-west, territories of South and North Caucasus federal districts, Siberian, Ural, Far East federal district, Sakhalin Island, Kamchatka Peninsula, and coastal areas in the north-east of the country.

A report from the Russian Association of Wind Power Industry shows that, as of 2019, Russia had 564 wind turbines installed across the country, with an installed capacity of 191MW. For comparison, the wind capacity of Finland was 2,586MW in 2021.Geothermal energy exploitation in Russia has been carried out for the past 60 years. It is the second most commonly used renewable source in Russia. Geothermal energy is primarily used for heating purposes in many cities and communities in the northern Caucasus and Kamchatka.

Climate policies and laws

The Federal Law on Environmental Protection serves as the general foundation for environmental law in Russia.

It includes regulations protecting soil, water, plants and wildlife, standards for the maximum permitted concentrations of pollutants, and maximum permissible emissions of air pollutants.

There were no separate climate laws for a long time, except the Climate Doctrine, approved in 2009, which recognised that “the interests of the Russian Federation related to climate change are not limited to its territory, but have a global nature”.

The doctrine provided measures to improve energy efficiency in all sectors of the economy, introduce energy-saving technologies, expand the use of renewable energy sources and improve the fuel efficiency of vehicles.

However, many provisions of this doctrine remained only on paper.

The Federal Law on Limiting Greenhouse Gas Emissions was adopted in 2021. It created a state accounting system for greenhouse gas emissions and mandatory reports for large companies emitting more than 150,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent annually until 2024 and more than 50,000 tonnes after 2024.

However, it does not enforce emissions quotas or impose penalties on large carbon emitters.

The law also provides for the implementation of “climate projects” by companies and the issuance of “carbon credits” for their implementation.

Climate projects are understood as projects that ensure the absorption or containment of greenhouse gas emissions. The company can either redeem the carbon credits issued for its sale to reduce its carbon footprint or sell them to third parties.

Shortly before world leaders gathered for the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, the Russian government adopted a strategy for socioeconomic development with low greenhouse gas emissions until 2050 that foresees the country reaching carbon neutrality by 2060, which was submitted to the UNFCCC secretariat in September 2022.

The decarbonisation measures announced included: introducing low- and zero-carbon technologies, using “secondary energy resources”, changing tax, customs and budgetary policies, developing green financing, increasing the absorptive capacity of forests and other ecosystems, and supporting carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies.

The country also has decrees concerning the promotion of renewable energy and energy efficiency, whose targets have not been met.

In parallel with climate legislation, Russia has the above-mentioned Energy Strategy 2035 and the Coal Strategy 2035, both of which indicate that the government is fully committed to expanding the production and export of fossil fuels, plus that it has weak plans to transition to renewables.

Impacts and adaption

The IPCC report published in August 2021 listed “permafrost thaw” as a tipping point that could be reached within the next 50 years.

The frozen soil, which covers 65% of Russian landmass, holds hundreds of billions of tonnes of greenhouse gases, such as methane and CO2, which are released as it thaws. That is why some scientists call Siberia’s melting permafrost a possible “methane time bomb”.

The country could face $97bn in infrastructure damage by 2050 if the rate of warming continues, Mikhail Zheleznyak, director of Yakutsk’s Melnikov Permafrost Institute, told Reuters.

The most detailed study of Russia’s climate risks to date was published by Russian state meteorological service Roshydromet in 2017. All the expected consequences are described there – from the impact on human health to the impact on road surfaces.

According to Roshydromet, the warming of the climate in Russia is about 2.5 times more intense than the global average. The latest IPCC report describes the key consequences of climate change for Russia as increasing permafrost temperatures, deadly floods and forest fires.

It says that “the most destructive for Russia are floods, forest fires and abnormal heat”.

The heatwave of 2010 in the European part of Russia killed 56,000 people, as stated in a report by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR).

Wildfires that struck Siberia in 2021 were described as “bigger than all the world’s other blazes combined” during that period. Smoke from them reached the geographic North Pole for what could be the first time in recorded history, according to NASA.

Boreal forests – mainly those in Russia – experienced unprecedented tree cover loss in 2021, largely driven by fires, according to Global Forest Watch.

If warming in Eastern Siberia continues, forest fires will become not only more frequent but also less predictable, says a study published in 2021.

Floods are another threat to Russians, having caused severe damage in various regions including the Irkutsk region where at least 18 people were killed in 2019.

“These are all visible effects of climate change happening in Russia now. It is finally clear for everyone that the global climate crisis also has highly negative impacts for Russia, with more disasters to come,” Alexey Kokorin, head of the climate and energy programme at WWF-Russia, said in an interview with Reuters.

In 2019 the Russian government approved a National Adaptation Plan until 2022. It lists 30 measures, such as dam building or switching to more drought-resistant crops, as well as crisis preparations including emergency vaccinations or evacuations in case of a disaster.

It says climate change poses risks to public health, endangers permafrost, and increases the likelihood of infections and natural disasters.

However, it also notes the “positive consequences of climate change”. For example, “reducing energy consumption during the heating season, improving the conditions for transporting goods in the Arctic seas and increasing the efficiency of animal husbandry”.

Climate envoy Edelgeriyev has described adaptation in Russia as “unfairly neglected”.